Explainer

How Overconsumption Affects the Environment and Health, Explained

Climate•12 min read

Feature

Water resource “hedge funds” and corporate farms are running the desert dry.

Words by Nina B. Elkadi

This far out, there’s no such thing as municipal city water. The afternoon desert sun beats down, hard, as we drive up the gravel road to Tom and Illene Wood’s reddish-brown adobe-style stucco house, nestled off-the-grid within the shrubs and mountains of the Sonoran Desert, with cacti and mastiffs standing guard. Like many residents of rural America, they dug a well. That 400-foot well cost them $10,000. But by 2011, the land had shifted, and they had to dig a new well to the tune of $15,000. Last year, that well ran dry. They’re now on their third well, a $130,000 hit to their retirement funds. Out here, alfalfa might run the aquifers dry.

Tom and Illene have been in La Paz County, Arizona since 1986. We’re sitting in their kitchen, which is adorned with Indigenous artifacts and a wagon repurposed into a bar cart. They built the house in 1998, on a piece of land large enough to also store their small plane and ATVs.

“The water has disappeared, literally, from the area. It just keeps going away,” Illene says. She says she thinks it is because of the alfalfa and other crops being grown in the valley. Her son-in-law and daughter live across the road, and their well also ran dry.

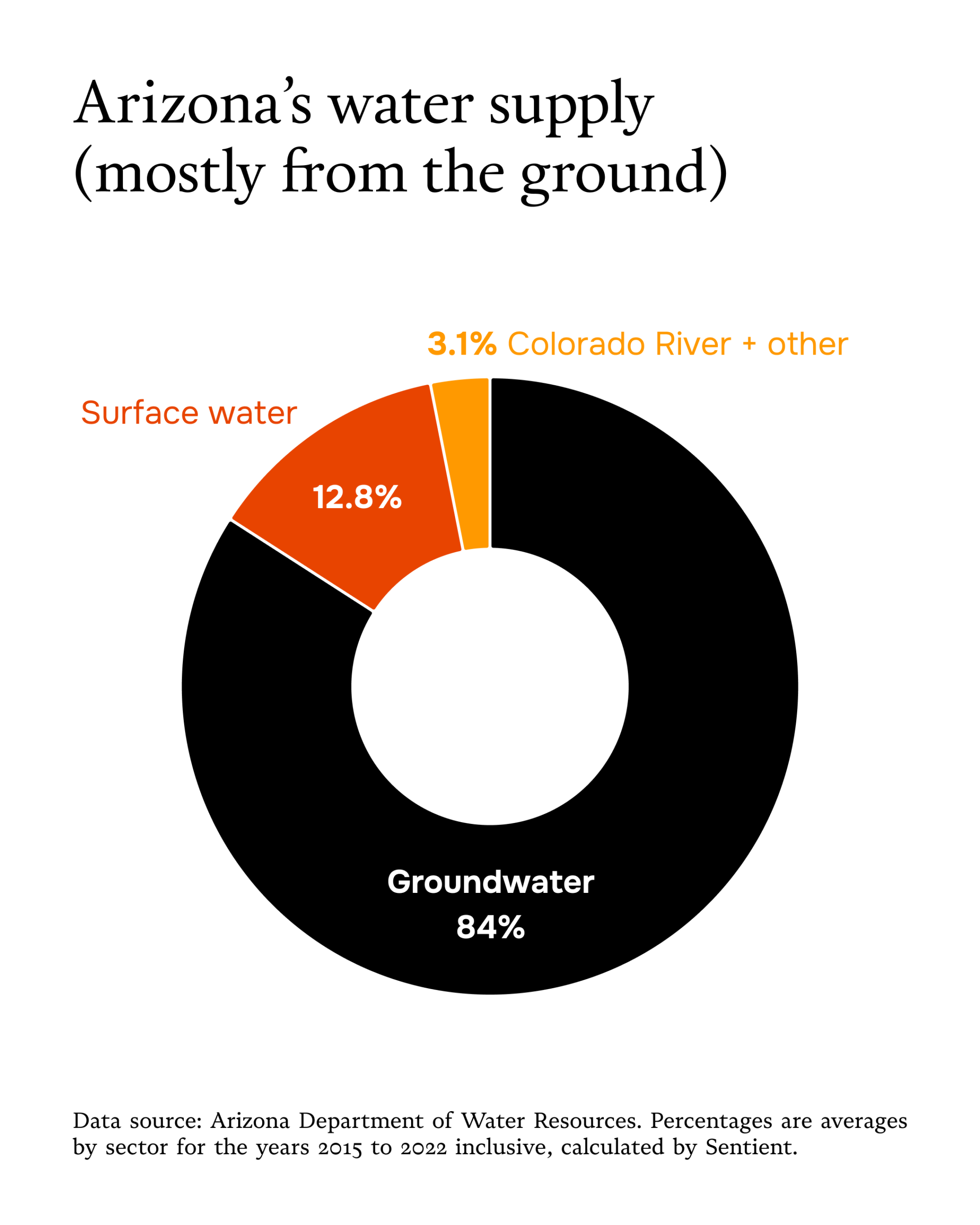

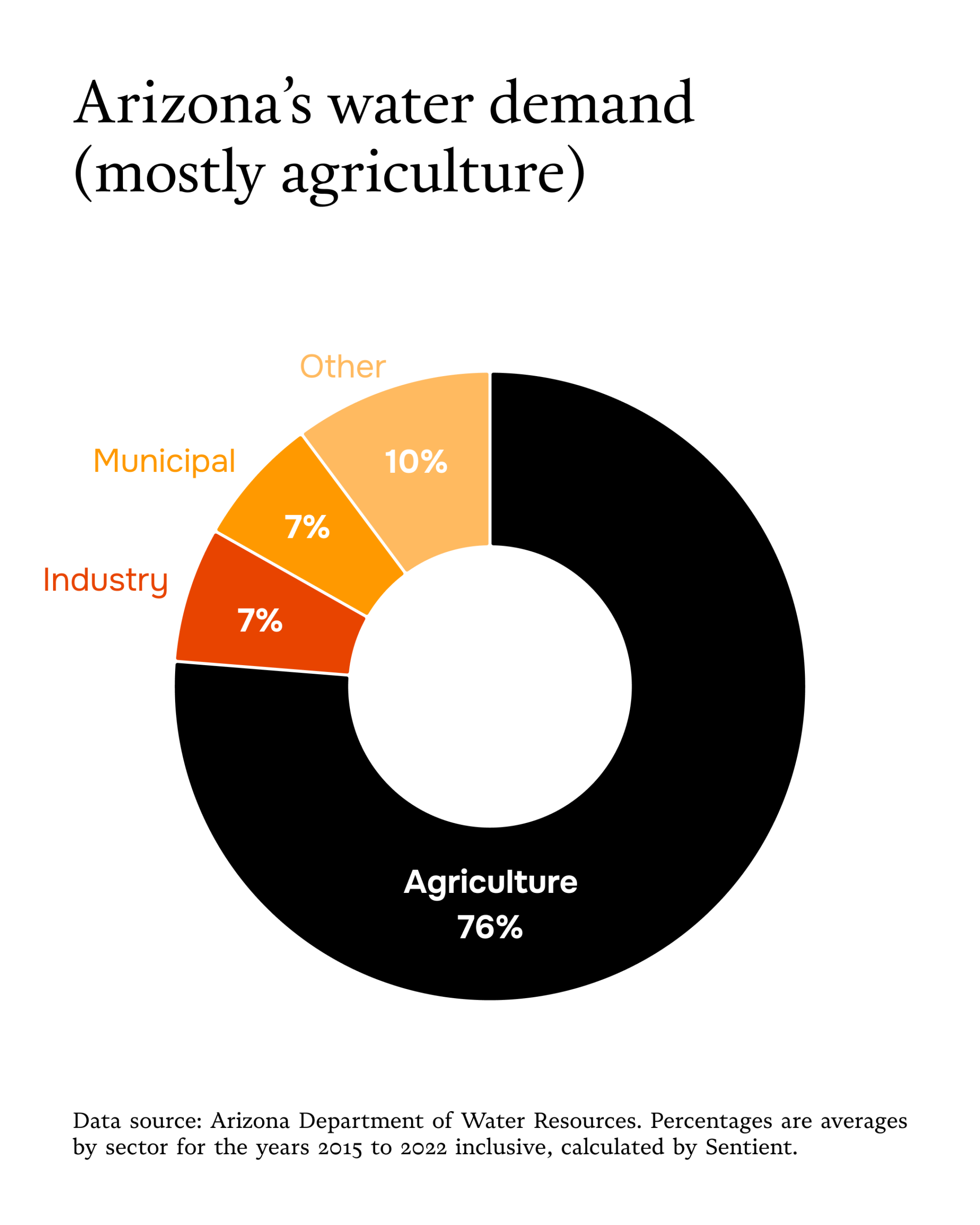

The drive through the Sonoran Desert to the Wood homestead is nothing short of a scene out of an old Western movie — until the alfalfa. The green sticks out like a sore thumb. Miles and miles of it. In Arizona, 76 percent of water use goes toward agriculture. Mature alfalfa (hay) is largely used to feed cattle, and in Arizona, alfalfa is a commonly planted thirsty crop.

