News

Key Iowa Swing Districts in U.S. House Could Hinge on Water Quality and Cancer Concerns

Elections•5 min read

Feature

The H-2A visa program, which recruits farm laborers largely from Mexico, has been likened to indentured servitude. The dairy and meat industries want in.

Words by Grey Moran

As immigration raids escalate, the Trump administration has vowed to overhaul and expand the H-2A agricultural visa program. This could open the door for the dairy and meat industry to participate in the program, which recruits workers from foreign countries — the vast majority coming from Mexico — to work on U.S. farms. This would establish a workforce of virtually unlimited, low-wage workers — with very limited rights, prone to exploitation — for the meat and dairy industry to tap into whenever there is a labor shortage.

As it stands, the H-2A program is limited to seasonal agricultural workers, who work in the U.S. for up to 10 months per year. This excludes most of the year-round jobs on livestock operations, but this could change as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, lawmakers and agricultural industry groups push for the H-2A program to grant year-round visas. It’s a move that would require congressional approval, but the Trump administration has repeatedly expressed support for this change under pressure from the meat and dairy industry.

“Dairy production is a seven-day-a-week, year-round endeavor. Our cows require constant, daily care and handling. Unlike most other agricultural production, there is no ‘season’ in dairy production,” said Harold Howrigan in testimony before the Senate in February 2025, as the second Trump administration launched its first immigration raids. “Unfortunately, this nation’s single agricultural visa program, the H-2A program, focuses on a seasonal or temporary need for workers, and excludes dairy farms with year-round needs from participation.”

The meat processing industry has also been vying for H-2A farmworkers, which would require additional regulatory changes to accommodate. The program is currently only open to agricultural industries as classified by the Department of Labor, which does not include any food processing industries. Instead, some meat processing plants employ H-2B workers, a visa program for non-agricultural seasonal employees.

The H-2A program has been hailed by lawmakers and agriculture industry groups as a “legal solution” to labor shortages, which have worsened as the Trump administration carries out mass deportations. Yet the program has drawn sharp criticism from farmworker and human rights groups for creating conditions of exploitation, as evidenced by the program’s long history of wage theft, human trafficking, and other abuses.

On top of this history, 2025 saw severe cuts to H-2A workers’ wages, projected to amount to a loss of around $2 billion dollars in 2026. This could also massively depress the wages of domestic farmworkers, which are tied via policy to H-2A workers’ wages. It’s a move that United Farm Workers, the largest farmworker union in the U.S., has described as “one of the largest wealth transfers from workers to employers in U.S. agricultural history” — a wage cut that will deepen if the H-2A program is expanded into more industries and year-round jobs.

“There are too many flaws for the H-2A program to be expanded in any way,” Leticia Zavala, a former farmworker and organizer, tells Sentient. Zavala is the co-coordinator of El Futuro es Nuestro, a human rights group led by H-2A farmworkers in North Carolina. “For it to be expanded in any way, first the flaws need to be addressed and protections put in place.”

The H-2A program is the only visa program without an annual limit on the number of foreign workers recruited, one of the primary reasons why the meat industry is looking to expand into employing H-2A workers in addition to H-2B workers.

“Nobody wants to be an H-2B because there are a limited number of visas. Everybody wants to be an H-2A,” says Greg Schell, a legal aid attorney for Southern Migrant Legal Service in Florida. “We’re going to see this continued growth in H-2A. We’re going to see pressure elsewhere as the non-agricultural jobs try to get more workers in there.”

This projected expansion of the H-2A system would have major ramifications for the future of labor in the food production sector. The visa program, which more than tripled in size between 2012 and 2021, has been the subject of contentious disagreement within Congress and even immigration and farmworker groups for years — a debate often hinging on the need for accessible forms of legal immigration and the rampant labor abuses and human rights violations that have plagued the H-2A program for its entire 33-year history.

The structure of the H-2A program has been compared to indentured servitude because it grants employers a high level of control over workers: the visas are tied to a single employer, who also provides their housing, transportation and livelihood. If an H-2A worker is fired, they don’t just lose their job. They lose their right to live and work in the U.S.

