Investigation

Industry Groups Worked to Expand Wisconsin Bill Meant for Small Dairies

Factory Farms•7 min read

Conversations

“The land is producing the most that it has ever produced, but none of that wealth is staying there. So we shouldn’t be shocked that we’re seeing the politics of rage fill that void.”

Words by Grey Moran

President Trump has repeatedly pledged to support farmers and bring down the cost of food, beginning on the campaign trail. “Starting on day one, we will end inflation and make America affordable again, to bring down the prices of all goods,” said Trump at a rally in Bozeman, Montana in August of 2024. Since then, grocery prices have steadily ticked upward. And the high cost of food has recently emerged at the center of another political fight, as the Trump Administration — in a move a federal judge determined to be illegal — suspended the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, blaming the “radical” left.

Yet so far, the Trump Administration has done little to address the roots of this issue: the hyper-consolidation of the food and agriculture industries, according to Austin Frerick, an antitrust researcher from Iowa. In Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, Frerick traces how a handful of major food corporations have become the robber barons of the 21st century, dominating the food system to the detriment of nearly everyone – rural communities, farmworkers, the environment, the animals and everyday consumers.

“What I really came to realize writing this book is I increasingly view rural America as an extraction colony,” Frerick told Sentient. “The land is producing the most that it has ever ever produced, but none of that wealth is staying there. So we shouldn’t be shocked that we’re seeing the politics of rage fill that void.”

In a lively Q&A, Frerick sat down with Sentient to discuss how food industry consolidation has gutted rural communities and deteriorated food quality, how the Trump Administration has further entrenched some of the largest food barons, and what we can all do to build, from the ground-up, a food system that works for more people.

Grey Moran, Sentient:. I’m very excited to talk about your book. I think it’s such an important issue that is massively influential on every aspect of our life. Just to start, if you could just describe what food and agriculture industry consolidation is and why people should care about that?

