Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Feature

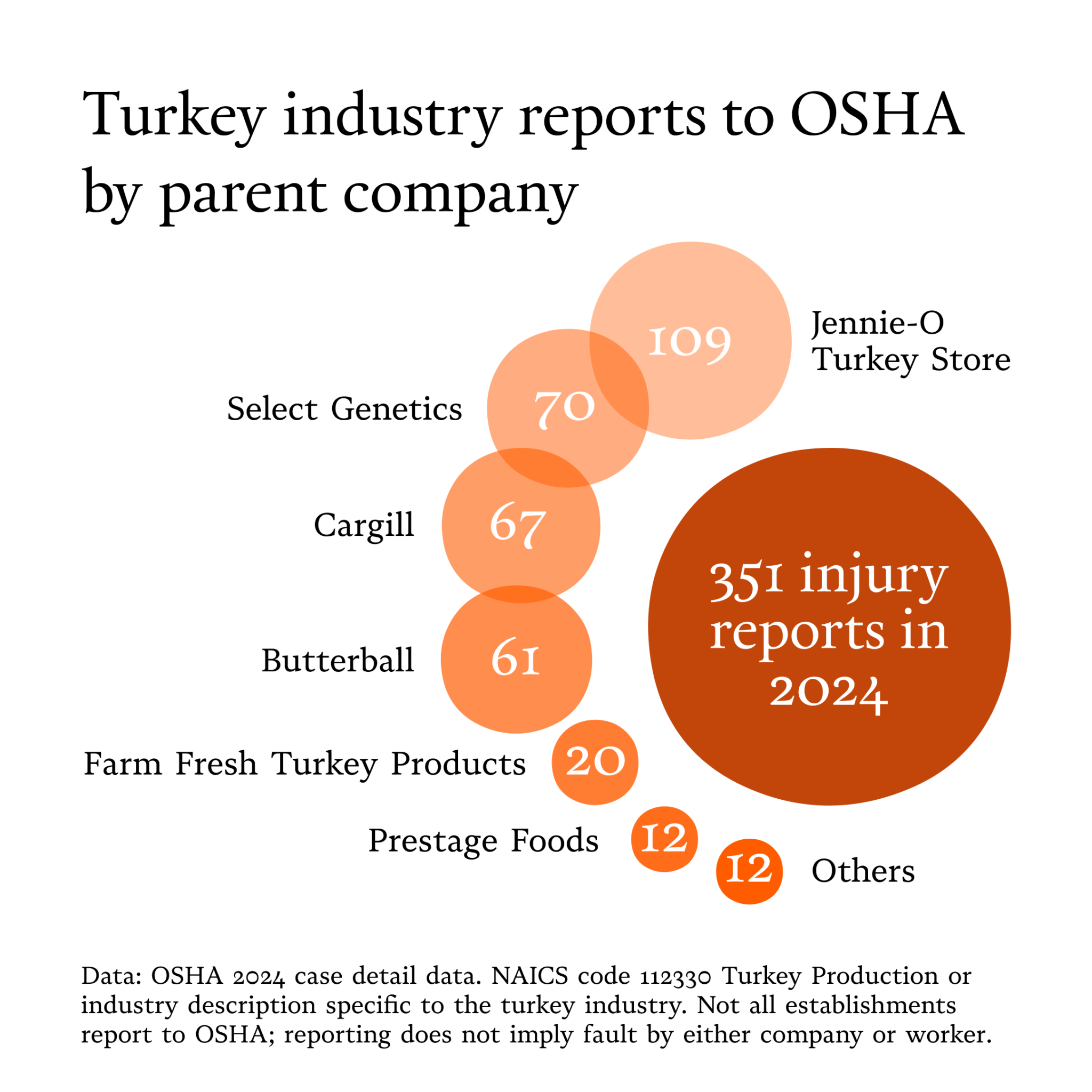

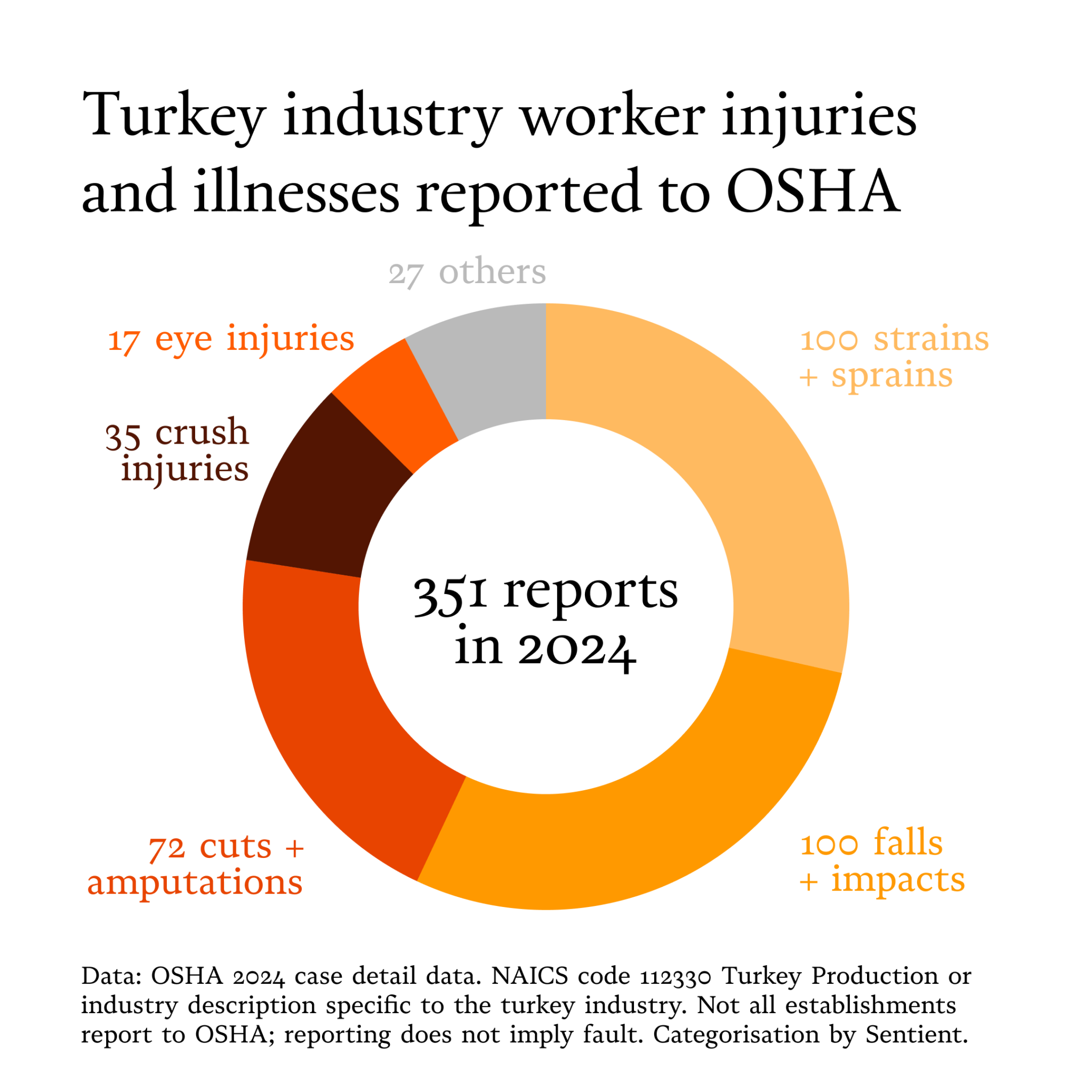

Three charts reveal details of the 351 workplace injuries experienced by turkey industry workers in 2024, which include severed fingers, injured corneas and musculoskeletal disorders.

You likely haven’t heard of the worker at a Prestage Foods plant in South Carolina who suffered a head injury after a pile of dead turkeys fell on him. Or the Butterball plant worker in Arkansas whose index finger was crushed while cleaning the gizzard peeler, a machine that separates a turkey’s gizzard from the rest of its body. Then there’s the farmworker who injured the cornea of his eye, while wrangling turkeys at a farm owned by Select Genetics in Missouri — just a few of the 351 injuries experienced by workers in the turkey production industry, as reported to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 2024.

