Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Feature

The dairy industry in Vermont relies heavily on immigrant hires, workers who are now being detained and deported. And sometimes freed.

Words by Grey Moran

On a cool May afternoon, a group of Vermonters crowded into the cheerful, teal-painted headquarters of Migrant Justice, a human rights organization led by immigrant farmworkers. The team of over a dozen volunteers assembled quickly, in just a day’s notice, in order to show support for two young detained farmworkers: Jesus Mendez Hernandez, age 25, and Adrian Zunun-Joachin, age 22, coworkers in the dairy industry. Some lived nearby in Burlington. Others traveled for hours from more rural parts of northern Vermont, a lush, hilly region known for its dairy farms and tight-knit, trusting communities where it’s custom to not lock your doors. That same neighborly spirit is now rising in defense of farmworkers targeted by expanded immigration raids.

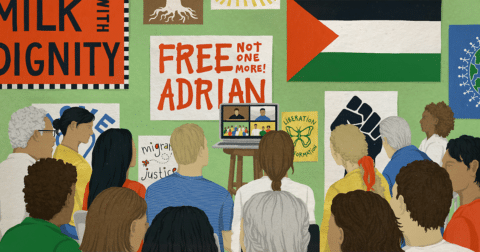

Many of the volunteers belong to Migrant Justice’s rapid response network, a list of nearly a thousand people that get text alerts when they need to quickly mobilize. Lately this network of volunteers has been called on again and again — for emergency protests, to document and observe detention incidents and to show support at hearings like these. On this particular afternoon, the organizers came together to watch the virtual bond hearing of Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin, hoping they would be freed on bond.

If that happens, the bond will be paid by the Vermont Freedom Fund, a statewide, volunteer-run bail fund that works closely with Migrant Justice to pay the bonds for detained farmworkers. “There are just so many good-hearted people in Vermont who know about us, and they send us money,” says Lisa Barrett, the only active member of the bail fund. To her surprise, two of the farmworkers, recently freed on bond, have fully reimbursed the bail fund, Barrett tells Sentient. “These guys are so community-minded,” she says. “They want to be sure that we have the money to bail out the next person.”

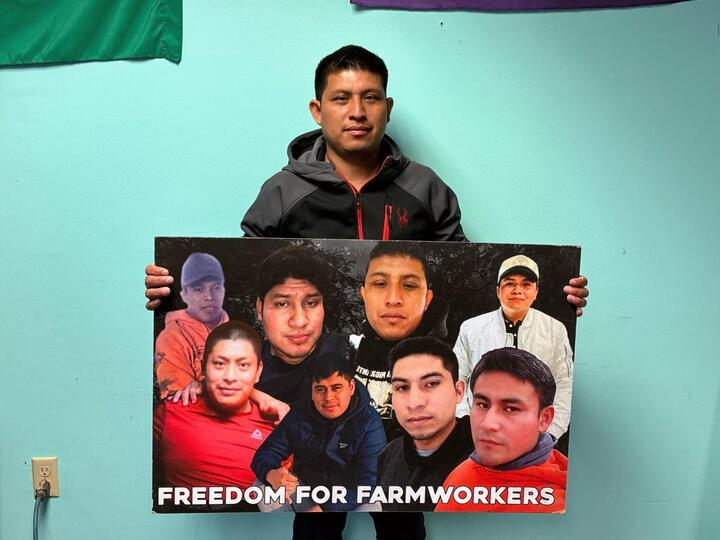

These particular dairy workers, Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin, were apprehended on April 21 at what is both their home and workplace: Pleasant Valley Farms. This farm is the largest dairy operation in Vermont, raising 3,000 cows just a few miles from the Canadian border. Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin were arrested along with six of their coworkers in what’s been described as one of the largest immigration raids in Vermont’s recent history. They were later abruptly transported — without any notice to their loved ones or lawyer — to a detention facility in Karnes County, Texas, separated from their friends and family by thousands of miles.

An estimated 1,000 undocumented migrants — primarily from Mexico and Central America — form the backbone of Vermont’s dairy industry. It’s grueling work: dairy farmworkers often endure 12 hour shifts, seven days a week. The vast majority earn less than the state’s minimum wage, according to a survey conducted by Migrant Justice. Unlike other agricultural workers, dairy workers typically are employed year-round, which means workers tend to put down roots where they work and reside, making strong connections with their fellow residents.

Those fellow residents have been showing up for farmworkers like Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin who have been threatened by deportation. “There is a community both fighting and waiting for them to return home,” Su Ughetti, one of the volunteers who lives a few towns over in Essex, tells Sentient. Ughetti, who decided to virtually attend the bond hearing in order to show Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin “that they are not alone,” has participated in other bond hearings for Vermont immigrants. Showing up in this way helps ease her own distress, she says. “It feels a lot better than not doing anything about it.”

Just before the hearing was expected to begin, Ughetti and the other supporters pushed their chairs close together, attempting to fit all of their heads within the narrow frame of the laptop camera — a similar gesture to packing a courtroom. They hoped to be visible to the farmworkers, who had been detained for about a month by that point, with little outside communication. The feelings of duress are often made worse by the fact that the farmworkers are so far from their home in Vermont.

“Being in immigration detention is so traumatic and so isolating, and there’s so much pressure on people to just give up and accept their deportation,” Will Lambek, an organizer with Migrant Justice, a group that has been on the frontlines in providing detention support, tells Sentient. ”So knowing that there’s an organized community outside the bars that are fighting for you and pulling for your release gives people the strength that they need to stay in it and fight the cases.”

