News

GLP-1 Users Lose Weight, and Their Taste for Meat

Research•3 min read

Feature

A new framework aims to quantify farm animal suffering for better decisions about the way we produce food.

Words by Gaea Cabico

Chicken is the cheapest and most widely consumed meat in the United States, with 9.5 billion birds slaughtered annually. But that low price comes with a hidden toll: chickens bred for rapid growth often endure severe muscle pain, heat stress, lameness and organ failure. Now, researchers have developed a framework for quantifying the good and the bad of what chickens and other farm animals experience. Using this new animal welfare framework, researchers found that a switch to slower-growing breeds would spare chickens from some of the most intense pain and suffering, and with only a relatively small trade-off in cost and greenhouse gas emissions.

Switching from fast-growing to slower-growing breeds could prevent 15 to 100 hours of suffering per bird — at just about $1 more per kilogram of meat (or about 2.2 lbs) — say researchers from the Welfare Footprint Institute, Stockholm Environment Institute and the University of Colorado Boulder in a commentary published in Nature Food on August 18.

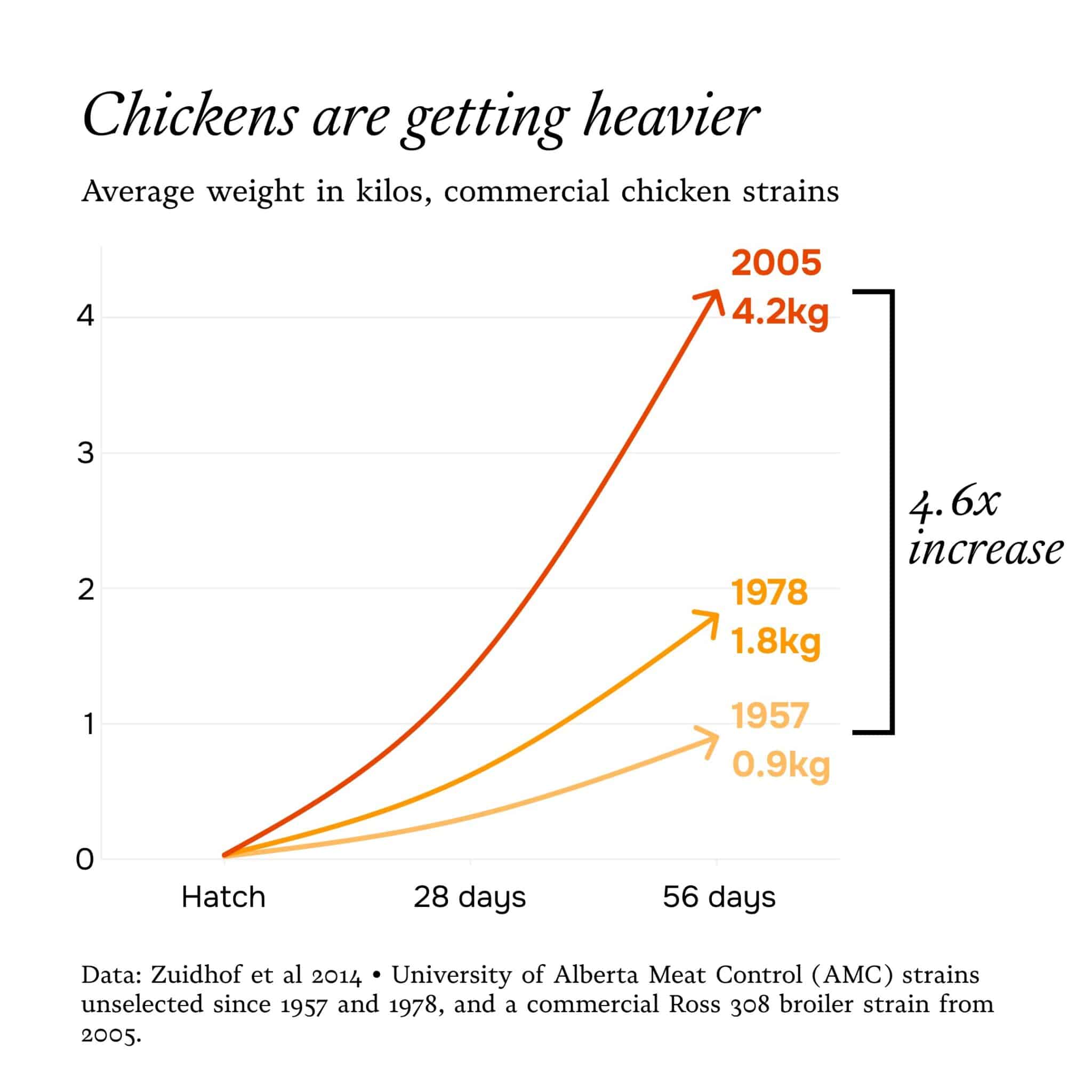

Broiler chickens now grow more than 400 percent faster than they did in 1957, but this rapid growth comes with serious health risks. Researchers say that using slower-growing breeds of chickens can improve welfare, because fast-growing breeds experience more pain due to physical challenges including bone stress, heart disease and heat stress. Nearly all chickens raised for meat in the U.S. are also raised on factory farms, where chickens tend to be overcrowded, compounding their suffering.

