Investigation

Meat Processing Plant Complaint Highlights Supply Chain Disruptions — And How the Meat Industry Isn’t Prepared

Food•4 min read

Reported

Open farm days are curated to show the public only what the meat industry wants you to see.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

As I made my way through the barns of the discovery center, the smell of farmed animals wafted in the air along with the odor of sizzling meat. Kids wore paper pig ear headbands and clutched coloring books about bacon as they ran through the barns, bursting with the joy of a day at the fair. But this free day of family entertainment is part of a much bigger plan.

Called the Bruce D. Campbell Farm and Food Discovery Centre, this educational farm first opened to the public in 2011 in Manitoba. The hog farming capital of Canada boasts 540 hog farms and 3.3 million hogs in the province as of 2022, about as many pigs as in Nebraska. The center describes itself as “hands-on” and for “children of all ages,” a place “to explore the ways food is grown, raised, and made in Canada.” The public sees sanitized, miniature versions of hog, dairy and egg farms — a few dozen animals per space as opposed to a few thousand. You can also host birthday parties there.

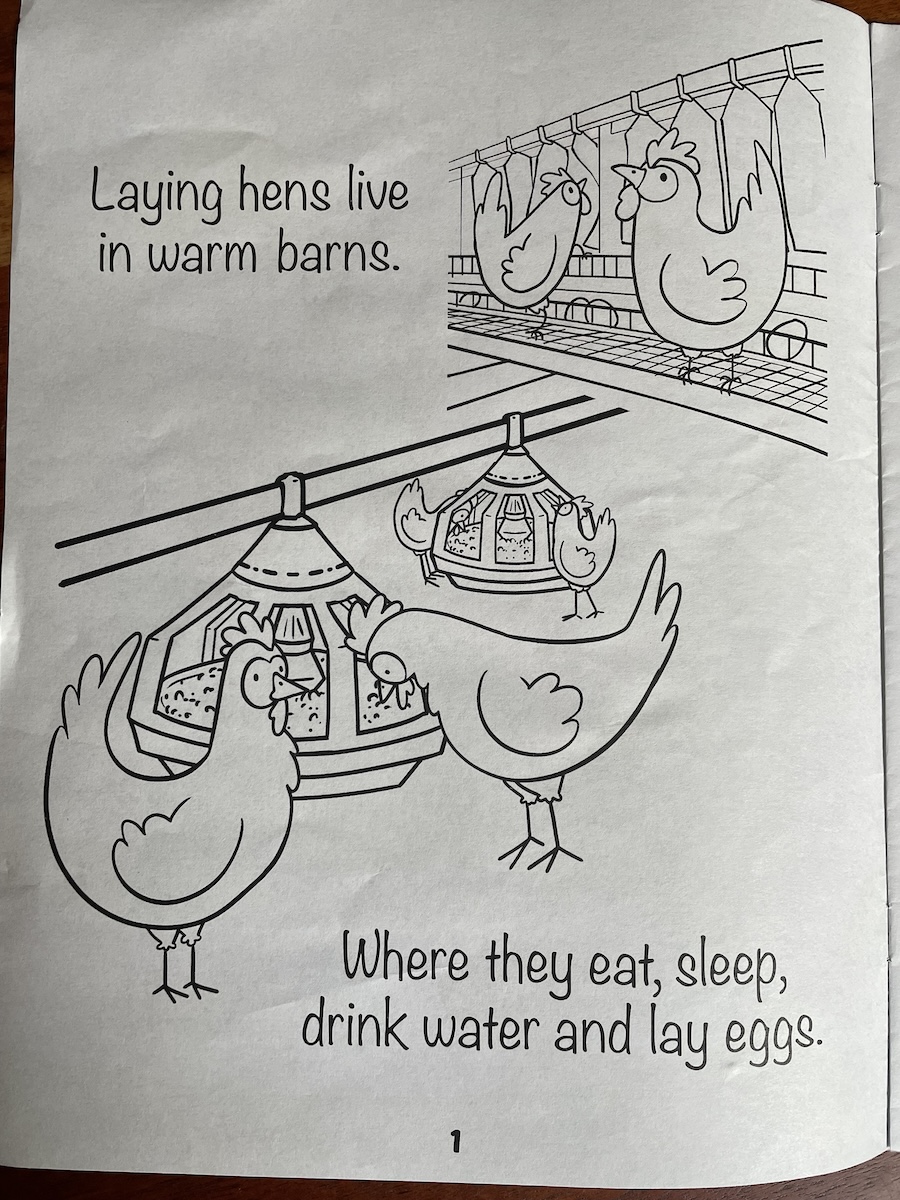

On that Sunday in September, the center hosted its second annual Discover the Farm event to “meet local farmers” and “see live animals.” My daughter and I were there with hundreds of other families, listening to industry representatives tell us about “warm barns” where hens “enjoy living shoulder to shoulder,” “farrowing pens that provide sows comfort and privacy,” and stories about “natural life cycles” that end with vagaries like “processing” and “going to market.” What we found was far from an honest farming experience, and certainly nothing like what animal advocates routinely find when documenting farming spaces. Rather, what we discovered was a propaganda carnival for kids, complete with pristine barns, happy cartoon pigs in farrowing crates and industry reps peddling marketing as education.

So-called “open farm days” are nothing new. Rooted in agricultural shows and fairs that have been held for centuries, farmers have long shared aspects of food production with the public. But over the last decade, the meat industry has taken things a step further, inviting consumers onto working farms that are dressed up — or in some cases specifically designed — for public display.

The goal: address rising consumer concerns about transparency. According to a recent survey from Merck Animal Health, two thirds of American shoppers consider transparency in the animal protein supply chain to be extremely or very important. We can trace that greater desire for transparency back to an uptick in undercover investigations of slaughterhouses and industrial animal farms.