The volunteers are also hoping to be visible to the immigration judge. Community support sometimes has the potential to favorably sway the determination of a bond hearing, says Lambek, to show the judge “that they have roots in Vermont, that they’re part of the community here.”

The idea is to persuade the judge that the detainee can be trusted to show up to future court hearings rather than flee, says Brett Stokes, a lawyer representing the detained farmworkers and the director of Vermont Law School’s Center for Justice Reform. “It’s pretty telling that a lot of people took the time to be there to support that person. I think that that does go a long way with the court,” Stokes tells Sentient.

When supporters show up, it also gives the judge a glimpse into the farmworkers’ lives and social networks. It can serve as a reminder to the judge of their humanity, something that is so often lost in the deportation process. “For the judge to have to look at people that support this person — it really humanizes them,” says Stokes.

Just that morning, José Edilberto Molina-Aguilar, who was swept up in the same raid on Pleasant Valley Farms, was freed on bond. And a few days prior to this hearing, Migrant Justice leaders and supporters welcomed home Diblaim Maximo Sargento-Morales, another coworker on the same dairy farm, who also goes by Max, was released at the lowest possible bond amount, or $1,500.

It was a sweet moment of victory: a welcome crew met him at the airport to drive him home, showering him in applause and cheers of “Sí se pudo!” (Yes, it was possible!). In a video, Max appears visibly dazed but is smiling from ear-to-ear.

It’s a success that Migrant Justice has replicated with three recent detention cases so far, calling upon the community support they’ve forged through years of organizing in Vermont. These cases have also received a rare outpouring of support from local politicians, including nearly a hundred state elected officials who signed onto a letter asking the Department of Justice to free the detained farmworkers.

“The speed and efficacy of the response is due to the groundwork that we’ve been laying now for over a decade,” says Rachel Elliott, an organizer with Migrant Justice. Some of the detained farmworkers were involved in “public outreach, community building and trust building,” she says, which has helped them cultivate a wide network of support. The political climate has also motivated the volunteers. “People are especially energetic right now because of the current political situation and are even more willing than usual to step up and stand in solidarity,” she says.

“People are continuing to be persecuted and criminalized and detained in Vermont and around the country,” says Lambek, addressing the volunteers who had gathered for the bond hearing. “With some of these cases, we’ve shown that it is possible to interrupt that process through community organizing and support.”

But this particular bond hearing didn’t go as planned, Lambek acknowledges. The support team had waited for several hours as the hearing was significantly delayed, but they eventually received the news that the judge presiding over this case had decided to not let them in the room.

Stokes, who was the lawyer on this case, urged the judge to let them in, explaining that it’s a room full of people demonstrating support, but the request was denied. “I have literally never been in a situation like that,” he says.

In the end, the judge decided that both Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin posed a “flight risk,” and denied them bond entirely. The bar was unusually high, according to Stokes. The judge reasoned that since the two dairy workers would likely not be eligible for forms of relief from deportation like asylum, they therefore would not show up to court — despite the fact that they have a legal and advocacy team to support this process.

This was an especially challenging outcome for Zunun-Joachin. The dairy worker’s health has deteriorated so quickly and significantly in detention that he had to attend his bond hearing from the hospital while bed-ridden.

In May, Stokes petitioned the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials on Zunun-Joachin’s behalf to receive humanitarian parole, which would have released him from custody to receive urgent medical care. After a month of waiting, the petition was denied in late June, without any explanation, beyond that it was “deemed not appropriate.”

It’s hard to predict what will lead to a successful outcome in deportation cases. The system itself is unpredictable. This affords both immigration judges and ICE a lot of discretion, even when they are following the law.

On top of this, according to Stokes, it is not uncommon for immigration enforcement officials to overstep the bounds of the law entirely.

Four Vermont farmworkers have been deported under a process known as expedited removal, without ever seeing a judge. They have been denied due process, alleges Stokes — specifally, each was denied a fear screening to determine whether it was safe for them to return to their countries of origin, which is required in expedited removal cases where there is a credible fear of persecution or torture. “I know from speaking to each four of those individuals that they did express a fear of return and had no access to these credible fear screens,” he says. DHS is supposed to offer these screenings but they did not in these cases, Stokes says.

Even after a judge grants release, there can be more delays. On the day of the hearing, Migrant Justice was awaiting the return of Arbey Lopez-Lopez, another community member whose bond was fully paid thanks to the Vermont Freedom Fund. Yet he remained stuck at the New Hampshire federal prison FCI Berlin.

Lambek gave the crowd of supporters gathered for the bond hearing an update. “ICE has just for a couple of days now refused to let him out of jail,” says Lambek. “It’s just another example of the capriciousness and injustice of the system.” Even after the judge grants release, Lambek says, “ICE can just drag their feet for three more days.”

Still, there was one small moment of victory for the advocates gathered that afternoon. As the crowd of Vermonters idly waited for the hearing, Migrant Justice leaders received good news from their legal team, who are in contact with the lawyers representing activists for Palestinian freedom who have been detained.

A Palestinian flag is displayed prominently on Migrant Justice’s office walls; a show of solidarity between the two groups. Those gathered learned that Mahmoud Khalil, the Palestinian student activist previously detained in Louisiana, would now be granted permission to meet his month-old son for the first time.

The room erupted in cheers. “At the end of the day, we are a human rights organization,” says Elliott. “We are deeply concerned with collective liberation and see the struggle for the liberation of Palestine and the end of the genocide as inextricably tied with the liberation of our community members here at home.” For Vermont’s Migrant Justice, even though Hernandez and Zunun-Joachin were denied bond, there was still a small victory that day, for collective human rights.