News

Republicans’ New Farm Bill Takes Aim at Animal Welfare and Pesticide Regulations

Policy•8 min read

Investigation

The U.S. has failed to contain bird flu. The $1.46 billion industry bailout is one reason why.

Words by Grey Moran

As avian flu rapidly circulates in the U.S., Cal-Maine Foods, the nation’s largest egg producer, appears to be having a bumper year, bolstered in part by taxpayer bailouts in the multi-millions.

The company’s stocks recently soared to a record high, as its net sales rose by a staggering 82 percent last quarter. Cal-Maine Foods expanded its operations last spring, paying around $110 million in cash to acquire the assets and facilities of another egg producer, ISE America. Despite culling at least 1.6 million hens on infected farms last year, the poultry corporation is getting richer and bigger.

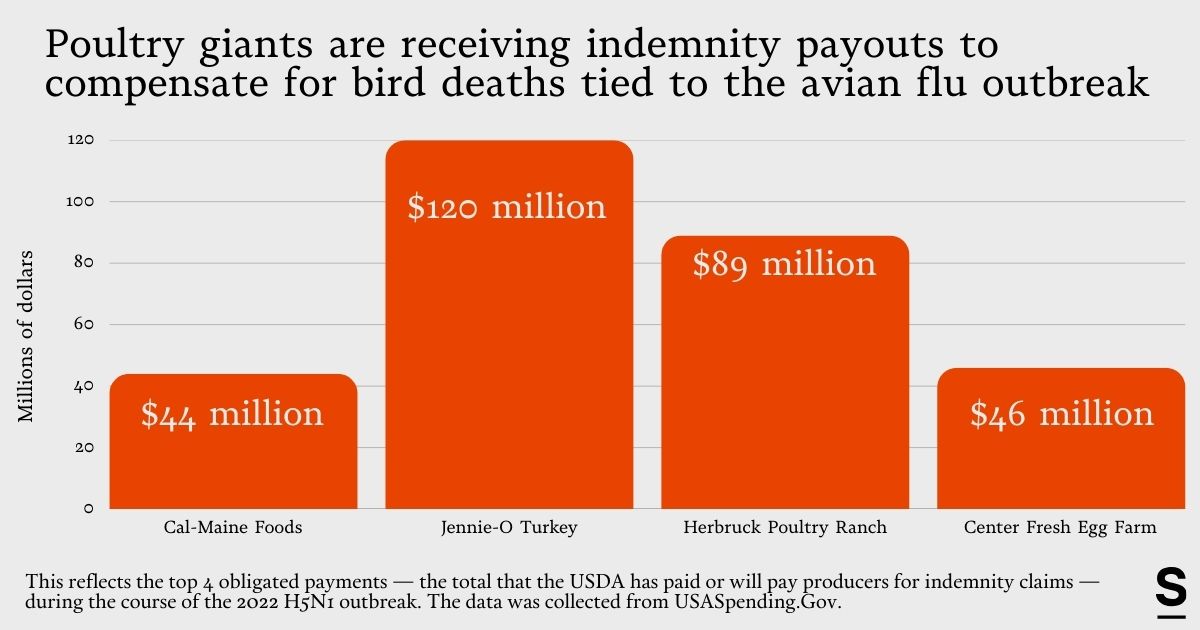

U.S. taxpayers have given the poultry giant a lift. The company has received $44 million in indemnity payouts to compensate for bird deaths tied to the avian flu outbreak. Despite the company’s growth, Cal-Maine Foods is the fourth largest recipient of indemnity payments for the ongoing outbreak from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)’s indemnity program.

The compensation system, distinct from the agency’s program for livestock, pays poultry farmers and producers for the market value of the birds and eggs. It does not pay for birds that directly die from avian flu. It only pays for “infected or exposed poultry and/or eggs that are destroyed to control the disease,” — i.e. deliberately killed to prevent the spread of the virus. The agency also provides compensation for other virus control activities, such as destroying contaminated supplies and disinfecting a barn after an outbreak.