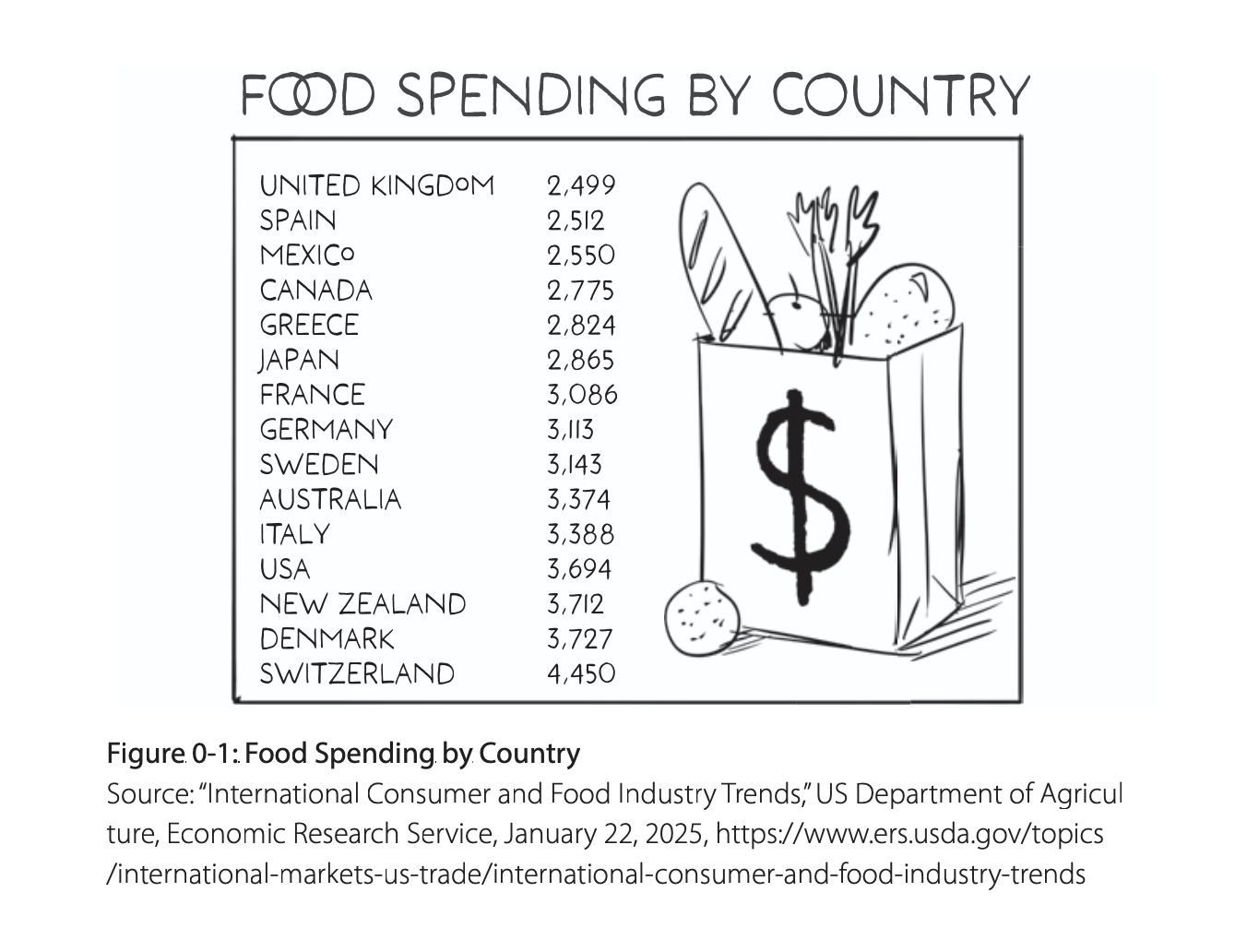

Austin Frerick: Let me start by saying I really do think the most concentrated industry in America is the food industry. This really matters for most Americans because, basically, we’re paying more for lower quality food. One of the first slides I show anymore when I start my talks is what Americans spend on food compared to our other Western peers. We spend more. But we shouldn’t be shocked, because that’s what concentrated markets do. They gouge.

In terms of food quality, inputs matter for meat and dairy. When you put a hog in a metal shed all day, and they just eat corn from a ceiling, they’re not going to taste good. A lot of dairy has shifted to the West. When people think of Vermont, they think of cows. The reality is New Mexico produces three times more dairy than Vermont now because it has massive industrial dairy operations on the east side of the state, near the Texas border. These are just massive cow feedlots in the desert fed corn, and that makes a bad product. That makes a really bad tasting butter. A lot of the produce is bred to be durable, not for taste.

It strips us all of our humanity. It’s just like a cult of efficiency, this race to the bottom, this Excel mind thinking. We’re so much more than a number on a sheet.

GM: “Bred to be durable.” As in animals are bred for a longer shelf life?

AF: Bingo. Everything’s about the shelf life. Because, like, never forget that big boys like to run with big boys. The creation of one robber baron makes other robber barons. It’s what I realized [when researching] Walmart. Walmart wants one company to do 4,000 stores. Walmart doesn’t want a different berry producer for each store. So that’s how a company like Driscoll’s becomes a berry baron, who sells one in three berries. Now Driscoll’s is growing berries on every single continent in the world except Antarctica. They might be coming from Argentina. They might be coming from Morocco. You don’t know where they’re really sourcing from.

When these industrial models are taking hold, the USDA is allowing this race to the bottom. You have Wall Street capital come in to flood the market. There usually is an overproduction of the market. And then that’s when a lot of family farms exit business because they can’t compete against an oversupplied market. Actually, there’s a chart I show on what an average American spent on bacon, adjusted for inflation, before the industrialization of hog. And then when the market collapses, [the price of bacon] collapses. But then after all the family farms leave, and then industrial operations take over, not has the price of bacon returned, it’s even higher than it was before. So what you’re seeing is just monopoly capture.