The researchers developed a new metric, the Welfare Footprint Framework, to quantify animals’ positive and negative experiences. The new framework can help policymakers, farmers and consumers include animal welfare alongside cost, efficiency and environmental impact in their decisions.

“Just like we measure water use in liters or economic impact in dollars, we need a standard way to measure what animals experience,” Kate Hartcher told Sentient in an email. Hartcher is the study’s corresponding author and a senior researcher and collaborator of the Welfare Footprint Institute, which developed the framework.

Research on food systems tends to focus on economics, health and sustainability, but often leaves out animal welfare. The Welfare Footprint Framework seeks to address this gap by quantifying how much time an animal spends in both negative — referred to as “pain” — and positive — or “pleasure” — states as well as the intensities of those experiences. For pain, this ranges from annoying to excruciating; for pleasure, this ranges from satisfying to blissful.

For example, heat stress causes chickens raised for meat an average of 20 hours of severe pain over their relatively brief lifetimes, researchers say. Some chickens develop ascites, a condition that can lead to a swollen abdomen and heart failure, which adds another 80 hours of severe pain.

Positive experiences for chickens include having comfortable bedding, basking in the sun and foraging, says Matthew Dominguez, U.S. executive director of the advocacy group Compassion in World Farming. The researchers added up all the time chickens spent happy, and counted passive enjoyment as milder than active joy.

For simplicity, the Welfare Footprint Framework left out some of the health problems seen in fast-growing chickens, including muscle abnormalities, skin conditions and infectious diseases. In other words, the framework may even underestimate the welfare benefits of switching to slower-growing breeds.

One goal of the framework is to identify the kinds of changes that would improve animal welfare, Hartcher explains. “This means moving from general welfare aspirations to a precise map of leverage points: it allows us to identify which changes in management, breeding, or technology deliver the largest improvements, and which problems persist even under better systems,” she writes.

Numbers are a simplification of animals’ experiences, and reality is far more complex, cautions Jeff Sebo, director of New York University’s Center for Environmental and Animal Protection, who was not involved in the study. “But if we create and apply these numbers with care, then they can be essential,” he tells Sentient in an email. “Quantification forces us to acknowledge that our choices can add up to vast amounts of happiness or suffering.”

The Nature Food commentary also examined the environmental impacts of switching to a slower-growing breed. The switch would increase emissions by about 1 kilogram of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilogram of chicken.

“Even when scaled globally, the emissions increase from slower-growing breeds remains small in context, especially compared to the scale and severity of pain avoided,” Hartcher said. She added that when lower mortality, fewer carcass downgrades — when chickens are found at slaughter to be damaged, diseased or otherwise unfit for full market value — and lower antibiotic use are factored in, “the environmental difference shrinks even more, and in some cases may even disappear.”

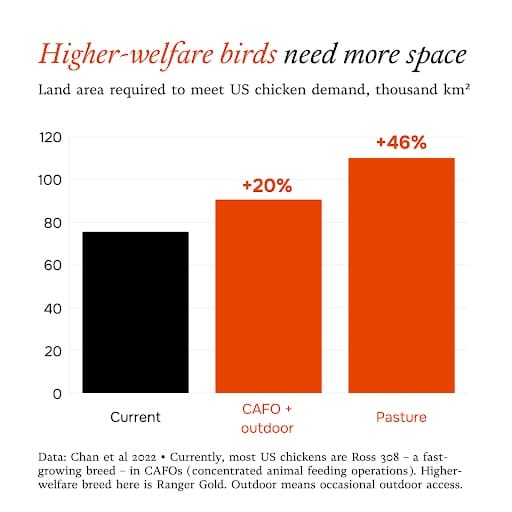

Raising slower-growing breeds also requires more land. Assuming Americans continue to eat the same amount of chicken, chicken farms would need more land to raise more birds to satisfy that demand.

The reason land has such a huge climate impact (as big an impact as cattle burps) is that when forests or other uncultivated landscapes are deforested and converted to farmland, the land releases the carbon dioxide it was storing — and on top of that, the land loses the ability to store carbon in the future (unless you rewild it again). Researchers call this mega-hit to climate a “carbon opportunity cost.”

The type of farm also affects the calculation. A 2022 study found that raising slower-growing breeds of chicken in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), commonly known as factory farms, would require 20 to 31 percent more land than typical breeds, while pasture-based systems, which are better for welfare, would need much more land — 44 to 60 percent.

There are compromises: raising slower-growing chickens with occasional outdoor access is a middle ground that would require only a small amount of extra land compared with raising them entirely in CAFOs.

Some animal welfare advocates see the Welfare Footprint Framework as a tool for improving negotiations with food companies. “When we tell executives at Subway, Chipotle or Kroger that they can prevent” 15-100 hours of pain per chicken “for roughly the same cost as carbon offsets,” Dominguez told Sentient in an email, “it shifts the conversation from ethics to evidence-based business decisions.”

Translating something abstract like pain into numbers might also influence shoppers. “For consumers, that might mean choosing products that demonstrably reduce negative experiences for animals,” Hartcher says.

And while the framework does not recommend a particular course of action, Hartcher hopes it will allow policymakers to “evaluate reforms and understand the ethical cost of different food system trajectories.”

“Whether this leads to higher-welfare production, stricter regulation, or broader shifts in how we use animals is ultimately a societal and political choice,” Hartcher adds, “but one that can now be made with clarity rather than guesswork.”