Feature

Stretched Thin, Iowa Agency Issues Few Fines for Manure Pollution

Climate•9 min read

Investigation

Nitrate pollution is straining small water facilities in Iowa, even when they have advanced filtration systems.

Words by Nina B. Elkadi

Residents of Early, Iowa (population 587) say they often find out their water is unsafe to drink by reading about it on Facebook.

On January 27, 2025, the town advised residents that nitrate levels were too high in the tap water and it was unsafe to drink. They noted to especially avoid using the water to mix formula for babies under six months of age. Exposure to too much nitrate can produce the disease methemoglobinemia, which can be fatal in young children — even in concentrations less than the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) limit — and is associated with increased cancer risks.

Two months later, the situation was unresolved. In March, water coming out of faucets in Early contained 11.3 milligrams per liter of nitrate, 1.3 mg/L above the EPA limit for safe drinking water. The town was “working with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources to resolve the situation,” the notice said.

In April, the city’s water still violated the maximum nitrate levels. One resident, who said he has lived in Early since 2017, commented on one of the town’s Facebook posts that this happens every summer.

The issue “should have been addressed long before now,” he wrote.

May and June levels were also too high. According to water department reports reviewed by Sentient, drought conditions caused low water levels in the city’s wells, resulting in increased nitrate concentrations.

Finally, in July, a reprieve. Over 9 inches of rain, which refilled the wells. “All in all a huge improvement,” the water department wrote in the comment section of their July water report. On August 21, the city posted a celebratory message:

“As of August 21st, 2025, Early’s water supply is now clear for drinking and cooking. You may now fully (with some limitations*) utilize your water.” The flyer continued, “You are still required to limit all non-essential uses of water in order to conserve resources.”

The situation in Early is not unique. Four other municipalities in Iowa — Dawson (population 116), Bristow (population 145), Lewis (population 357) and Danbury (population 320) — faced nitrate violations last year.

The water sources for cities like Early have become more polluted with nitrates over the years, largely thanks to runoff from manure or synthetic fertilizer that has been over-applied to agricultural fields.

Excess nitrates are pesky to filter out from drinking water, requiring a pricy reverse osmosis treatment system. Larger municipalities like Des Moines with large water systems can run their multi-million-dollar nitrate removal facilities if levels get too high. Des Moines can also rely on water from backup water sources if nitrate levels are too high in the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers from which the city ordinarily draws its water.

But small towns like Early face tough questions, even with similar technology, like what to provide residents, if anything, when the water is undrinkable, and how to fund fixes for the long term. And drought exacerbates the problem, because nitrate removal systems do not function properly with low water levels.

David Cwiertny, professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Iowa, worries that “we’re kind of teetering dangerously close to having this happen in more and more communities around Iowa.”

“I just don’t think we’re ready for the fallout that comes when you have to tell large segments of your population or entire small communities that you can’t drink your water,” he says.

When Jon Livermore moved to Early five years ago, he did not know the town was having water issues.

He found out pretty quickly.

As he was washing his vehicle, he recalls, a city council member drove by and told him to stop washing, explaining that the city was under a water advisory, posted in City Hall.

When the water levels in wells are too low, there may not be enough water to meet typical household demand. This could also mean there is also not enough water to run reverse osmosis filters, which require a minimum flow of water and pressures to function correctly, Cwiertny explains.

Early Mayor Bill Cougill confirmed to Sentient that one of the city’s wells had very low water levels last year, forcing the city to “divert around” its reverse osmosis filter. This meant the city’s tap water was coming “basically straight out of the ground,” without filtering out the high nitrate levels.

The Early water department’s May water report confirms that the levels were too low for the town to run their reverse osmosis filter. The report, reviewed by Sentient, says the town was “by-passing” its reverse osmosis filtration system because of drought conditions.

As anthropogenic climate change continues to warm and dry out the planet, drought is becoming more common. Nitrate pollution in Iowa, too, is getting worse, according to Iowa Department of Natural Resources data analyzed by the Environmental Working Group.

Livermore knows all too well about nitrates. He is a certified manure applicator, meaning he spends his days spreading nitrogen-filled manure on fields of crops.