Nearly three years since the first H5N1 outbreak in U.S. poultry, the USDA has concluded that the agency’s compensation system has not worked as it intended. By bailing out poultry producers with few stipulations, the system has, inadvertently, lowered the economic risk of biosecurity lapses on farms, encouraging the virus’s spread. In other words, farmers have not been effectively incentivized to make changes to protect their flocks.

As the outbreak has continued to spread, the government bailout of the poultry industry has ballooned too. As of January 22nd, 2025, APHIS has doled out $1.46 billion in indemnity payments and additional compensation over the outbreak’s course, according to a figure provided to Sentient by a USDA spokesperson. This includes $1.138 billion for the loss of culled eggs and birds and $326 million for measures to prevent the virus’s spread.

A significant share — $301 million — of the indemnity payments have gone to just the top four producers, according to government spending data.

Jennie-O Turkey Store, based in Minnesota, tops the list for indemnity payouts: the popular turkey brand has received $120 million since the beginning of the H5N1 outbreak in 2022, according to government spending data. Herbruck’s Poultry Ranch, which supplies McDonald’s cage-free eggs, has received the second largest bailout at $89 million. Center Fresh Egg Farm, part of a group of farms owned by Versova, one of the largest U.S. egg producers, has received $46 million. (This data reflects the legally obligated amount of indemnity owed to each company, which means that the USDA may not have dispensed these payments in full yet.)

By comparison, when the first outbreak of avian flu swept the U.S. between 2014 and 2015, farmers and producers received just over $200 million in indemnity payments.

“The current regulations do not provide a sufficient incentive for producers in control areas or buffer zones to maintain biosecurity throughout an outbreak,” APHIS stated in December, which introduced new emergency guidelines in an attempt to remedy this incentive problem.

One of the preferred methods farms use to cull birds is by sealing off the air flow to the barn and then pumping in heat or carbon dioxide. Known as Ventilation Shutdown Plus (VSD+), this is a cheap way to kill an entire flock by heat stroke or suffocation, and is approved by the USDA for indemnity payments only under “constrained circumstances.” The top 10 recipients of indemnity payments all used VSD+ to often exterminate millions of birds at once, according to APHIS records obtained by Crystal Heath, a veterinarian and the executive director of Our Honor, through a FOIA request.

By compensating farmers for VSD+, this system has helped make what many animal welfare advocates consider an unnecessarily cruel death part of the industry standard.

The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) recently released a draft of new guidelines for depopulation, which notes when the heat fails, VSD+ can result in an “unacceptable numbers of survivors” — birds that are severely injured, but not yet dead, and then need to be killed by another means. Yet the AVMA’s draft guidelines, closely relied upon by the USDA, still include this method as an option.

Some animal protection advocates contend that poultry companies should not receive indemnity payments at all, regardless of biosecurity, arguing that the industry should be responsible for its own losses.

“Why should this high-risk business be bailed out?” Heath, a longtime critic of AVMA’s guidelines, tells Sentient. As an animal protection advocate, Heath has also been closely tracking indemnity payments throughout this outbreak. “What we’re seeing is the largest corporations are receiving the most in indemnity payments, and they’re using the most brutal methods of depopulation,” referring to the culling methods.

The bailout is set to only expand as H5N1 spreads, prompting the mass culling of more domestic flocks, in what has become the largest foreign animal disease outbreak in U.S. history. The egg industry continues to be roiled: over 20 million egg–laying chickens died from either culling or the virus in the final quarter of last year.

More recently, on January 17, 2025, HPAI was detected for the first time in a commercial poultry flock in Georgia, the top producer of poultry in the U.S., deepening concerns about the struggle to contain the prolonged outbreak.

The indemnity system was designed to incentivize producers to adopt practices that help curb the spread of the virus. As APHIS states, the payments are intended to “encourage prompt reporting of certain high consequence livestock and poultry diseases and to incentivize private biosecurity investment.” Biosecurity measures include a range of practices to prevent disease outbreaks, from latching dumpster lids and disinfecting equipment to more expensive measures, like installing netting and screens on barns to deter wild birds.