In a review of 2024 OSHA injury and illness data, Sentient identified 100 injuries that resulted from falls, 100 sprains and strains, 72 injuries involving cuts and lacerations, including amputated fingers and hands, 17 eye injuries, 35 crush injuries and 27 other injuries and illnesses suffered by workers across every stage of turkey production, from the farmworkers collecting turkey eggs at hatcheries to the line workers processing turkeys along a fast-paced conveyer belt.

For a detailed explanation of how we analyzed OSHA’s injury and illness data, please see our methodology guide.

This data offers far from a complete tally of turkey industry workplace injuries, given that not every injury is reported to OSHA, yet it does offer a glimpse into the human cost of turkey production.

For a pay of around $18 per hour, turkey industry workers in meatpacking plants, slaughterhouses and hatcheries risk a minefield of potential injuries that can be debilitating and even fatal. In March, the Trump Administration moved to increase the line speeds in processing plants, making it harder for workers to keep up as turkey, in various stages, whizzes along the assembly line — a decision that is expected to lead to an uptick in injuries in an already dangerous industry.

“There’s a direct correlation with repetitive trauma injuries and the speed of the line,” says Jose Rivero, a workers’ compensation attorney who represents immigrant workers in Illinois, including those employed at poultry plants. “That’s been my experience.”

These injuries were spread across 50 different establishments, owned by just nine companies that produce turkey: Aviagen, Buckhead Meats, Butterball, Cargill, Farm Fresh Turkey Products (the owner of Plainville Farms), Jennie-O Turkey Store, Prestage Foods of SC, Select Genetics and West Central Turkeys.

These companies produce the vast majority of turkey sold in the U.S., including the 46 million turkeys that are eaten on Thanksgiving day every year.

Along with injuries, this data encompasses illnesses likely contracted on the job. This includes an instance of avian influenza spreading to a farmworker who was tasked with killing a flock of turkeys exposed to the virus, a process known as “depopulation,” on a farm owned by Jennie-O-Turkey Store, one of the largest turkey producers in the world.

Many of the reported injuries involved the hands, especially among workers using tools and machines in turkey processing plants.

“You see a lot of hand injuries because they’re dealing with sharp edge tools. There’s a lot of cuts. There’s a lot of amputations. There’s a lot of injuries to the hands that can turn out to be very serious,” says Rivero.

The cold temperatures in meat processing plants can also lead to numbness in the hands, adds Rivero, contributing to the high number of hand injuries. Some workers also experience the other end of temperature extremes: there were three reported incidents of heat exhaustion. One such incident involved a worker at a Butterball plant in the “blood room,” where slaughtered turkeys hang upside down by their necks, letting the blood drain.

In Rivero’s practice, the most common injuries among poultry workers arise from repetitive motions that can become debilitating over time. This was reflected in OSHA’s data to a degree: there were a total of 30 injuries attributed to repetitive movements, including four instances of carpal tunnel syndrome. However, Rivero suspects that many of these repetitive injuries go unreported, given that “it’s not a single incident that is reportable to OSHA. Repetitive trauma just kind of develops over time so it’s not as clear-cut as perhaps a single trauma.”

In one incident, at a poultry plant in Virginia owned by Cargill, a worker is reported to have developed De Quervain’s tenosynovitis, a painful swelling of the tendons on the wrist from repetitive motions. In another, a worker at a Butterball processing plant in Arkansas developed carpal tunnel syndrome that progressed into a musculoskeletal disorder, according to the OSHA report — an indicator that the injury may have been left untreated, says Rivero.

Repetitive motion injuries are often “severe enough that that tension has to be relieved with either surgical repair, injections or physical therapy,” says Rivero. “But if left untreated, you could develop a disability. You could develop contractures where your hands just freeze up, and that’s it. You’re no longer able to use your hands.”

These types of repetitive injuries, likely to worsen with the increase in line speeds, can be prevented through “10 minute, five minute breaks, just to give their extremities a rest,” he says.