The expansion of this model to a year-round workforce would effectively establish a new class of permanent, low-wage workers, with few rights and no economic mobility.

“It’s a really horrible idea and a little dystopian to bring in people on a temporary visa to make them ‘permanently temporary’,” says Daniel Costa, the director of immigration law and policy research at the Economic Policy Institute.

“The program was created to fulfill temporary shortages and seasonal jobs. If you want a program that brings in workers for permanent, year-round occupations, you need to bring them in on green cards, which are permanent immigrant visas, so that they can stay and work year round and have a path to citizenship – not be indentured through their visa status to their employer.”

El Futuro es Nuestro, which organizes on both sides of the border, has been working to address some of the common violations, including widespread wage theft, farmworkers forced to pay for expensive meal plans and contractors charging exorbitant recruitment fees that can force workers into debt-peonage — a form of forced labor in which a worker is trapped in a workplace in order to pay off a debt. These issues could also plague the meat and dairy industry if granted access to the H-2A program.

As of late, Zavala says they’ve been working to address harassment that H-2A workers have been facing at the border and from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which historically has not been a major concern for workers on this legal visa. She claims that a handful of workers were fingerprinted at the border upon their return to Mexico, without a clear explanation, creating confusion about whether they’d be allowed back into the U.S.

“They’re letting them get back on the bus and go home, but they’re fingerprinting them. They’re not giving them deportation slips. So workers are like, ‘Was I deported?’”

As immigration enforcement expands in North Carolina, some H-2A employers have stopped driving workers into town for weekly trips to Walmart, according to Zavala. In theory, this is to protect H-2A farmworkers and North Carolina farms, but it also results in these workers – who lack their own means of transportation — living even more restricted, isolated lives, moving only between the employer-owned housing sites and their workplaces.

The transition to year-round H-2A visas could take multiple forms. There are a number of bills that have been recently introduced to Congress — the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, the Bracero Program 2.0 and the DIGNIDAD (Dignity) Act — with this provision. This change is also included in an appropriations rider proposed by the Department of Homeland Security, known as the Bipartisan Visa En Bloc amendment, which could pass as part of a government spending bill.

The appropriations rider is the most likely avenue for this change, given that it is part of a larger bill required to pass in order to fund the entire U.S. government, according to Costa.

“The rider still has a long way to go before becoming law and will also depend on whether an omnibus government spending bill is ultimately passed for fiscal year 2026,” wrote Costa, in a recent blog post. “The rider is a statement of intent from legislators who are willing to go to bat for employers seeking new exploitable and underpaid migrant workers to replace their long-term immigrant workers who have been deported or lost status.”

Even as the Trump administration targets H-2A farmworkers, the administration has repeatedly signaled an interest in expanding H-2A recruitment and granting year-long ideas.

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins was directly questioned about her commitment to this expansion in June. “I’m sure you will continue to work with the Secretary of Labor and other members of this administration and the legislature to work towards a year-round dairy farmer visa?” asked John Mannion, a Democratic Representative from New York, during Rollins’s testimony before the House Committee on Agriculture in June of 2025.

“That’s right, and understanding that labor H-2A needs so much work and this committee has done hero’s work on it, but no one is more affected and needs reform more than our dairy industry, and so we’re working very closely and in concert to try to get that done. It is of the utmost priority for me,” said Rollins.

Over the next decade, the Trump administration’s Department of Labor anticipates that the H-2A program will grow from 383,000 certified H-2A worker positions to 502,000 workers.

A broader overhaul of the H-2A program is already underway. The Trump administration has issued a series of policy changes largely geared to making the program easier — and significantly cheaper — for employers to utilize. The most significant change has been a shift in methodology behind calculating H-2A farmworker wages, known as the adverse effect wage rate, which is already in force.

This rule is expected to cut H-2A farmworker wages by between $1.7 billion and $2.1 billion in 2026, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute. This calculation also takes into account a significant change in the H-2A program’s housing. Under the new rule, employers now have the unprecedented right to charge H-2A workers for housing, which was previously provided for free. This could deduct up to 30% of their hourly wages.

