News

Minnesota Asks the Public Whether Groundwater Rule Is Enough to Curb Farm Fertilizer Pollution, Following Lawsuit

Climate•7 min read

Feature

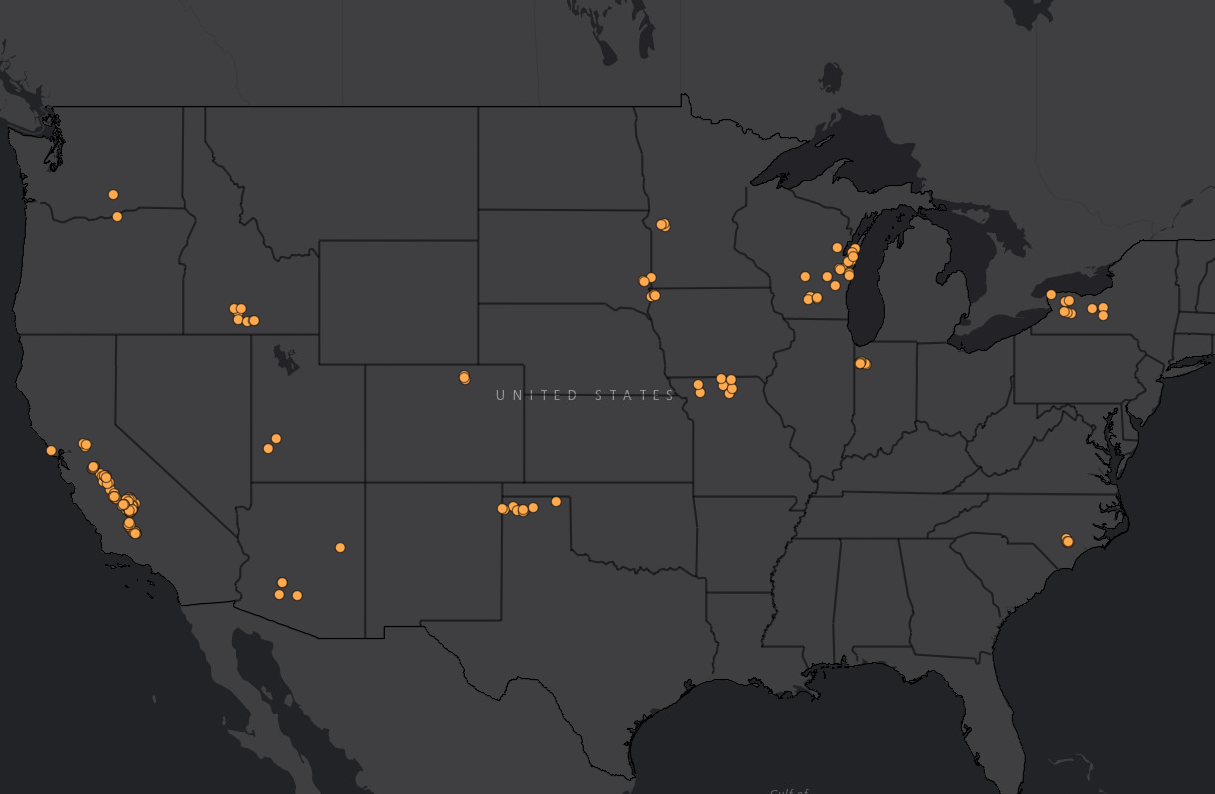

Anaerobic digesters now stretch across the U.S. to supply California’s LCFS market, raising environmental concerns beyond state lines.

Words by Nina B. Elkadi

From coast to coast, large-scale anaerobic digester facilities, designed to produce biogas for processing into a usable low-carbon fuel, are popping up near concentrated animal feeding operations, otherwise known as CAFOs. A new interactive map from non-profit advocacy group Food & Water Watch illustrates the nationwide expansion of digester facilities earning money through California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) program. Their analysis shows that 45% are located outside California. After the Golden State, Wisconsin has the most digesters, growing from zero participating facilities in 2019 to 20 today.

California’s policy is intended to decrease the carbon intensity of the state’s transportation fuel supply through what are meant to be lower-carbon alternatives, like biomethane. Energy companies can earn or buy financial credits for producing these fuels. Anaerobic digesters break down manure and organic matter to produce biogas, which is processed into renewable natural gas or biomethane. Digesters are promoted as a climate-friendly way to offset the agricultural industry’s emissions, but they may come with significant trade-offs.

