News

Grasslands and Wetlands Are Being Gobbled Up By Agriculture, Mostly Livestock

Research•4 min read

Conversations

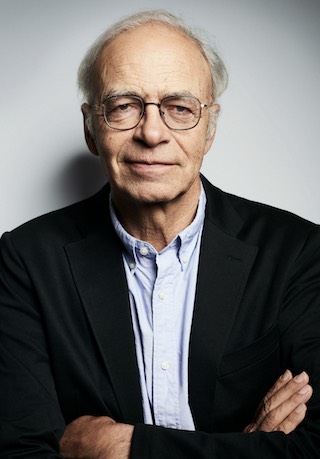

Philosopher Peter Singer has been highly influential in shaping the ethical foundation for animal protection, in addition to his long career in ethics, especially utilitarianism.

Words by Mikko Jarvenpaa

What are our duties towards others, especially those who are less fortunate than us? Who are such others, and how can we do the most good for them? Philosopher Peter Singer has worked on such questions for decades. Singer is one of the most influential ethicists in the world and has gained this highly visible and sometimes controversial standing due to his focus on two major areas: the lives of non-human animals, and questions concerning human lives at the margins of human experience.

Since the first publication of his book Animal Liberation in 1975, Singer has been a key thinker and leader in the animal protection movement. Multiple editions of his book have been published in the last 45 years. Outside of academic philosophy, Singer’s work has also been instrumental in informing and championing effective altruism. Peter Singer serves as the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

Sentient Media’s founder Mikko Järvenpää interviewed Peter Singer in April of 2020. What follows is a lightly edited version of their conversation. In this interview we focus on non-human animals, as should be expected of Sentient Media, but we also touch on human topics due to the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic that is ongoing as of this writing.

Mikko Järvenpää: It’s difficult to start any conversation these days without some reference to the current situation with the pandemic. So let’s start there. How are you?

Peter Singer: I’m fine, thank you. And I hope the same goes for you?

MJ: Yes, the same over here, thank you. You’ve written about the response to the COVID-19 pandemic recently. Is there anything that has surprised you about our response to the crisis such as it is now?

PS: Well, I am somewhat surprised by the severity of the lockdown restrictions in many countries—even in Australia, where we’ve had relatively few cases and very few deaths—and by the general acceptance of those restrictions. I see that in America now, there are some groups protesting but they seem to be very minor despite having some endorsement from Trump. And if you told Americans a year ago that they would be locked up in their homes basically and only allowed to go out for certain purposes and not allowed to meet in groups of more than, whatever the numbers are from place to place, I think they would have said, “That could never happen.” So what is interesting is the extent to which people have largely accepted that.

MJ: I’ve seen some opinions—or perhaps wishful thinking—that this serves as an example of our society being capable of making dramatic behavioral changes if faced with a large crisis. Do you think there is any reason to be hopeful by what we’re seeing about the response?

PS: So I think that what you said just then is clearly true. When faced with this significant emergency, including a significant risk of people dying—and the deaths not being previously identifiable [as being] only people of a certain group, though I suppose it’s largely people of a certain age group—then I think we can get it, we can respond in these ways. And I suppose that’s a good thing. But a lot of people that I’m reading are saying, “Well, this shows we can’t go back to where we were before this happened. This is an occasion to transform society. We’re all going to work together a lot more.” I think that is wishful thinking.

It seems to me that once this is over, the forces that have led us as societies to be as unequal as they are, as noncooperative, and not responding to the other—and ultimately perhaps even greater threats like climate change—those forces will just reassert themselves. And I don’t think the fact that we’ve been through this gives us much chance of really fundamentally changing it.

MJ: Since this translates into an economic crisis at the same time, if we’ve learned something from the previous economic crises, it seems to be that the better off seem to suffer less. And that seems to be the case here as well.

PS: Yeah. That’s true.

MJ: It’s been fascinating to see how even questioning the cost or the logic of the lockdowns and restrictions seems to invite a whole barrage of condemnation, almost a knee-jerk reaction like, “How can we even attempt to put a dollar value on human life?” Or, in this case, “avoiding a human death by a known cause.” Is this a particular challenge to utilitarian ethics or does that otherwise expose something about our deeply held values?