These biosecurity measures are especially critical given that H5N1 is most commonly introduced to poultry flocks through wild birds, according to a 2023 epidemiology analysis conducted by APHIS. The virus’s transmission from wild birds can happen either directly, or indirectly through contaminated feed, clothing and equipment.

By sheltering producers from risk, researchers have observed that indemnity payouts can, under some circumstances, inadvertently encourage lapses in biosecurity, enabling the spread of disease. And this can potentially create a system where farms are too indemnified to fail — the risks of operating a business highly susceptible to disease are absorbed by the government.

“What we are finding is that ‘unconditional indemnity’ disincentivizes livestock producers to adopt biosecurity because they know that if the disease strikes their system then they would be indemnified,” Asim Zia, a professor of public policy and computer science at the University of Vermont who researches livestock disease risk, tells Sentient. According to Zia, “unconditional indemnity” means indemnity payments with next-to-no requirements to qualify.

It remains to be seen whether APHIS’s new interim guidelines — which will require that some high-risk producers successfully pass a biosecurity audit prior to receiving indemnity — will be enough to remedy this issue and encourage producers to change. Unlike the previous system, the new audits will include a visual inspection of the premises, either virtually or in-person. However, the scope of the new rule is limited to large-scale commercial poultry facilities that have been previously infected with HPAI, or that are moving poultry onto a poultry farm in a “buffer zone,” a higher-risk region.

Other large-scale commercial facilities will still follow the earlier rule’s more lenient audit process. This requires an audit of a producers’ biosecurity plan on paper — not an inspection of the actual poultry farm — every two years. It has been remarkably easy for farmers to pass this audit: the failure rate of this program was zero, according to APHIS, which made it so there were effectively no strings attached to the payouts. And smaller-scale poultry operations are entirely off the hook, exempt from both rules, and even from developing a biosecurity plan.

In the past, APHIS has repeatedly bailed out many of the same poultry businesses, spending $227 million on indemnity payments to farms that have been infected with H5N1 multiple times. This has included 67 poultry businesses that have been affected at least twice, and 19 companies that have been infected at least three times, according to the agency’s own records.

APHIS has not released the names of the companies that have been repeatedly infected, though the indemnity payments provide a glimpse into this.

Take Cal-Maine Foods’ poultry farm in Farewell, Texas. On April 2, 2024, Texas’s Commissioner of Agriculture Sid Miller announced its flock tested positive for H5N1, requiring the culling of 1.6 million laying hens and 337,000 pullets. The very next day Cal-Maine Foods, headquartered in Mississippi, received an indemnity payment of $17 million for HPAI detected on the Texas operation, according to government spending data.

Last November, Cal-Maine Foods’ executives joined other business leaders across industries at an annual investment conference, ringing in the year on an optimistic note. As avian flu decimated flocks, the company’s top executives were focused on the future.

“We still think there’s going to be good opportunity to grow,” Max Bowman, Cal-Maine Foods’ vice president and CFO, told business leaders. “We got a playbook for the whole market. And so right now, things are great, but we think we can continue to build this company,” which, as it stands, controls one-fifth of the domestic egg market in the U.S.

The company is already in the process of building five new cage-free facilities, adding 1 million hens to their flock, in Florida, Georgia, Utah and Texas.

Bowman, Cal-Maine’s Vice President, did not reply to Sentient’s request for comment.

Other poultry companies are expanding too. For instance, Demler Farms in San Jacinto, California is building a triple-story egg operation right next to a dairy farm, which is also susceptible to the avian flu now that it has spread to cattle. Adding to this risk, the San Jacinto Valley is a critical habitat for migratory water birds, the primary hosts of avian flu.

Most of California’s cases of avian flu in poultry have been clustered along this water bird migratory route, known as the Pacific Flyway. Yet this appears to not be enough of a deterrent for Demler Farms’ expansion. As Heath observed, this risk is softened by the indemnity payment system, ready to bail out infected poultry farms by the millions.