GM: Looking at the Trump Administration, I’ve had a hard time making sense of what the administration is doing about this issue of food and ag consolidation. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins announced that she would take a “hard look and scrutinize competitive conditions in the agricultural markets.” But then at the same time, the administration has revoked Biden’s order on food industry consolidation and then canceled this other $15 million project to support antitrust enforcement.

AF: This administration is all hat, no cattle. To be frank, the second that Brooke Rollins’s appointment was announced, I just wrote off this administration of doing anything meaningful [on food and agriculture consolidation]. I’m a big believer that personnel is policy, and the story of Brooke Rollins’s career is the story of someone who’s just been a hack for all the oligarchs. Her [previous] job was working at a dark money group [the America First Policy Institute] pushing their interests. So when you come out of that world, I just don’t think you’re not going to find Jesus. You’re not going to care about the family farm when you made your living by doing the bidding of the rich.

I’m happy for her to prove me wrong, but I just to me, this is just another example of hollow words. It’s the burden of the USDA to prove themselves. They need to earn trust back. They need to actually do something, or these markets will keep acting like cartels.

Let’s never forget the current president’s largest inauguration donor was JBS, right? JBS is the largest meat packer in the world. This is saying a lot for this moment in America, but they’re the closest thing we have in corporate America to a criminal organization just because they became a monopolist through bribery. Again, not even campaign contributions. I’m talking like they gave a Manhattan apartment as a bribe to a politician.

One of the first things the Trump Administration did was actually speed up the kill lines, how fast conveyor belts move inside slaughterhouses. This is already one of the most dangerous jobs in America. By speeding it up, you’re making it even more dangerous. So this tells me he prefers to do the bidding of these foreign oligarchs and that he puts them over American workers. Again, prove me wrong. We’re not talking AI. We’re talking hogs. We know what to do here, like we did this a century ago.

GM: What do you mean by “we know what to do here”?

AF: We broke up the meat industry before, like a century ago. The topline rhetoric is breakup, but really it was a consent decree in legal terms, regulations that basically deconstructed the meat industry, coupled with reforms that empowered labor. One little example is that this [consent decree] made it so the meatpackers couldn’t go into retail, so JBS couldn’t own its own meat stores. Fast forward to today, they do – JBS is building retail meat stores across America right now. They’re called Wild Fork. They look like a fake local meat store that’s owned by JBS. No local meat store looks that good. It’s too shiny.

On the flip side, you have Walmart now getting to the beef business. Walmart built a massive beef operation. If we enforce that consent decree, you wouldn’t allow that. Never forget that we don’t need new laws here. It’s just laws that aren’t being enforced.

GM: You write “there’s a set of legal and policy changes driven by radical laissez faire ideology that has resulted in a dramatic concentration of power in the American food industry.” I thought the word choice of radical there was really interesting. Can you highlight some of these policies and what makes them radical?

AF: Part of my choice to use the word “radical” there is to show people the system we have now is actually really radical. It’s radical that one person raises 5 million hogs in Iowa. In the book, I profile eight robber barons but my bigger goal is telling you this is what neoliberalism did to the food system. Neoliberalism, to me, is just laissez-faire. How did we get to this moment where one man raises 5 million hogs?

We have this beautiful anti-monopoly framework going back a century from Justice Louis Brandeis, where basically we want to avoid concentrations of economic power because it corrupts the political system. But starting in the 80s, this man named Robert Bork, most famous to some for being President Reagan’s failed Supreme Court nominee, but he was the one to reinterpret our anti-monopoly laws in America to mean that one company could buy another company if you show that prices go down for consumers. But here’s the thing: you can find anyone to make those numbers. It’s not hard. So now it’s basically a pro-monopoly framework that we’ve essentially been under for the last 40 years.