PS: Let’s take first the utilitarian ethics that you mentioned. I think what we were just talking about before, the fact that society has been prepared to accept these [restrictions]—that some might regard as violations of constitutional rights—is a sign that when we’re pushed, we do think along utilitarian lines. People are prepared to say, “All right. I’m going to restrict my liberties for the greater good of [mitigating] the spread of this virus.” That’s very much utilitarian thinking. When people say, “We have to do whatever we can to save lives. It’s wrong to put a dollar value on human life,” that clearly is a kind of non-utilitarian thinking. But there’s nothing new about that.

I [received] exactly that criticism in the ’80s when I started talking about the cost of saving extremely premature newborn babies with massive brain hemorrhages and very poor prospects, and I remember some editorial in a newspaper saying, “You can’t put an accountant’s pencil through a human life,” or some dramatic phrase like that. People will say you can’t, but it’s rhetoric and everybody who really thinks about it knows that you can, and you do.

The U.S. Department of Transportation will spend $9.6 million on road construction that’s calculated to save a human life, but it won’t spend $50 million. So clearly, even if you’ll spend a lot of money, there is a limit to what you’re going to spend. And I think anybody who really stops to think about that can take that point. So I don’t take the rhetoric very seriously, even if people continue to say it.

MJ: That seems to be a common rhetoric with a long history. And you’ve obviously written about the values of other lives in great detail. Speaking of other lives, your book Animal Liberation is of course a key piece of work in the animal movement and in the history of animal protection. The year 2020 marks 45 years from the first publication of the book, which has been published in multiple editions since. How has animal protection changed since the first publishing of the book?

PS: It’s changed a lot. Firstly, [animal protection] is much more of a major concern that a lot of people are involved in, beyond the “cat and dog” kind of animal protection that existed in 1975. There was really very little interest in animal protection beyond a select number of species that people were sentimental about. Mostly pets, horses perhaps, some wild animals maybe: seal calves being brutally bashed to death. But there were no major organizations campaigning about pigs and chickens, layer hens—essentially, about factory farming. There was one book that had been written about it previously: Ruth Harrison’s Animal Machines, published by quite a small publisher. There was a tiny organization called Compassion In World Farming, run by Peter Roberts, which has since grown immensely, fortunately, but it was tiny at the time. And that was really about it. There were some specialist anti-vivisection societies that had been around for a long time, but they had not succeeded in making any real changes.

The larger organizations—like the RSPCA in England—didn’t want to know about animal experimentation and they didn’t want to talk about it. All of that has now changed. We’ve got a major animal movement now. Lots of big organizations, and lots of them talking about factory farming.

We have a much greater acceptance of vegetarian and vegan food—even just in the last 10 years that’s increased. I characterize the scene in London in 1975 by the fact that the best known vegetarian restaurant was called Cranks. And that was the idea: it was catering for cranks, of course, in a bit of self-parody. But that’s how everybody thought of vegetarians—they were cranks. They had nutty theories about health or something like that, or they were pacifists, or they were Hindus, or whatever. Vegetarianism was regarded as pretty weird.

All of that has changed dramatically, and for the better. People are prepared to talk about animal rights, which they wouldn’t have talked about before at all. The word “vegan” is widely understood. Nobody would have understood that word 45 years ago. So all of that has made a huge difference.

There have been some significant improvements in treatment of animals in factory farms, especially in the European Union, where there have been various reforms to prohibit the standard battery cages, to prohibit the individual crates or pens for both cows and breeding sows. And some of those changes have [influenced] some states in the United States, including California. We’ve had some effect in other countries, like in Australia, a little bit. These things are significant because they’re affecting hundreds of millions of animals. But unfortunately that has been counterbalanced by the great increase in factory farming, in Asia in particular. As Asia has become more prosperous, the demand for meat has increased.

There are far more animals in factory farms in the world now than there were in 1975. That’s obviously a huge disappointment. There’s a lot more progress to be made. Although we have been making some good progress, it’s always hard work to keep it going.

MJ: Factory farming has intensified in its efficiency, which means more heads per dollar are produced, and in total volume, the demand for meat has increased and looks to continue to increase. Meat demand seems to be income-elastic. So as middle classes in East Asia, for instance, grow, so does their demand for animal products. We are indeed battling a growing tide of animal use. Do you think anything’s changed in the general public’s acceptance of factory farming? Is anything changing with regards to people’s knowledge about or interest in animal treatment?