In his analysis of the rule, Costa described it as “shocking redistribution of income away from some of the country’s most essential and underpaid workers in order to line the pockets of farm employers.”

This rule will not just lower the wage floor for H-2A workers, but drive down wages for all workers, according to arguments made in a new lawsuit filed by United Farm Workers. Essentially, the adverse effect wage rate — a wage methodology designed to prevent the displacement of U.S. farmworkers with H-2A workers — has often served as a floor for domestic wages. Under federal rules, “U.S. farmworkers that work on the same farm as an H-2A worker need to be paid the same wage at least as the H-2A worker, because they’re considered corresponding workers,” Costa tells Sentient.

However, now that the adverse effect wage rate is lower than the state minimum wage in eight states, this lowers the wage floor for domestic wages too. It’s unclear exactly how employers will respond to this change. “[Domestic] workers don’t usually see their wages reduced on the job, but this could be a case where maybe that’ll happen,” says Costa. Alternatively, he says employers may continue paying domestic workers the same wage, but attempt to phase them out by replacing them with lower-paid H-2A workers.

United Farm Workers argues in the lawsuit that this new wage structure will incentivize the hiring of a “significant number of temporary foreign farmworkers at a wage rate far lower than what U.S. workers would have otherwise received for similar employment” — a move they argue is illegal because it will drive the displacement of domestic farmworkers, undermining this wage system’s original intent.

Greg Schell of Southern Migrant Legal Services also thinks this drastic wage cut will likely prompt an exodus of domestic workers from the farm labor workforce. “I represent a bunch of workers in Mississippi, U.S. citizens who worked for decades. They’re going to drop from $14 an hour to under $9 an hour,” said Schell. “They’re going to leave because they’re going to say ‘I can’t make it on that.”

Yet H-2A farmworkers, who still often make lower wages in their home countries, will likely not have the same incentives and job options drawing them to leave. As a result, Schell projects that the depressed wages will also contribute to the expansion of the H-2A program.

This wage cut was celebrated as an “important step in reform” by the Farm Bureau, the largest lobbying group representing U.S. farmers and ranchers. “Farm Bureau thanks the Trump administration, Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer and Secretary Brooke Rollins for advocating for solutions to a broken system,” wrote Zippy Duvall, the bureau’s president, in a press release. “This new rule holds promise for many farm families who would be out of business if not for the H-2A program.”

These wage cuts could be especially profound in the livestock industry because year-round workers are typically paid more than seasonal farmworkers.

“Jobs in greenhouses, cattle ranching, milking cows, poultry, egg production, hog pig farming — these jobs are some of the ones that pay sometimes a living wage to farmworkers,” says Costa. Yet this will drastically change due to the adverse effect wage cut. “It’s a pretty massive wage cut.”

This wage cut will extend to H-2A workers if they are given entry to year-round industries, and could affect domestic workers, whose wages will be depressed due to the new wage rule.