Grace Platte, a staffer with the Animal Agriculture Alliance, told Brownfield that the industry group wants consumers to go to farms in order to see first-hand where food comes from and how farmers treat the animals. “Consumers, more than ever, are hungry to learn about where their food comes from and how our food makes it from farm to fork.”

Founded in 1987, the Animal Ag Alliance’s original purpose was to track and respond to the growing animal rights movement that, at the time, was just beginning to expose the way animals are raised and slaughtered on factory farms. Since then, the movement has, of course, grown exponentially. Added Platte, “we want to create more transparency to our consumers to show them that we as an industry care about animal welfare more than anyone could.”

The meat, dairy and egg industries have been tackling their growing public relations problem in a number of ways, including paying influencers and funding academic researchers to craft communications research. Open farm days are yet another tactic. Or as political economist and assistant professor Jan Dutkiewicz explains it in his paper on the subject, “the last decade has seen the industry turn to a new strategy: aggressive public relations outreach rooted in the paradigm of transparency.”

Open farm days are promoted as opportunities for the public to visit specific working farms on specific days, to get a peek into operations that are typically hidden from public view. But as Dutkiewicz puts it, “Generally, these are highly mediated public relations exercises.”

Advises industry news outlet The Pig Site, farmers can put their best face forward on open farm days with “meticulous planning.” Jennifer Farwell, agricultural economic development specialist at Cornell Cooperative Extension of Madison County, told The Pig Site that farmers should prepare for the types of questions visitors could ask, “particularly when it comes to practices that might seem odd to urbanites.”

For example, “If your poultry do not have access to the outdoors, be prepared to answer why,” says Farwell. Consumers are often surprised to learn that even chicken labeled and sold as “free-range” might be a myth, as one Tyson Foods representative admitted in the presence of an undercover investigator.

Farwell’s recommendations highlight that there are the parts of farming that the industry wants the public to see, and then there’s the rest. “Using signs that say ‘Authorized personnel only’ will help keep people out of specific barns or areas.” People visit open farm days not only to gain more information about farming and how animals are raised, said Farwell, but they also want “reassurance that this is done in a sustainable and safe way.”