The other thing that’s really unappreciated in terms of “radical” is how much manure is produced by these industrial animal facilities. Iowa has 25 million hogs. Now hogs defecate three times more than humans. So that’s the manure of 75 million people in Iowa. At the same time too, that regulatory structure has been gutted. So you have the manure [equivalent to the human manure output] of Texas, Illinois and California combined, essentially unregulated.

The second you treat that hog manure like human manure, the economics of that industrial model break. You call this negative externality, where you shift the cost of production and the price is borne by someone else. People in those communities are bearing the price of that, whereas the actual production models aren’t.

These models don’t die overnight. I mean, what happens generally is the economics of the industrial model slowly undermines the economics of the other one. So just the margins get so tight where people eventually go, ‘it’s not worth it.’ And so, you know, one farm will close, the next year, another few [close]. It’s just kinda this thing where at some point you see animals, and at some point you don’t.

GM: What are those externalities? How are local communities that live near factory farms impacted?

AF: What I really came to realize writing this book is I increasingly view rural America as an extraction colony. The land is producing the most that it has ever produced, but none of that wealth is staying there. So we shouldn’t be shocked that we’re seeing the politics of rage fill that void. What used to be like a dignified, middle class job – owning 50 cows on a pasture, taking care of them like any family dairy farm would— has turned into a production model that treats an animal like an Excel sheet line item. It’s incredibly cruel to the animal, but it’s also incredibly cruel to the worker.

I think back to this conversation I had 10 years ago with a high-up executive at the Iowa Farm Bureau. Sometimes economists can say things in a way that’s so devoid of humanity. The future of Iowa, he said, is six towns and a bunch of driverless tractors. First of all, he’s not wrong on these current trajectories. When corn tends to boom up in price, you see a lot of old farm homes go down [in value]. The notion of supply and demand is gone in the agricultural market. It’s always about over-production of grains. A lot of these rural communities are essentially being hollowed out. They’re depreciating assets. No new capital is going into them, and they’re slowly just decaying.

What’s happening in rural America is, as the middle collapses, you’re seeing this extractive model take hold, and like the abusive power dynamics that come with it. The degree of Stockholm Syndrome [in rural communities] has not been appreciated by the coast. People in Brooklyn don’t get how much agriculture production has changed in America and how radical and how new it all is.

Keep in mind, the beauty of a family dairy farm is they’re paying taxes. They send their kids to school. They’re going into town to buy feed, whatever. These barons, a lot of times, they don’t live in the state. They don’t live near their operations. They’re not paying taxes locally. They’re not sending kids to schools. I mean, the whole ecosystem that sustained that middle class farmer has essentially been hollowed out.

I never use the word small family farm. To me, there are either family farms or industrial operators. I don’t even like the term ‘factory farm’ because I don’t want to give them the dignity of being called a farm, like they’re not.

GM: You also talk about how Walmart, the largest grocery retailer in the U.S., is a beneficiary of SNAP.

AF: The origin of SNAP was the New Deal. It was an emergency food program. Just people starving and how to get them food. The modern SNAP program started to take shape in the 60s, then under Kennedy and LBJ. What I realized, researching and writing this chapter is that today SNAP has essentially become a low wage subsidy. Keep in mind, Walmart is the largest employer in America now, as far as private employers go, and it’s the world’s richest family. I mean, fun little fact, they own two NFL teams. But you have people working at Walmart full time, or nearly close to full time, who essentially need to rely on SNAP because they’re not paid enough. So essentially, it’s an indirect subsidy to the world’s richest family because they’re not paying a living wage.

GM: Who would you say are the largest victims of the hyper-consolidation of the food industry?

AF: Undocumented immigrants in rural towns because they’re just so hidden. When they’re abused. It’s slaughterhouse workers in a small town in Iowa. It’s the [farmworkers] working on a dairy farm in Bakersfield. It’s because it’s really, really hard for them to find justice. They’re abused. Most likely they won’t find justice, and their undocumented status allows them to be really exploited. I think that’s who’s bearing the brunt most.

