Investigation

Meat Processing Plant Complaint Highlights Supply Chain Disruptions — And How the Meat Industry Isn’t Prepared

Food•4 min read

Investigation

Inside the industry most consumers don’t realize they’re supporting.

Words by James Imam

A melt-in-your-mouth delicacy with a long history, Parma Ham, also known as prosciutto, has a global reputation for luxury. Legend has it that when the Carthaginian military general Hannibal’s forces swept into Parma in 217 BC, freeing the population from Roman rule, local revelers offered their liberator slices of the meat.

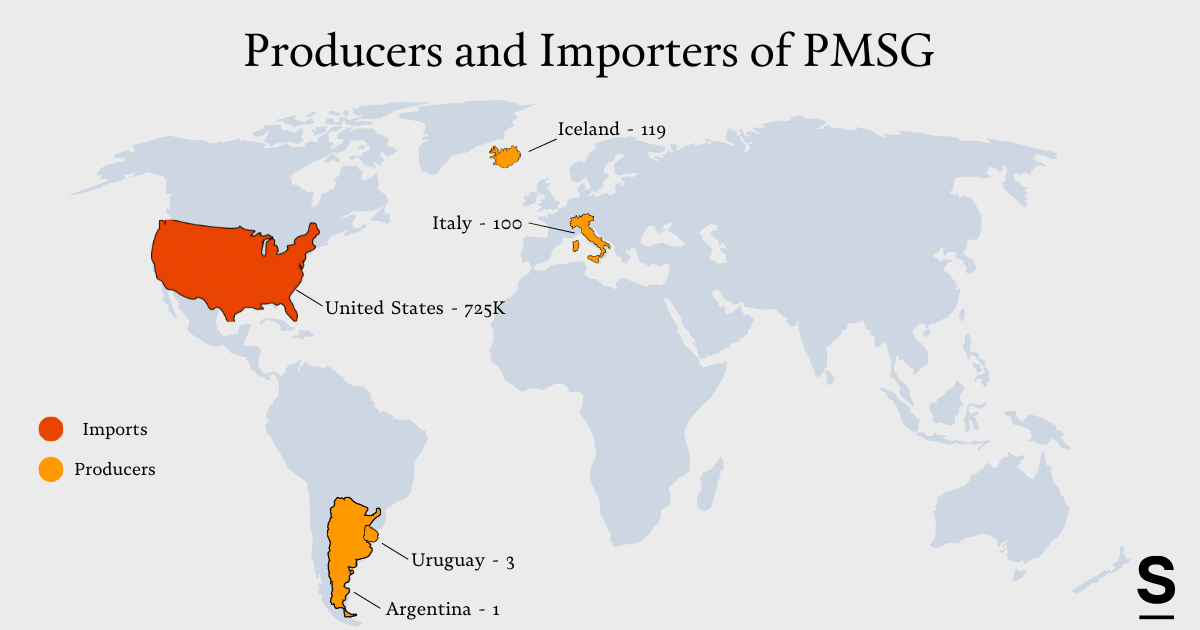

Famed for its sweet, nutty flavor, Parma Ham is still sought after around the world today, with producers near the Italian town of Parma turning out millions of legs of the ham every year. Sales are booming in the U.S. as well, now the biggest export market for Parma Ham, bringing in 725,000 whole hams in 2023.