The culprit at the heart of nitrate pollution is nitrogen-containing fertilizer, either synthetic or manure-based, applied to corn fields across the state. Iowa is the state with the most factory farms, where animals produce 110 billion pounds of manure that is spread across cropland. Overapplication can saturate fields, causing the pollution to leach into ground and surface water. Some critics of the state’s manure management policies argue that lack of oversight is one reason why the problem continues to worsen.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the median depth for a public-supply water well is 202 feet. One Early well, drilled in 1973, is 33 feet deep. The other, drilled in 2012, is 42 feet deep. Satellite data shows that the wells are surrounded by cropland; indeed, the entire town is surrounded by cropland. As nitrate and other pollutants leach from the surface of fields into the soil, it does not take long for them to reach the wells.

For municipalities like Early, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources administers the Drinking Water State Revolving Loan Fund, which gave out loans totaling $41.9 million in 2025. Early received a $1.45 million loan from this program to dig a new, deeper well. According to Cougill, the town is working toward the planning and designing phase of that project, which the town received a $400,000 loan for.

But these loans will eventually need to be repaid. In towns with only a few hundred people, even with the cost spread across the population, that’s no chump change.

According to the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, the average Iowan pays around $39.20 per 2,000 gallons of water. In Early, that rate is almost doubled when adding in the water improvement fee, which each Early household pays at a monthly rate of $33.25. Cougill tells Sentient that this fee goes toward paying off debt for the new treatment plant, as well as future improvements like a new well. Water costs $31.30 for the first 2,000 gallons (this is also the minimum charge for ratepayers — even if there is a conservation advisory).

These numbers do not include the cost of buying bottled water for consumption during the numerous “Do Not Consume” advisories. In Early, the city relies on donations from local businesses like grocery store Hy-Vee, as well as the state and county government for bottled water, which they typically distribute from 10 a.m.–2 p.m. — a time, Livermore notes, which can be difficult for working families. The posts advise that one household representative can pick up water, which is distributed based on household size.

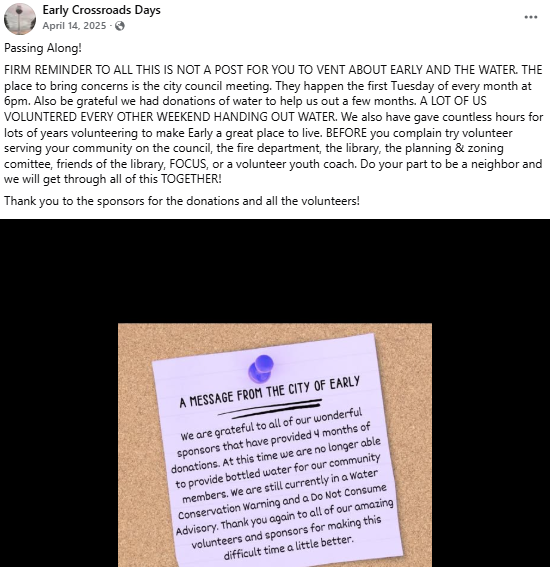

On April 14, 2025, in the midst of the “Do Not Consume” advisories, a notice was posted on the town’s community Facebook page that the town could no longer provide bottled water to their community members.

“We are still currently in a Water Conservation Warning and a Do Not Consume Advisory,” a digital art photo with a sticky note read.

In the body of the post, the author wrote:

“FIRM REMINDER TO ALL THIS IS NOT A POST FOR YOU TO VENT ABOUT EARLY AND THE WATER,” advising residents to voice their concerns at the city council meeting, or volunteer on the council or the fire department, or at the library. “Do your part to be a neighbor and we will get through all of this TOGETHER!”

Early could be a canary in the coal mine for Iowa, Cwiertny says. The water situation in the town is one of “the first of what will probably be many more in the coming years if we don’t find a better way to protect our source water quality, because it’s going to be harder and harder for systems to make it work in a changing climate,” he says.

Protecting the water, he says, must begin at the source of the problem, which in this case, is on fields.

As of right now, Early’s Mayor Cougill says, the town is running their old water filtration system. For now, that’s enough.

“It’s nobody’s fault. It’s just something that happened with ‘Mother Nature,’ and a well going dry,” he says. “We’re having to deal with it, and this is how it has to be dealt with.”

Cougill tells Sentient he does “not even want to speculate” about when the new well will be drilled. It’s a big project, he says.

Livermore does not want to wait. Leaving Early, he says, is the “cheapest” thing to do. “I’m not going to sit here and bang my head against the fucking wall,” he says.

Even when the water is cleared by the city to drink, Livermore explains, it is only a matter of time before the next notice.

“It’s just a whole lot easier just to pack the bags and leave,” he says.

But there is no guarantee the next town will have it all figured out.