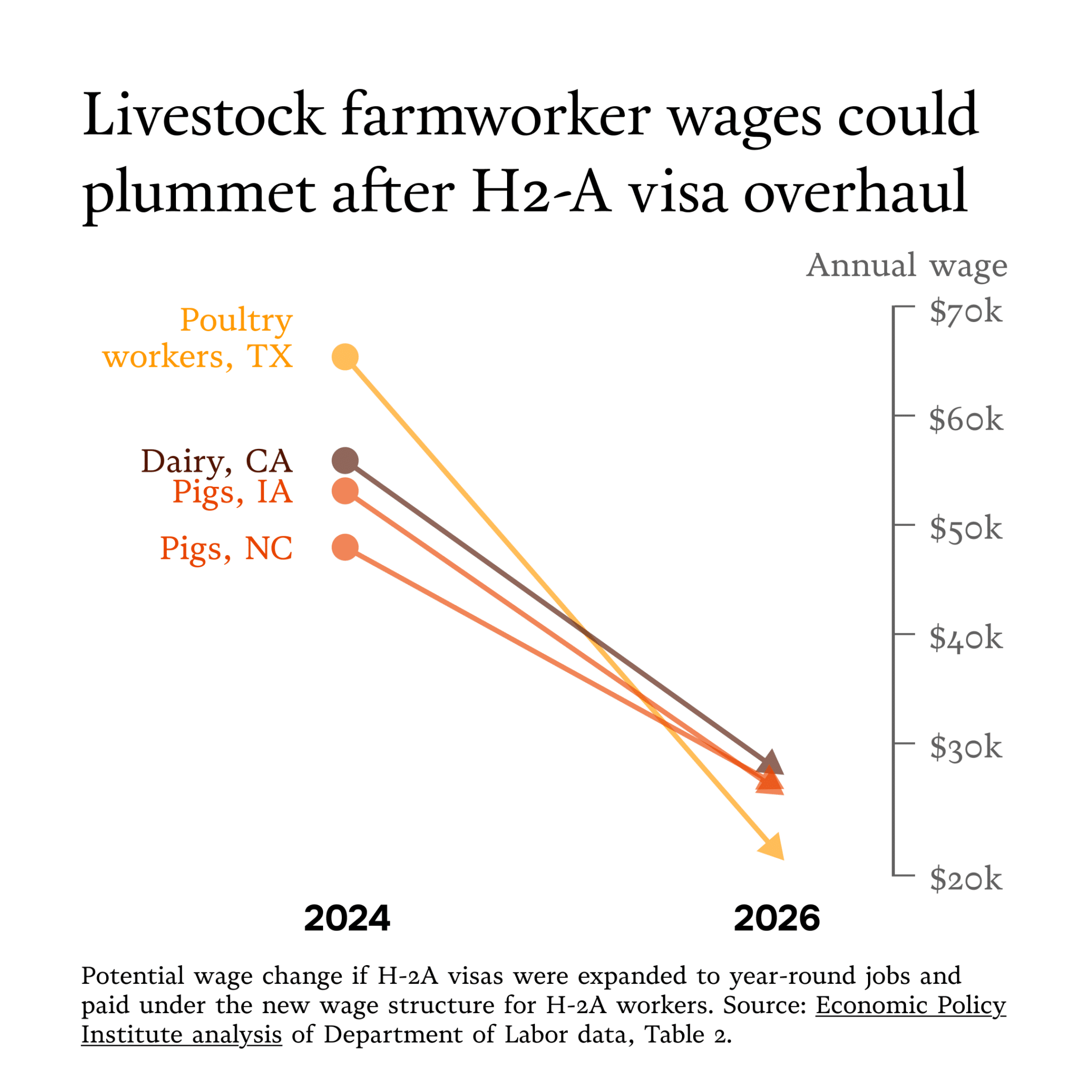

Costa recently conducted an analysis, published by the Economic Policy Institute, looking at the projected wage cut for workers in meat, dairy and other year-round industries if these sectors are permitted to employ H-2A workers under the new wage structure. His calculation includes the sharp deduction of H-2A housing costs.

If the dairy industry moves to H-2A workers, Costa found that California dairy farmworkers would experience an annual wage drop of nearly 50%. The average worker in California on a dairy farm last year earned $56,000, according to Department of Labor statistics. However, if the dairy industry begins to employ H-2A workers, they would earn between $28,900 and $29,000, according to the new wage rates.

Similarly, an average wage drop of $21,000 per year is expected for North Carolina workers on pig farms. The 3,300 workers employed in North Carolina’s hog industry earned an average of around $48,632 in 2025, which could drop to just $27,685. One of the sharpest wage drops, according to Costa’s analysis, will come at the expense of workers in Texas’s poultry and egg industry, whose wages are expected to fall by a staggering $43,641 on average if the industry moves to H-2A workers.

“So really, you can see the kind of money that employers could save if year-round jobs went to H-2A workers,” says Costa. “We’re talking about serious cost savings — bordering on 50% for some of these.”

And it’s a cost savings that would be borne entirely by farmworkers working some of the most dangerous jobs, often without opportunities for upward mobility.

“It’s a terrible situation to bring people into,” says Costa. Increasingly, food will be produced in the U.S. by workers “without workplace rights, political rights for an indefinite period while being vastly underpaid.”