Explainer

How Overconsumption Affects the Environment and Health, Explained

Climate•12 min read

Fact Check

Analyses of top podcasts show a trend of climate change denial and misinformation.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

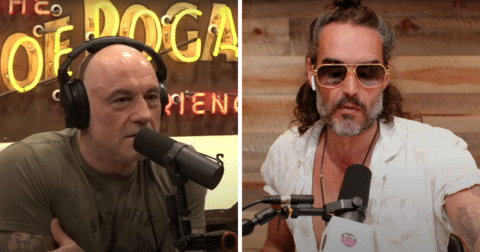

Remember last November, when Elon Musk joined Joe Rogan on his podcast, and the two dismissed meat production as “irrelevant” to the climate crisis? Or last December, when fellow podcaster Russell Brand, once a committed vegan for ethical and environmental reasons, posted about eating steak at Mar-a-Lago with President-elect Trump? New research from Yale finds that the leading podcasters are increasingly serving up misinformation about climate change and the impact of eating meat, with a side of charisma.

“Of the 10 most popular online shows, eight have spread false or misleading information about climate change,” the Yale Climate Connections analysis found. It also revealed that rather than outright denying climate change, today’s most influential media personalities now push subtler, more insidious narratives — arguing that climate solutions don’t work, that global warming is beneficial or that environmental policies are just tools for government overreach. According to the Center for Countering Digital Hate, these “new denial” messages made up 70 percent of climate misinformation on YouTube in 2023, up from 35 percent in 2018.

Misinformation has consequences for climate action, especially around the role dietary change can play to bring down emissions. Eating less meat is one of the most powerful forms of individual climate action, according to Project Drawdown. Yet polling has shown that 74 percent of Americans believe eating less meat would have little or no effect on emissions, when the opposite is true.

The popularity of podcasts is growing, as audiences look to the medium and their influential hosts for important information, including news. According to Pew Research, nearly half of all Americans surveyed (49 percent) tuned into a podcast in 2022. And among those listeners, more than one in three (36 percent) stated they made a lifestyle change, like adjusting their diet, based on something they heard; 28 percent said they bought something promoted or discussed on a podcast.

Elisa Tattersall Wallin, a researcher at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science, University of Borås, who has studied podcasts and climate information, tells Sentient that the draw of podcasts may be due in part to a perceived authenticity. “Studies show that podcast hosts often talk in a very informal and personable style,” she says, “and so they’re perceived as authentic, and you believe someone who’s authentic.” This can be in stark contrast to professional journalists on television or radio news, “who might speak in a more formal tone.”

“Many podcasts are intended to, first and foremost, provide a source of entertainment to their listeners,” John Kotcher, director of research at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, told Sentient in an email. “The goal of providing news and public affairs content may be secondary, if it is a goal at all.”

Kotcher also adds that “podcasters may not place the same degree of scrutiny into researching prospective guests’ climate expertise and credibility when booking them, or into fact-checking the statements guests make once they’re on their show.” Some podcasts may simply not have the resources to conduct this kind of background research or fact-checking, he adds, “to ensure that quality information is being presented to their listeners.”

In her research of climate change topics discussed on Spotify and Apple Podcasts, and through podcast search engine Listen Notes, Tattersall Wallin observed two dominant types of shows: ones that she calls “factual channels,” typically hosted by journalists, academics or in one case a comedian with a science background. And the others: right-leaning “obstruction channels” that spread misinformation.

Factual podcasts and online shows focus on education, science and solutions, she writes, while obstruction channels — like those from The Epoch Times or the Heartland Institute — often push conspiracy theories and deny climate science. These misleading channels will often use emotionally charged titles, such as: “Rise of ‘Scientism’ and the ‘Junk’ Climate Models Used by Government to Take Farmers’ Land,” and avoid clear categorization. “The factual channels are typically marked up with several categories [on Spotify], the most common being ‘Science,’ ‘Society,’ ‘Educational,’ and ‘Culture,”’ writes Tattersall Wallin. “The climate obstruction channels are less likely to have any categories attached to them.” Avoiding categorization helps creators evade moderation by the platform.

