Explainer

How Livestock Farming Affects Climate Change, Explained

Climate•7 min read

Explainer

It all comes down to burps and land.

Words by Björn Ólafsson

It’s no longer news that eating meat is bad for the planet. Study after study after study confirms how much pollution comes from the food system — emissions from meat and dairy make up around 14 percent of all global emissions, with 57 percent of food-related emissions coming just from meat.

Not only that, it’s impossible to reach the climate goals of the Paris Agreement — staying under 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming — without tackling the problem of how much beef we as a planet consume. It cannot be done.

Yet somehow consumers aren’t getting the message. A January 2023 survey from Purdue researchers found the belief that eating less meat is good for the environment is now at an “all-time low,” with only 46 percent of respondents in agreement. Perhaps what’s needed is a clear explanation of why exactly beef is bad for the environment. There are a few reasons why, in fact, but in the simplest of terms, it all comes down to burps and land.

Cows belong to a category of animals called ‘ruminants.’ Under the suborder Ruminantia, this category also includes creatures like goats, sheep, giraffes, deer and buffalo. Ruminants eat grass, have hooves and — here’s the important point for climate emissions — have four stomachs in which to digest their food.

Inside these stomachs is where the magic happens. The grass goes into the rumen, the first stomach, where it ferments the food to begin breaking it down. After a while, the cow partially regurgitates the food, now called cud, and then chews it even more, which hastens the cellular breakdown. The food then flows into the other three stomachs where it is digested through microorganisms.

This is great news for the cow — the process of enteric fermentation enables ruminants to eat all sorts of roughage that humans couldn’t ever (or at least wouldn’t ever want to) digest. But, here’s the kicker, the process also creates a harmful byproduct called methane.

Methane is an exceptionally potent greenhouse gas, having 80 times the warming power in the first twenty years of its release into the atmosphere as compared to carbon dioxide. Methane disperses or breaks down faster than carbon dioxide, but it also does more damage while it’s here.

Cows, because of their distinct biology, produce a lot of this dangerous methane when they digest their food. A single cow can produce up to 500 liters of methane a day. Today, the ranching industry breeds as many as 1.5 billion cows per year, and methane emissions from cattle are a real climate problem. In fact, methane is the second most abundant greenhouse gas found in the atmosphere, and 40 percent of all methane comes from agricultural sources, with livestock production directly responsible for 32 percent.

The good news is that the properties of methane — its relatively short span of existence in the atmosphere as compared to CO2 — also offer up a powerful opportunity for climate action. If we drastically reduce our methane emissions, we will start seeing the benefits in terms of drawing down emissions right away, and that buys us time to bring down more stubborn areas of climate pollution.

Before we dive into how to reduce methane emissions, it’s important to understand the other part of beef farming that drives climate pollution: land use.

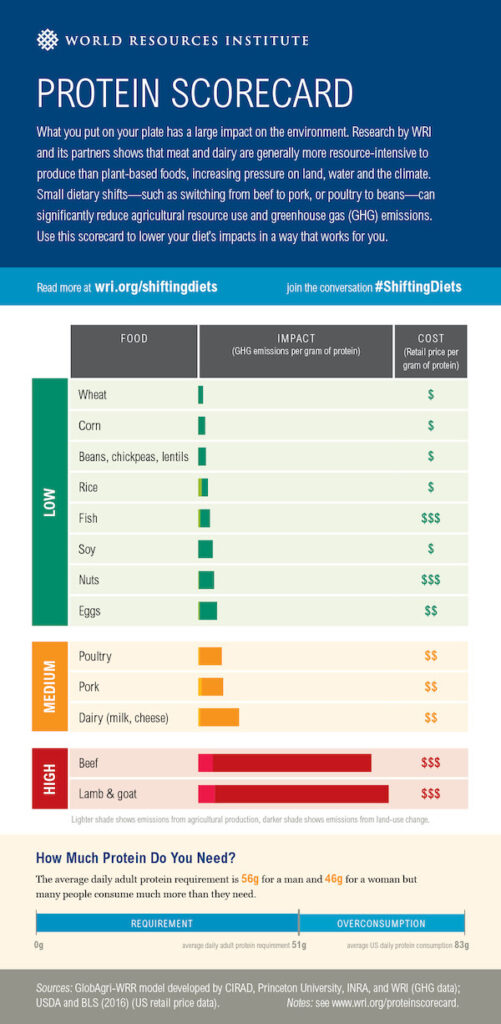

A whopping 77 percent of global farmland goes to raise livestock. Per gram of protein, beef and lamb require more land than any other protein to produce, according to analysis from Our World in Data.

The problem is we don’t have unlimited farmland, but we’re acting like we do. As the Earth’s population goes up, farmers end up expanding their operations in order to produce more food. Between 2000 and 2019, global farmland expanded by 9 percent, according to reporting in Science magazine. And when that expansion takes place in tropical rainforests and grasslands — which is exactly where it’s happening most often — the climate cost is especially painful.

Let’s dig into why. Wild landscapes like the Chiquitano rainforest and the Cerrado in Brazil are important carbon storage reservoirs, places where the earth sequesters or stores carbon, keeping it out of the atmosphere. In other words, these wild landscapes are kind of like built-in climate solutions — that’s why they’re often called nature-based climate solutions.

So, when we deforest a wild landscape, there are a couple of emissions to consider. First, the land releases the carbon that it was storing but there’s another loss too. Every year after that, that piece of deforested land has now lost its carbon-storing abilities.

Big picture: emissions keep going up but, thanks to that deforestation, we can no longer count on the carbon-storing offset of the land we’ve now turned into a farm or a ranch. Called the carbon opportunity cost by researchers, that loss makes the emissions associated with beef even higher.

On the other hand, the potential to reverse that land loss is also pretty massive. If the whole world switched from animal-based agriculture to plant-based agriculture, we would get back more than 3 billion hectares, yes, billion with a b. To put that number into perspective, that’s the size of Brazil. And Mexico. And Canada. And the entire United States, combined.

Now, due to the different biologies and geologies, not all of this land could be converted into plant-based agriculture suitable for humans, and that’s the point. Only a small portion would be needed to grow food for humans. The rest can be returned to nature to store carbon — not to mention serve as much-needed habitat for biodiverse species. According to a 2022 study, if wealthy nations switched from animal-based to plant-based, they’d reduce their emissions by over 60 percent and sequester almost 100 gigatons of carbon emissions.

There is more than just climate emissions to consider. Ranching increases the risk and likelihood of the next pandemic, abuses antibiotics, kills 300 million cows globally per year and causes physical and emotional trauma for workers. Not to mention that its inherent inefficiency makes it prone to inflation and supply chain breakdowns during crises like war and pandemics.

All of these impacts are why it’s so important to boost public understanding of the climate impacts of meat. One of the most powerful forms of climate action is reducing meat consumption, especially red meat, in favor of a plant-rich diet. According to analysis from Project Drawdown, this type of dietary shift along with curbing food waste could reduce 12.4 percent of global emissions.

This piece has been updated.