Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Investigation

I hopped aboard a tuna tour to investigate what it takes to confine these majestic apex predators.

Words by Rachael Adams

It’s 10 a.m. at the sunny Spanish marina in Ametlla de Mar, Tarragona. A banner that reads “Tuna tour – Possibly one of the best adventures of your life” stands square on the jetty in front of a slick white catamaran, ready to take tourists to scuba dive with “wild Atlantic bluefin tuna in their own habitat,” as the tour’s site explains. I’m asked to grin for a photo as I climb aboard to the party song, “That’s the Way I Like It.” We’re about to head three miles offshore, just enough time to watch the tour company’s promotional video.

The Balfegó tuna company farms wild-caught Atlantic bluefin tuna in cages off the east coast of Spain. Unlike tinned tuna, which are made of smaller species, Atlantic bluefin tuna are massive creatures, fattened up by Balfegó on mackerel and sardines to be harvested on demand whenever an order comes through. Most of the fish is exported to Japan, where sushi and sashimi, expensive treats before the 1960s, are now a part of the daily diet. Since Japanese wild tuna stocks have been exhausted for several decades, chefs rely on farmed tuna, largely imported from Europe.

Nearly all of the Mediterranean-caught bluefin tuna now go to fattening farms located mostly in Italy, Malta, Croatia, Spain and Turkey. In 2023, these countries collectively caged 22,754 tons of tuna. Four farms in Malta alone account for a third of the tuna caught in Europe. Since consumer demand for tuna continues to rise amid diminished wild stocks, Atlantic bluefin tuna are an extremely valuable product: in 2019, sushi chef Kiyoshi Kimura famously paid a record $3.1 million for one in Tokyo’s fish market. In other words, tuna farming is a very lucrative enterprise.

Balfegó, which won a prize from the Catalonian government for sustainable tourism, also offers diving tours on their farms, which they portray as sustainable, traceable and transparent. Here, visitors feed the tuna and dive with them, getting a rare glimpse of how these fish live in captivity — a far cry from “their own habitat,” despite the company’s marketing claims.

As we head out and the short film plays, an announcer explains how fishing boats catch wild tuna off the southwest of Ibiza, in the Western Mediterranean Sea. In 2022 their fleet of 30 boats caught 2,458 tons of tuna, which made up over a quarter of the quota for all the countries in the Mediterranean basin.