The recent research from Yale’s Climate Connection shows a similar trend. The analysis builds on recent work by Media Matters for America, a journalism watchdog group that found right-leaning influencers now hold a dominant presence across digital media platforms, including podcasts and livestreams. It reveals that climate misinformation in particular is thriving on podcasts and digital platforms, with eight of the ten most popular online shows having shared false or misleading climate content.

“Much of the climate-related misinformation spread on these shows follows a revamped playbook of climate denial that focuses on denying the effectiveness of solutions and argues that climate change is beneficial,” according to the report. “Influencers Jordan Peterson and Charlie Kirk also presented those concerned about climate change as adherents of a ‘pseudo-religion.’”

Some of these platforms are also backed by wealthy right-wing donors, all while presenting themselves as independent truth-tellers. For example, the Daily Wire, cofounded by Ben Shapiro, is reportedly bankrolled by Texas fracking billionaire brothers Dan and Farris Wilks.

Some are even backed by foreign agents. As Sentient reported in 2024, The U.S. Department of Justice indicted two employees of the Russian state-backed outlet RT (formerly Russia Today) last year, for hiring Tenet Media, an online content creation firm in the U.S. The company pushed a wide range of climate misinformation via influencers and podcasters, and downplayed the environmental impact of meat production as part of a broader effort to undermine public trust in climate science, and hinder climate action.

For Tattersall Wallin, the Facts Matter podcast by Epoch Times stands out as particularly lacking in transparency. The show’s tagline is “no spin, no favorites. We give you the facts—you decide the rest.” She says the show claims it’s “free from the influence of any religion or organization or political party.” But then, “if you sort of just scratch the surface, they were not at all free. They’ve supported Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen, and spread a lot of climate change misinformation, and are very obviously climate deniers. And so, can you then claim that you are free from religious or political affiliation or influence?”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the climate impact of meat is also often misrepresented on podcasts.

For example, on The Joe Rogan Experience, conversations about meat and climate change have frequently leaned into skepticism and misinformation. In a 2024 episode with Elon Musk, the two dismissed the idea that eating less meat could help the planet, with Musk calling the connection “irrelevant” — a statement that flatly contradicts climate science.

Similar narratives have surfaced in earlier episodes with guests like Steven E. Koonin and Mark Sisson, and more recently wellness influencer Gary Brecka, with Rogan questioning the the evidence that meat-heavy diets are fueling climate pollution. Across these episodes, Rogan’s platform has amplified a narrative that downplays the environmental toll of meat production, ignoring the robust body of evidence linking industrial animal agriculture to rising emissions, deforestation and ecological collapse.

And while celebrity podcaster Russell Brand once emphasized the environmental harms of meat consumption, his more recent content often questions mainstream climate science, and downplays the role of animal agriculture in global emissions. Years ago, Brand hosted Kip Andersen, co-director of the vegan documentaries “Cowspiracy” and “What the Health,” on his podcast Under the Skin. But more recently, he’s appeared alongside carnivore diet-promoters Mikhaila and Jordan Peterson, and has platformed a well-known climate change denialist, Danish political scientist Bjørn Lomborg.

While some popular podcasts may be rife with climate misinformation, Kotcher notes that as a whole, podcasts aren’t all bad. In fact, they can offer great opportunities for deeper dives into complicated climate topics due to their extended length, “which allows for a level of audience learning that’s simply impossible to achieve in a 5-minute segment on radio or television, or a short news article.”

In order to better navigate podcasts and social media, media literacy is the key to discerning credible content from misinformation. (For more on this, see Sentient’s guide on How to Spot Misinformation and Bias About Climate and Food in the News.)

Some of the most popular podcasts are enabling the spread of misinformation about climate action. Yale’s finding that eight of the top-10 online shows are pushing climate misinformation underscores the need for stronger media literacy.

Podcasts can be part of that equation. For Kotcher, there’s no reason to quit the medium altogether, as podcasts “can be fantastic sources of information on climate change.” The key is who you’re listening to. For quality podcasts on this topic, he suggests Shift Key from Heatmap News, A Matter of Degrees by Leah Stokes and Katherine Wilkinson and Volts by David Roberts.