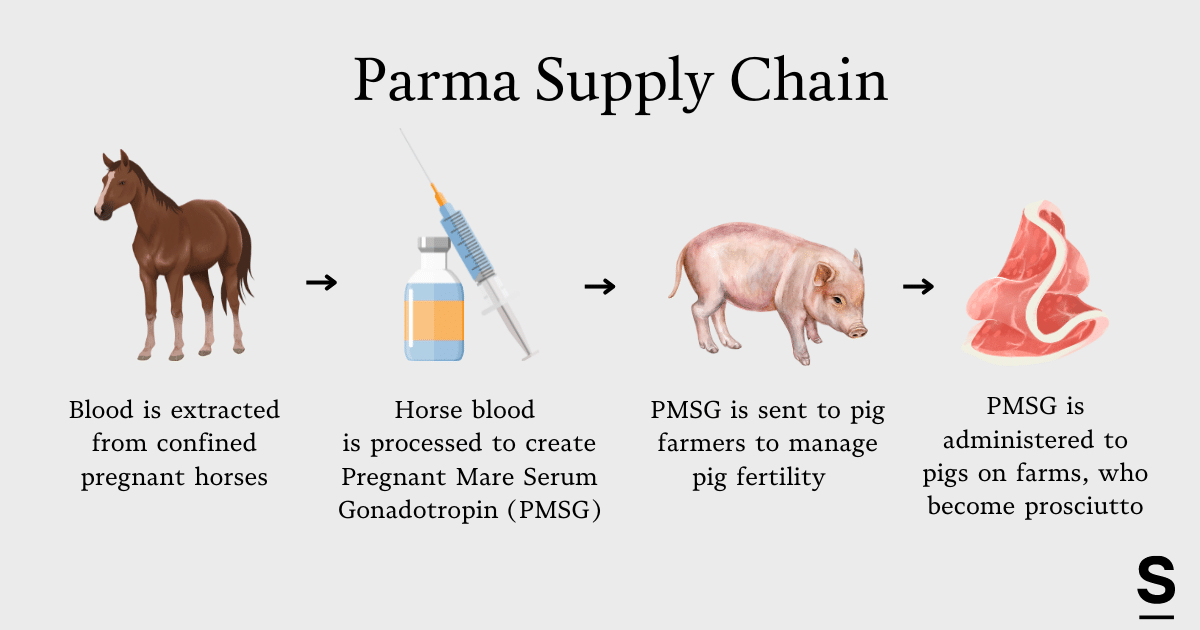

Despite the product’s global reputation for quality, however, an investigation of Parma Ham supply chains has revealed a grimmer picture. Prosciutto di Parma, as the ham is also known, is part of a global industry driving the slaughter of 1.5 billion pigs per year, as well as the extraction of a secret ingredient: the blood of thousands of horses 2,000 miles North in Iceland, on what are called “blood farms”.

The more than 100 producers of Parma Ham are all based in a hilly area of Northern Italy, stretching about three miles south of the town of Parma, in the region of Emilia-Romagna. These famed makers source from pigs that are bred and fattened on thousands of farms across Northern and Central Italy.

On its website, the Parma Ham Consortium, which represents all producers, explains that the delicacy is obtained through an age-old process that involves rubbing pure sea salt into the hind legs of slaughtered pigs, softening them with lard and placing them on racks in a dark cellar to mature. The organization portrays itself as a defender of animal welfare, announcing in March that it had circulated a new “voluntary” protocol helping all parts of the supply chain — including rearers — maintain “higher animal welfare standards” and use antibiotics “responsibly.”

Yet the marketing leaves out a few details about how the pigs themselves are raised.

In a bid to drive up profits, farmers routinely treat sows on industrial-scale farms with a hormone called PMSG, which stands for Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin. When administered to pigs, this pharmaceutical helps pork producers ensure that pigs reach puberty earlier, go into heat at the same time and give birth to unnaturally large litters.

The impact to the pigs themselves can be devastating. “The breaks between birth cycles are reduced and the number of piglets driven up, resulting in some piglets being born weak and dying shortly afterwards, and others starving to death because there are too many to feed,” Sonny Richichi, president of the Italian Horses Protection Onlus, a charity that works to protect horses and other equids, tells Sentient.

PMSG, also known as equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG), is obtained from more than one-hundred “blood farms” scattered across Iceland. Typically, handlers extract up to five liters of blood — more than four times over the amount recommended by international guidelines — from individual pregnant mares, every week, for a period of 12 weeks during the summer months.

Footage has shown horses being beaten by farmhands, collapsing from exhaustion and struggling in restraint boxes while a cannula is inserted into their jugular veins. Foals, an unwanted byproduct of the blood farms, are systematically aborted. Injured or malnourished mares are often left to die.