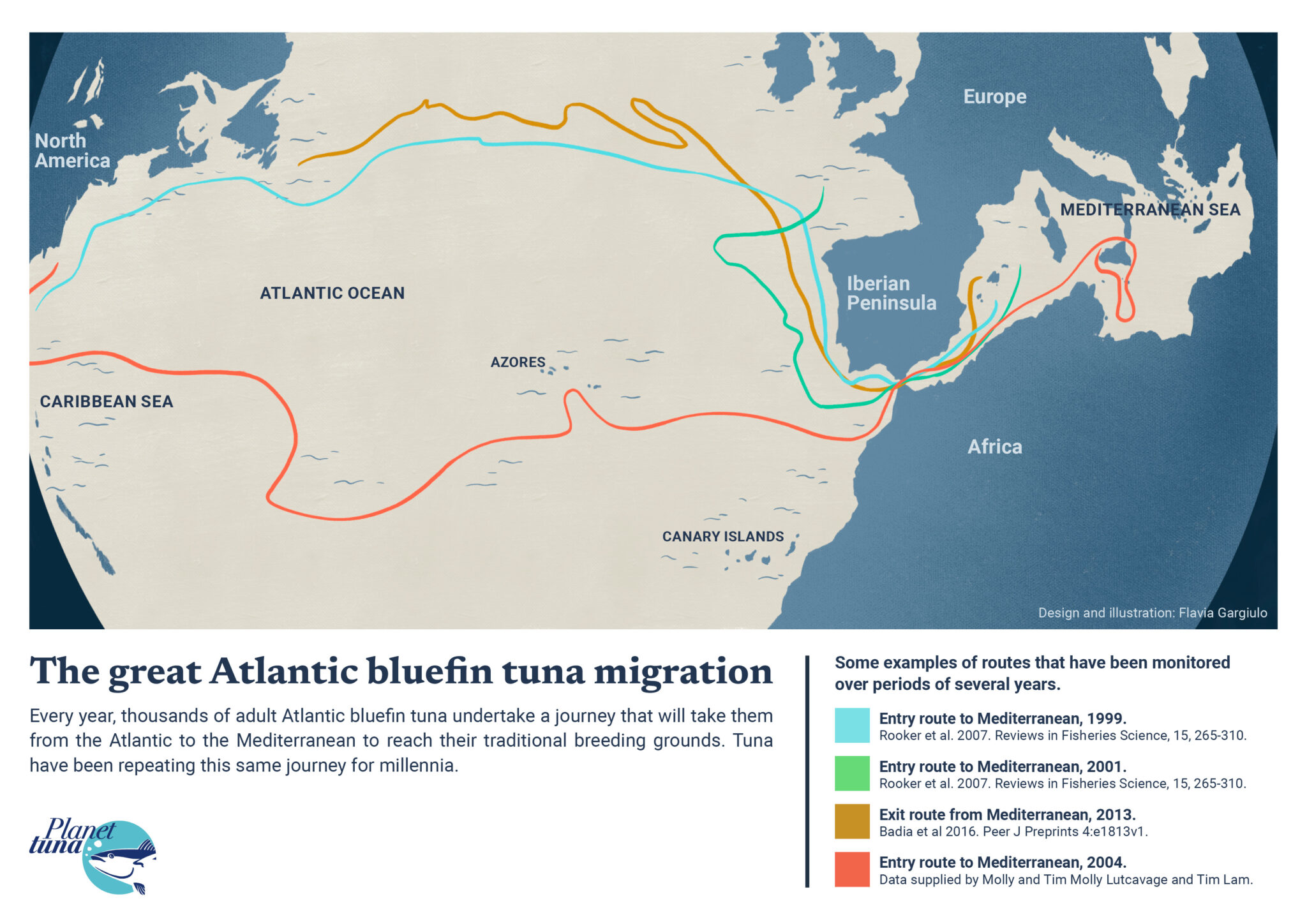

The fish migrate to the Mediterranean from the eastern Atlantic Ocean to breed. During the five-week fishing expedition, fishers use large nets to encircle the young tuna shoals, sort them into different nets for transport and very slowly tow them back to the farm for fattening in Tarragona. The process takes weeks, during which time some fish will likely die en route to the farms and be discarded before fisheries observers can count them. For those fish who do make it, the narrator says, they’ll “live a natural life.”

The company says it only captures fish that are at least 66 pounds, which means they are usually four years old and sexually mature. At that stage, the fish should have spawned at least once, to allow whatever fish that have been taken to be replenished, ensuring the continuity of the species.

The fishing expedition is supervised by an observer from the The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, the regional management body. Adhering to the conservation group’s regulations has earned Balfegó a certificate of sustainability. Yet tuna populations continue to dwindle. Despite progress on boosting the fish’s numbers, some environmental groups say they’re concerned that wild stocks may not have fully recovered. One such group based in the UK, The Marine Conservation Society, lists farmed Atlantic bluefin tuna as a fish to avoid, because the industry relies on catching young tuna and feeding them vast amounts of fresh fish.

The 14-minute video details the entire process, from the fishing expedition to the fattening, harvesting and packaging for sale. It’s not clear how the fishermen determine that the fish have reached the right size before catching them, nor does the film show how undersized fish are removed from the nets if necessary. Sentient contacted Balfegó to ask how fishermen could be sure each fish weighed 66 pounds before catching it in the purse seine net, but received no response.

Balfegó also claims to be the only farm in the world to tag each fish with a QR code documenting its voyage from net to fork. Yet the mackerel and sardines that make up these farmed tuna’s diet are not traced. What species combination each farm chooses as feed is considered proprietary and is not usually made public, but typically feed fish for tuna farms is imported from as far away as Norway, Mauretania and South America to ensure a year-round food supply of an otherwise seasonally available fish. Balfego did not respond to Sentient’s request for comment on the traceability of its feed fish.

The tour participants are busy preparing their cameras and do not seem interested in the video. We near the spot in the water where the farm is located and quickly don our wetsuits. The guide calls us outside for the brief as we moor alongside one of the dozens of cages. Seagulls perch on the buoys holding the nets.

As we bob in the breeze, our guide explains that the cages holding the fish are circular nets, 165 feet in diameter and 100 feet deep, housing between 300 and 400 fish each. The fish are mostly found in the first 50 feet of water so we won’t dive below that. This means each fish has approximately 150 square meters in which to live, which is a lot when compared to other farmed fish — but not for wild tuna that typically migrate across entire oceans repeatedly throughout their lifetime. These predators are designed to travel fast and far: after spawning in the Western Mediterranean, adults return to the Atlantic, a roundtrip journey covering thousands of miles.