In other words, open farm days offer reassurance by presenting snippets of the truth bathed in warm falsehoods — giving consumers just enough information to convince them they’ve done their due diligence, while keeping the tough stuff hidden. That tough stuff is what activists, undercover investigators and whistleblowers find when they enter real farming spaces on working days, and discover scenes that look very different from a typical open farm day.

The Canadian pig farm I saw on Discover the Farm day, for example, showed mother pigs roaming around in an open, brightly lit and clean “gestation barn,” while the farrowing crates conveniently sat empty. In reality, industrial pork producers keep pregnant pigs in crates — often as small as 7 feet by 2 feet — until they give birth and their piglets are weaned. Though the practice has been limited or banned in nine U.S. states, it’s still the norm for most of the pork industry around the globe.

The animals I observed appeared healthy — though perhaps bored — and relatively clean, a far cry from what has been documented by undercover investigators and activists from other pig farms in Canada.

In 2020, an undercover investigator in the neighboring province of Ontario, captured disturbing scenes from a pig farm, including animals trapped in cramped crates, artificially inseminated by staff and squealing at having their tails roughly cut off without anesthesia. Similar footage recorded by activists in 2019 from inside a pig farming operation in Quebec, shows hundreds of animals living in dark, barren barns, and unhygienic conditions. While activist footage from a British Columbia farm that same year also shows pigs trapped in crates, along with bodies of deceased pigs in varying degrees of decomposition.

The U.S. is home to a similar fairytale farm, called Fair Oaks. Dubbed “Dairy Disneyland,” and the “Disneyland of agriculture,” Fair Oaks Farms offers family-friendly, agricultural-themed attractions nestled amongst its working farm operations. It relies on “strategic revelation – including literal glass walls – ” notes Dutkiewicz, “to craft a publicly palatable narrative about factory farming and factory-farmed animals.”

A journalist for Pacific Standard magazine visited the tourist attraction in 2018, describing it as “flashy and pastoral — and aggressively cheesy (a milk-carton scene come to life).”

Glossed over on the tours, the article notes, are the less marketable aspects of everyday farming: confining pregnant sows to gestation crates, dehorning dairy cows and castrating animals without painkillers. Soon after the article was published in 2019, an animal rights group published undercover footage from the farm showing disturbing abuse of young dairy calves.

I write critically about animal agriculture; a lot. In reaction to these stories, I am often told by people in the industry that I don’t know what I am talking about, that farmers care about their animals and to ‘go visit a real farm and see for yourself.’

I am still waiting for an invitation. Because like much of the public, I cannot simply walk onto a farm and take a look around. In fact, as a result of activists doing just that, legislation has been put in place in the U.S., and now Canada, often referred to as ag-gag laws, to deter people from entering agricultural operations.

What is often found and shared from within those spaces is in stark contrast to the curated image of animal agriculture that the industry puts forth to the public. This contradiction then feeds into an already cautious consumer base that today wants more information about where their foods come from, and to feel good about what they learn.

As Dutkiewicz writes about Fair Oaks Farms: “It attempts to make the public comfortable with the factory farm, creating a new affective baseline through controlled acculturation. It is also a model farm, an ideal without the abuse, the defects, and crucially without the killing.” Crucially indeed — because there certainly is no Open Slaughterhouse Day. And I won’t hold my breath for an invite.

As families at the Discover the Farm event munched away on their free pulled-pork sandwiches while gazing at actual piglets, it struck me that the public relations tactic was working. This desensitizing endeavor was meant to sell consumers and their kids on the idea that farming and eating animals is not only ok, but fun.

No one questioned why the farrowing crates were empty or the piglets had no tails. No one questioned why the dairy cow mothers were kept separate from their small calves who bottle fed. Because no one was there to be deterred. They were there to be assured. And it worked.