The PMSG industry is responsible for a “double exploitation,” says Richichi, of pigs and horses.

Amid growing outcry from animal rights groups, the European Parliament called for a ban on the importation of the hormone into the EU in 2021. Yet three years later, the ban has not moved forward, as lawmakers are still awaiting a response from the European Commission. Last September, the Icelandic government admitted that the practice of collecting mares’ blood breached EU legislation and, in November, removed a national regulation deemed to have provided blood farmers with a legal loophole. It has until 2025 to decide whether or not to authorize the collection of PMSG.

For this story, Sentient independently verified which PMSG products were available in Italy, and determined which were being used on Italian pig farms supplying Parma Ham producers. The delicacy provides just one example of how supposedly premium food products that have flooded international markets are wired into Iceland’s murky blood farms industry, rendering U.S. consumers often unwittingly complicit in the brutal mistreatment of horses.

The U.S. became the top importer of Parma Ham in 2021, leapfrogging the UK as exports by volume surged 32 percent that year. Almost 20 million packs of all kinds of Italian-style pre-sliced prosciutto were sold in the U.S. in the 12 months leading up to February of this year. The imported sliced ham makes up about 84 percent of all Italian packaged lunch meats sold in the country during the period, according to data provided by market research company NIQ. Popular brands in the U.S. include Citterio, which commands a fifth of the market share, and Del Duca, with a tenth of the market, according to Numerator TruView.

The Parma Ham Consortium, which represents all certified producers of the ham, has doggedly courted American consumers, forging promotional partnerships in 2022 with three national chains in the U.S. — including the Palm steakhouse restaurants and the Kimpton Hotels and Restaurants group.

Representatives from animal welfare organizations have called on U.S. supermarkets to stop sourcing from farms that rely on the hormone. “Extracting PMSG from pregnant mares to synchronize pregnancy in intensively farmed and often caged sows is a violent practice that can lead to serious injuries or even death for horses,” says Sarah Ison, Head of Research at Compassion in World Farming.

Yet when Sentient asked eight big U.S. supermarket chains that stock Prosciutto di Parma — Kroger, Trader Joe’s, Costco, Whole Foods, Albertsons, Shaw’s and Star Market, Safeway — whether it was right for them to stock Parma Ham, given the use of PMSG on Italian farms, none of them replied.

Other protected status dry-cured hams sold in the U.S. include Jambon de Bayonne Ham, made near the eponymous ancient port city in France, and Jamón serrano, principally made in the Spanish regions of Andalusia and Aragon.

Julia Johnson, U.S. Head of Food Business at Compassion in World Farming, says meat eaters have not been adequately informed about the pork industry’s reliance on blood farms, allowing supermarkets to sidestep the issue. “PMSG is an animal welfare issue that many consumers and companies are simply not aware of and, unfortunately, this is one of the reasons why supermarkets are not engaging on this topic,” she says. “We encourage all companies to evaluate every step of their supply chains to safeguard the welfare of animals.”

Parma Ham is just one tip of the iceberg when it comes to the enormous PMSG industry, which sources from blood farms in Venezuela and Uruguay, as well as Iceland. In 2021, Iceland had 119 blood farms and almost 5,400 mares raised for the sole purpose of giving blood.

In Iceland, the blood is collected and transformed into the powdered hormone by the company Isteka, which also runs its own farms, before being shipped to EU countries. It is possible that small quantities of the hormone are also produced within the EU. In a letter addressed to a parliamentarian in 2021,Poland’s health ministry indicated that the country sourced PMSG from other countries, including the Netherlands and the Czech Republic.

PMSG products are authorized in Germany, Spain and France — the EU’s biggest pork producers — according to the EU’s official database for veterinary medicines. Sabrina Gurtner, a project manager for AWB / TSB, wrote in an exchange of messages that the products were routinely used in Spain and Germany. Around 6.4 million doses were administered in Germany between 2016 and 2019, in a country which had an average of 1.8 million breeding sows during the period, according to figures published by the Bundestag. PMSG is also routinely used on North American pig farms, according to industry publications.