PS: Certainly a lot more people know of the existence of factory farming. Some time ago, people didn’t know about it at all. I didn’t know about it until I accidentally met this Canadian student who was a vegetarian and he told me about it—and I was 24, a graduate student at Oxford! I had no idea that a lot of the animals that I’d been eating had been living confined indoors. But today I think it would be difficult for somebody going through university to not know that. It would be difficult for anyone with some interest in the world around them to not be aware of factory farming.

Just the fact that you can see products labeled organic or humane-certified suggests people will think, “What about the other products? What’s the alternative like?” Here in Australia, eggs have to be labeled. They have to either be labeled free-range, barn-laid, or eggs from caged hens. So it’s impossible to buy eggs from caged hens without knowing that they’ve been caged.

The knowledge is there. I think that very few people really defend factory farming from an animal welfare point of view. Most people you ask about it say, “Yes. I know that’s pretty bad. Probably I should try and avoid those products.” But then, [they] don’t, because if [they] get in the supermarket and look at the price difference., [they] think, “Oh, well, what difference does it make?”

In a way, the propaganda battle has been won—there’s just this big gap between convincing people that this is a bad thing and persuading them to make the commitment to directly change their product-buying behavior.

I’ve just been involved in doing some research with philosophy classes: showing them a film, having some discussion about vegetarianism, and then giving them a survey, but also getting information on their food purchases. There’s a big shift in their attitudes. There’s a much smaller shift in their food purchases.

MJ: It’s great to hear that you’ve done recent research on the topic. Because, of course, your body of work has influenced animal advocacy significantly. I just have to mention this little example: our logo at Sentient Media is a visual metaphor for “The Expanding Circle.”

PS: Oh, well, that’s nice.

MJ: Yes, we’re happy about that little visual reference. Are you working with any projects or organizations in animal advocacy at the moment?

PS: Yes, this research project I mentioned is a current one. In fact, we wrote an article and submitted it to the journal Cognition. We got a “revise and resubmit” [request] from the referees, and we’ve just resubmitted last week, and I hope that it will be out soon.

We may do some further research, actually; the next bit of the research is about the effectiveness of the film. So, in the first one, they had a discussion in the philosophy class and they saw a film. In the further one, we divided them up so that some of them saw the film and some of them didn’t. And we’re trying to see how much of the difference in attitudes and purchases is due to the film. Preliminary results suggest quite a lot. Not all of it, but quite a lot of the change in attitudes and change in behavior is related to the film they saw. That research is still ongoing.

And, I’m planning to do a revision of Animal Liberation in the next year or two, I’ve just been too tied up with other things to really make much progress on it.

MJ: Great! Exciting to hear there’s another edition in the works.

PS: At some point, yes, I hope so.

MJ: I want to bring up another topic that’s both close to our mission and related to the changes in attitudes we’ve discussed. Sentient Media’s mission is to reframe the public discussion around animal protection—and I say animal protection to encompass both animal rights and animal welfare, especially for farmed animals. We aim to do that by increasing the visibility and accessibility of animal interest stories in mainstream media. And while we already see that we are serving a growing audience, getting the animal protection message out there is still rather difficult, whether it’s op-eds or actual articles. Animal protection issues are still mostly outside the Overton window of discourse. If you agree with that assessment, do you think there are untapped opportunities for bringing these topics inside the window of discourse? And what could those opportunities be?

PS: Yes, I think there are, but the opportunities for getting coverage in the media tend to relate to those animals that people are most attracted to and most interested in. So it’s easier to get stories in the media if they’re about dogs or cats or whales or dolphins, and much harder if they’re about cows or pigs, and harder still if they’re about chickens.

And yet, I think there’s no doubt that the animal that we inflict the most suffering on globally is the chicken. So you could say it’s almost self-defeating to just focus on getting articles in the media by doing stories about cats and dogs and whales and dolphins.

That seems to me to be the big problem. So maybe you could say, “Well, we’ll do the stories about the attractive animals that the media will pick up. And that will be like a wedge to open the door, open the crack wider, and bring in the chickens as well.” But I’m not sure that that really has worked.

You get a lot of attention for something like [the film] Blackfish, but does that have any spillover for animals people are eating? Or do they all sign their petitions to free the orcas and then go and buy something at KFC?