The farmed tuna caught by Balfegó are confined in nets for at least two years, fattened on a diet of mackerel and sardines. The guide is carrying some in a net bag for us to feed to them. These fish are tuna’s preferred prey, but they are also an oily fish that helps them gain weight and provide the desired fatty taste to consumers.

Farmed tuna eat a lot more than wild ones, whereas wild tuna tend to hunt for a much wider variety of prey. What these giant fish catch will depend on their age, where they are and what is available at that time of year. Tuna mostly hunt from the surface to 650 feet deep, sometimes in coordinated packs. A study on Atlantic bluefin in the Mediterranean found the tuna’s stomachs were mostly full of deep-dwelling lantern fish, Hygophum benoiti, and shortfin squid, Illex coindetii. The rest of their diet was made up of shrimp, eels, garpike and bream. Removing large amounts of both wild tuna and wild-caught feed-fish can prevent these fishes from providing necessary ecosystem services, like stabilizing natural food webs.

Tuna have an internal counter-current heating system that keeps their core body temperature higher than that of the surrounding waters. This is useful for hunting at speed and provides an advantage when tuna are in the cold northern Atlantic waters. However, it also requires tuna to eat a lot of fish to maintain this system, even for their large size. To produce 1 kilo of farmed tuna requires 15 kilos of feed fish, which is why some researchers consider the Atlantic bluefin one of the least sustainable fishes to farm. Currently, over a third of the world’s wild fish are now caught for feeding intensively farmed fish, which is part of why a shift to aquaculture has not relieved pressure on many wild fish populations.

Back on the boat, we get our turn to slip into the water. The current on the surface is strong. We are warned to hold onto the edge of the net and stay away from the central feeding station, an off-limits circular area surrounded by buoys. As we descend, we’re surrounded by the magnificent bluefin. These are the largest of the tuna family, reaching 14 feet in length and naturally living for up to 35 years. Other than the net walls, there are no visual references, so we stay close to our guide to avoid becoming disoriented.

Immense bodies flash past within barely a few feet of us. I can see gaping mouths and the whites of their curious eyes rolling back to watch us as they swim past, between us and the net walls encasing us all. These fish are amongst the fastest in the sea, built for powerful bursts of speed. Everything about their bodies attests to their predatory nature: the large eyes, the stiff forked fins, the horizontal keels and sharp yellow finlets along the tail that cut through the water. The pectoral fins fold away into slits to further reduce drag.

We dive for 45 minutes, holding the dead sardines at arm’s length to then let it go. Tuna burst upwards from underneath us to grab the fish. Cameras click incessantly. As with sharks, tuna need to swim constantly in order to breathe. Yet instead of crossing vast oceans, these farmed tuna swim in unnatural, clockwise circles, and they do so for years — until they’re fat enough to shoot.

Once an order is placed by a client — often a restaurant or sushi chef in Japan — the tuna is shot with an explosive harpoon by a freediving marksman who dives into the shoal of fish. They take 40 to 50 fish, up to three times a week, depending on demand. The sea turns red with blood as the fish are hoisted from the water, then packaged and “eaten fresh in a few hours on the other side of the planet.” Flying fresh, perishable produce approximately 6,000 miles from Spain to Japan emits around 50 times more greenhouse gas than transporting the same food by boat. While transportation emissions in general only account for around six percent of food-related climate pollution, express air freight does drive up the climate impact of some food choices. And for tuna, there are other consequences stemming from feeding small wild fish to these massive creatures — depleting ecosystems and what has been a traditional food source for some populations in the global south.

We surface from the dive and are offered sashimi and a glass of champagne. The divers take each other’s details and promise to send the pictures. I walk down the gangway, having experienced not “possibly one of the best adventures of my life,” as the promotional materials told me, but a sense of fury at how these once-wild, majestic hunters and apex predators at the top of the ocean food chain now swim in circles until they are fat enough to be eaten in expensive restaurants on the other side of the world. Despite the certifications, tuna farm operations, like Balfego, are one of the least sustainable types of aquaculture.

The bottom line: the company has taken what is the fisheries-equivalent of an intensive pig farm and turned it into an eco-adventure for conscious consumers.