New research suggests that the expansion of methane digester projects to support an LCFS-driven market does not actually reduce global methane emissions. Some advocacy groups, like Friends of the Earth, raise concerns that the program’s fiscal incentives perpetuate the methane problem by rewarding CAFOs for expanding herds and producing more manure.

“We have out-of-state actors supposedly mitigating their methane emissions and then selling that to in-state actors who get to emit more,” argues Food & Water Watch staff attorney Tyler Lobdell. “They can pollute their neighborhoods with wanton abandon. California does not care. California is not looking.”

The value of LCFS credits issued since 2013 is over $22.1 billion, a number that inflates how much fossil fuel companies have actually reduced their carbon impact. As the industry is shifting these carbon offsets to other states, the environmental cost of biogas digester expansion reaches far beyond fossil fuel balance books.

California’s Incentives Change the Country

Anaerobic digesters have also rapidly expanded as a result of California’s policies, Food & Water Watch argues in an analysis of the data. Over the past six years, since 2019, the number of states with participating operations has grown from three (California, Missouri and Indiana) to 16. Since California’s LCFS launch in 2011, the total number of manure-based digesters has increased from 145 to 394.

The very landscape of farm country is changed by these operations. The herd expansion needed to meet biogas demand leads to more manure and increased air pollution and water pollution. In states with prolific industrial animal agriculture operations, like Wisconsin, residents are facing a drinking water crisis due to pollutants in their well water, with no clear answers from the state on how to remedy the situation.

“This is not agriculture. This is not factory farming. This is a whole new industry, and it’s complicated as hell,” Lobdell says. He describes how complex it is to maintain a biogas digester, including the physical realities of operating an anaerobic digester lagoon without leaks and other issues. Digester facilities also require pipelines and other infrastructure to transport the processed biogas.

Many factory farms that operate digester projects do not actually own the equipment. Digester projects are often funded through government subsidies and public programs, and agriculture law and policy experts say the industry is attracting more private investors. A $41.5 million digester project in Gillett, Wisconsin, was financed through tax-exempt municipal bonds funded by private equity companies. In June 2025, the project missed its $1.7 million principal payment, raising questions about the fiscal feasibility of these developments.

A Win for the Fossil Fuel Industry

California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard was implemented to push the fossil fuel industry to reduce its climate impact by producing low-carbon and renewable alternatives. In theory, manure from factory farms provides a potentially limitless supply for credits, Lobdell argues, ultimately incentivizing the companies to keep purchasing credits rather than changing their practices.

“If I’m a fossil fuel company, I see a pretty cheap and bottomless reserve of mitigation,” he says. “It’s a very, very beneficial system for the fossil fuel industry.”

Last year, the American Biogas Council, a pro-biogas trade association, voiced its support for the expansion of the LCFS, writing that the program has “proven essential in driving down greenhouse gas emissions, promoting cleaner fuel adoption, and supporting the state’s ambitious climate goals.”

Reporting published by the California Air Resources Board in October suggests biomethane generated credits valued at just over 2 million metric tons. However, a new research analysis suggests that the carbon offset of LCFS manure-digester participants like CAFOs is distorted by only accounting for emissions from the manure lagoons and not the entire farm.

The authors also suggest that manure-based biogas accounts for 21% of all LCFS credits while supplying less than 1% of transportation energy.

Patrick Serfass, Executive Director of the American Biogas Council, tells Sentient that this data confirms that the LCFS is working and “incentivizing the private sector to innovate and decarbonize the transportation sector itself. And that’s a wonderful thing.”

Defensores del Valle Central para el Aire y Agua Límpio, Food & Water Watch and the Animal Legal Defense Fund are currently suing the California Air Resources Board for not fully analyzing or mitigating the harms that could be caused by the LCFS amendments, which allowed for manure-based biogas.

Other options to control the manure problem exist, but through subsidies and tax credits, digesters have become a preferred route for many U.S. policymakers to point to progress on the manure problem, and this new map demonstrates just how far-reaching these operations are.

“There is no end game here other than factory farms being perpetual methane production facilities,” Lobdell says. “And that is such an asinine approach to climate mitigation.”