The high number of injuries from falls didn’t come as a surprise to Rivero, reflecting what he also sees in his own practice. “That’s very common in the meat processing or poultry industries because the ground is covered with debris, right? So even just traversing to the bathroom, you’re at risk of slipping and falling,” he says.

Likewise, the 17 reported eye injuries didn’t strike him as abnormal, especially given that at many meatpacking plants, the policy is “you need eye protection, but that’s up to you, right? We don’t have company-issued eye protection,” says Rivero. In one incident, an employee at a Butterball processing plant developed conjunctivitis after dirty water splashed onto the worker’s eye.

There were also 12 injuries among the workers classified by OSHA as “catchers,” responsible for capturing live turkeys and loading them onto a truck to be slaughtered. In the process of trying to catch the often 30-pound birds, the catchers suffered a range of injuries, including to the eyes, elbows and shoulders. After catching the birds, they hung them upside down by the feet bound by shackles, while still conscious, known as “live hanging.”

“I’ve heard about a lot of people getting hurt during the live hanging,” says Richard Russell, who previously worked as a sanitation worker at a turkey plant in California’s Central Valley. “They’re responsible for taking them out of the cages and putting them on the hook, so you can go through the whole cleaning process.”

Russell says that his job was “physically taxing,” especially the cleaning of the scalders — massive steel tanks of hot water that loosen the feathers from the turkey carcass.

“I had to physically jump inside the scalders,” he says. “I’d basically go through and I’d spray it down. We have pressure-washing hoses that spray a little bit of bleach as well.” He’d also use a scrubber to remove the rest of the carcass residues. “After that, I would jump inside and I’d physically scrub whatever is still on the wall.”

These reported injuries represent only a segment of the total injuries endured by workers across the turkey production chain. The data is incomplete for several key reasons. For one, only turkey operations with a minimum of 100 employees are reflected in the data, excluding small turkey farms and processors. As more farms mechanize, relying on fewer employees, even large CAFOs have been deemed exempt from most injury reporting.

The data also only reflects on-site injuries and injuries that required more treatment beyond first aid — requirements that lawyers and advocates argue are vulnerable to abuse and under-reporting. For instance, meatpacking plants hire in-house nurses who allegedly limit the treatment of more severe injuries to first aid.

“We’ve heard dozens of reports from meatpacking workers and their advocates that serious injuries like musculoskeletal disorders, first degree burns and severe lacerations are treated by in-house nurses who simply provide ibuprofen and direct workers to get back on the line,” writes Amal Bouhabib, a senior staff attorney at FarmSTAND, in an email to Sentient. “Not only are those injuries not getting reported to OSHA, they are not being characterized as work-site injuries for purposes of worker’s compensation.”

When denied workers compensation, “workers are also bearing the significant costs of any later necessary treatment, including hospital and ambulance fees,” adds Bouhabib.

There is a longstanding issue of undocumented and otherwise vulnerable workers being fearful about speaking out about injuries, but the Trump Administration’s mass deportation agenda has placed an additional pressure on immigrant workers to remain silent — to a point where some employers are weaponizing workers’ immigration status against them.

“Employers are reminding them that they could have immigration problems if they pursue their [worker’s compensation] case,” says Rivero. “They’re mentioning, ‘Hey, you don’t want any problems with ICE,” to deter workers from asserting their rights. Unsurprisingly, he’s seen more immigrant workers keeping their heads down, hesitant to file worker’s compensation claims when injured. “They’re afraid of doing anything at this point,” he says.

Some of Rivero’s clients are even afraid of going to the doctor, concerned that ICE might learn the location of the medical office through their insurance. “I don’t want to say it’s an irrational fear because at this point, I don’t know what’s irrational because, you know…they’re taking people from daycare centers,” he says. He still encourages them to seek medical treatment, worried that the injury will worsen into a disability while left untreated.

Lately, he’s found himself pleading with his clients: “Hey, I get that’s a real fear, but you nonetheless have this injury, and you have to do something about it. You’ve got to see a doctor, because that’s your body. You’re not going to get another one.”