MJ: That is a pretty accurate description of the challenge. Though recently, mostly prompted by the pandemic, we have seen very critical coverage about factory farming even in some traditionally rather conservative media outlets like National Review in the U.S., for instance. And that’s refreshing to see, because it seems like there’s a much bigger overlap [between] liberal values and the animal protection movement. Are there causes or values that the animal protection movement could find allies in?

PS: Well, firstly, I don’t think there’s anything necessarily liberal—in the American sense—about the animal cause. I remember when I was in England in the ’80s, I was working with Richard Ryder on a campaign called Putting Animals into Politics. That had really broad support. For instance, there was a Labour peer, Lord Houghton, but there was also a conservative Member of Parliament, Sir Richard Body, who was indeed quite conservative but very strong on this issue. There’s no real reason why people who are conservative shouldn’t support reducing cruelty to animals. They may not want to do it in terms of animal rights. They may talk about compassion, or mercy. Matthew Scully, in his book Dominion, talked about—he was one of the people who wrote recently for the National Review I think—

MJ: Yes, he did.

PS: Scully talked about mercy, which is a Christian term. That might have particular appeal in conservative America. But I think it should be possible to have a politically non-partisan coalition working for animals. I can’t see why not, though it depends on what the issues are. Factory farming seems to me to be contrary to a lot of conservative values, particularly in a traditional American conservatism—the small farmer being the backbone of the country. Because there’s no doubt that the growth of corporate agribusiness has depopulated the country in a way that conservatives don’t really like. So [the question is] whether anybody’s prepared to be true to those conservative values, and go against big business, because that’s the sort of choice that’s going on there. It might be possible to appeal to something like that.

MJ: Yeah, that’s very interesting. In the case of the U.S., the two-party system might make that particularly difficult. That could be a good populist platform, perhaps.

PS: That’s the other problem, the first-past-the-post voting system which leads to more polarization. But there are a number of countries where they’ve elected representatives of a pro-animal party: Netherlands, Belgium, Australia. And that’s only possible if you don’t have first-past-the-post voting.

The Upper Houses of Victoria and New South Wales now have members of the Animal Justice Party. In New South Wales, it’s relatively easy because the whole state has a proportional representative electorate.

MJ: Good. What about in academia? Have you seen animal rights or at least animal interests given more attention?

PS: Oh, yes. There’s a lot of discussion about animals and the status of animals in academic philosophy, but also now there’s this expanding area of Animal Studies, which brings in all of the humanities, sociology, literature, cultural criticism, and more. Through that area, a lot more people are encountering issues about animals. They’re not studying philosophy, which has talked about animals basically since I published Animal Liberation, but they’re coming at [animal rights] from other directions. And psychology is paying more attention as well, like the kind of research that I mentioned earlier: research into people’s choices about what to eat, cognitive dissonance between their values and what they’re eating. There’s a reasonable number of people in psychology doing research on that now.

MJ: That’s great to hear. Let me finish by asking for some advice. Much of our readership finds us because they’re researching animal agriculture for reporting and analysis, but also for school projects and other educational uses. What would your advice be for a young person looking to make a positive difference for animals in the world?

PS: People do ask me about that. Some of them are asking with the idea of doing a Ph.D. in philosophy. I tend to discourage that, because philosophy is so competitive, so unless you’re really extraordinary, right at the top of your class in everything you’re doing. you’re probably not going to get a permanent academic job. If you do, then certainly, you can have some influence through teaching as well as through research and writing. But it’s a very long shot.

I think working for some of the animal advocacy organizations, for talented people, is probably as good a way as any. I like the kind of work that Animal Charity Evaluators is doing, for instance. For people who want to go into that area and, particularly, trying to work out what kinds of advocacy are most effective, I think that’s really useful. I’ve had one student who’s gone into working with alternatives to meat from animals, and she’s working for Impossible [Foods] at the moment. And I think that’s also valuable because in the case of, let’s say, reducing factory farming in China, it’s going to be a long time before we’re going to [have an impact] by persuasion about animal welfare. But if we can produce close analogs of meat from animals that are economically competitive, and especially if they’re good for you, I think we might have some inroads there. So that’s also a valuable thing for talented researchers to get involved in.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.