GM: Are there some measures that the Trump administration could take to address ag and food consolidation like right now? Are there laws that could be enforced right now if the Trump administration wanted to address this heads-on?

AF: There’s so much power [to regulate meat industry consolidation]. Actually, the USDA has more antitrust authority over meatpacking than the Federal Trade Commission. So it could do a lot. I mean, it could even do something simple such as why are you giving government contracts to JBS? It’s a lack of political courage. The corporate capture of these governmental systems is why we can’t do common sense, basic-level things.

This administration is putting steroids into this consolidation moment. We’re in a pay-to-play era. A strong case is being made that this is arguably one of the most corrupt modern political presidential administrations in American history. You’re seeing a few things going on here. They’re gutting a lot of the agencies so they fired the people who would normally police these markets, monitor things, step and stop abuses. So we just don’t know what’s going on.

This administration doesn’t want to enforce white collar crimes, so it’s just an open season. People can do whatever, knowing that there’s no recourse. I mean, look at JBS. So after [JBS’s executives] got caught bribing politicians, they were kicked out of their companies. They’re back in charge, and they just listed on the New York Stock Market. I mean, they’re not only firing on all cylinders, they’re bigger and better than they were before.

Reuters reported in September that in JBS’s chicken operations, they have been alleged to use slave labor. I mean, this is just in the DNA of who they are. I just assume everything that results from this consolidation – paying more for less and worker abuse – will just continue to intensify until we have a moment of reckoning.

GM: Along with JBS, are there other major food corporations that you see as being like the biggest beneficiaries of some of Trump’s policies?

AF: I think the meat industry is the biggest beneficiary in the food system, but I also think they’re the most unifying thing for everyone to get around to fix. In Italian there’s this phrase, “politics of the artichoke.” You eat an artichoke one petal at a time, like you take off one opponent at a time. I think reigning in JBS is the most bipartisan thing in America. You can get all these different groups together essentially, like this is just not right. You have ranchers being squeezed. People see that middle schoolers are being employed in these slaughterhouses. People see when they go to buy the beef at the store, the price is unfair. Heck, you have McDonald’s. McDonald’s filed lawsuits [against JBS and other meatpackers] last year for price gouging beef. It says something when McDonald’s is on your side.

You’re even seeing massive consolidation now within that industrial model. What’s happening now is a company like Smithfield doesn’t want to deal with one hog metal shed owner. They want to deal with someone that owns 50, and so even the industrial hog farm owner is being squeezed. I did not expect to have industrial hog farm owners reach out to me but they are. Another issue that has not really been studied or reported is what do you do with these old metal sheds, once that first generation metal shed has run its course. I’ve seen stories here and there of farmers just walking away from a 34 year old metal shed. But underneath most of these metal sheds are these massive manure lagoons.

GM: Since it doesn’t look like the Trump administration will do much to break up food industry concentration, and will probably further it, are there state level laws that aren’t being enforced that could be used to enforce antitrust measures?

AF: If you want to see some really cool stuff right now, look at Minnesota. You have a state Attorney General [Keith Ellison] right now who gets agriculture, who really cares about monopoly, antitrust stuff. So you have him looking into it. You also have a lot of cool farm organizations. I mean, the Minnesota Farmers Union has an-anti monopoly director on staff, Justin Stofferahn, and they’re looking at what cases to bring and what laws apply. This is where I encourage people to put their energies now, just focus on what you can do locally. First of all, it feels good because you can really affect change locally. These things always start there.

When we tell history, we tend to tell it from top-down, when really these changes come from the bottom-up. Everyone thinks Teddy Roosevelt is this big trust buster, when in reality that started decades earlier in Iowa. The first anti-monopoly laws in the world came out of Iowa. Farmers got about grain elevators and railroads so they organized.

I just think we’re at the end of a laissez-faire era. I mean, these laissez faire eras always crash and burn. But for me, it’s what should be next?

Note: this article has been edited for length and clarity.