The PMSG industry is believed to generate huge profits. While none of the major EU-based pharmaceutical companies replied to requests for sales figures, a sales report for Isteka shows that the company made product sales of $1.7 billion ISK in 2022, equivalent to $12.3 million USD at the time. One-hundred grams of the hormone sells for around $1 million in its concentrated form, compared with around $6,500 for a bar of gold of the same weight, making it one of the most expensive powders on earth.

PMSG can be bought only with a prescription from a vet. In Italy, a representative of one veterinary association, who spoke on condition of anonymity, says that the hormone was used on “essentially all” intensive pig farms — a claim that was corroborated by two other Italian vets contacted by Sentient. Italy had about 16,000 intensive breeding farms and 584,000 sows in 2023, according to health ministry data.

Sentient asked Italy’s health ministry to provide an updated list of pharmaceuticals containing PMSG that are authorized for use in Italy, filing a Freedom of Information Act request, which, in Italy, requires public authorities to provide recorded information within 30 days. The ministry did not respond to the request.

However, online veterinary manuals showed that six pharmaceuticals containing PMSG as an active ingredient were listed for sale. All of the drugs that appeared in the manuals had been authorized for use in Italy, but four of them were unavailable at the time (Fixplan, Gestavet, Oviser and Fertipig, which are produced by a range of companies headquartered in South America and Europe), suggesting that distribution had been discontinued in Italy. Two of the listed drugs — PG600 and Folligon, which are produced by pharmaceutical multinational MSD in Germany — remained available for purchase.

Sentient obtained a complete list of more than 4,000 pig farmers that supply Parma ham producers. Of those willing to provide information, all said they had used PG600, with the majority saying they did so regularly. One breeder, in Emilia Romagna, said he had used numerous products on the list. Just one breeder said he had not used PMSG products for 10 years, claiming he preferred sows to go into heat naturally.

A spokesperson for the Parma Ham Consortium declined to comment on the use of PMSG on pig farms, claiming: “The Consortium does not represent and does not include, among its members, any farms.” He added: “The Parma Ham Consortium brings together and represents only Parma ham producers, i.e. 133 companies, all located in the territory of the Province of Parma, that purchase the raw material [the fresh ham] for the purpose of processing it.”

Animal rights campaigners, who have emphasized that there are 36 synthetic alternatives to PMSG on the market in Germany, have made gains in some countries. Austria and Denmark have expressed support for the European Parliament’s call for an EU-wide import and production ban on the hormone.The Netherlands adopted a motion in 2022 calling for a ban “as soon as possible.” Swiss supermarkets prohibited the use of PMSG for their label meat production in 2015, but claimed they could not prohibit it for conventional meat. However, two years ago, the Swiss pig breeders’ association banned the use of PMSG.

There are no such efforts to ban PMSG in the U.S. While sales figures for the drugs are generally not available, meaning it is impossible to pinpoint the scale of their use, they are routinely used across North America. However, rather than embrace animal welfare improvements, much of the country’s $23 billion pork industry is working to overturn the measures foreseen by Proposition 12, a 2018 law that rejects the use of narrow gestation crates and increases the minimum space requirements for pregnant pigs, claiming it will lead to “apocalyptic” losses for farmers.

In Italy, one reason for widespread PMSG use appears to be a lack of information among vets about what happens on blood farms. In a 2022 letter, which has been seen by Sentient, the National Federation of Italian Veterinary Orders wrote that the organization would “urge the veterinary medical profession to reflect on the bioethical issues related to PMSG,” but did not respond to Sentient’s request for an update.

Lawmakers should require supermarkets to make the links between meat products and blood farms clear to the public, argues Compassion in World Farming’s Ison, calling it the “responsibility of the regulators and suppliers [to] do the right thing.” In order to inform the wider public about the role of blood farms in their prosciutto, Ison says, “you need to provide clear signals.”

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.