A 2020 study found 79 percent of Colorado river water goes to alfalfa, which in turn primarily goes to cattle farms, the most emissions-intensive form of animal farming.

La Paz County, like nearly 80 percent of Arizona, has no limits on groundwater extraction. In theory, this means the Woods can take out as much water as they want each day. But they don’t.

“We’re holding a bucket underneath our water, even with our new well, to save that water,” Illene says. They use the bucket water to water their plants.

Others, though, are not acting quite as neighborly. Outside of certain areas, like Phoenix, if you own the land, you can drill a well and take as much water as you want. And many farms are doing just that. In 2015, the Center for Investigative Reporting did a deep-dive into the Saudi-owned farm drilling deep wells to water alfalfa that they then harvest and ship to Saudi Arabia. The story brought light to a situation that, as time has gone on, is slowly rendering the desert almost unlivable.

Although foreign-owned private farms make-up fewer than one percent of farms in Arizona, the outcome of the extraction, foreign-owned or not, is the same: The big guys, who can keep digging deeper and deeper, are the ones who will survive.

In December 2024, Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes sued Fondomonte LLC, a subsidiary of Saudi-owned dairy company Almarai, which farms alfalfa in La Paz County, citing nuisance due to residents’ wells drying up. Fondomonte asked her office to drop the suit, arguing that the company’s activities are within the bounds of the law.

Almarai did not respond to Sentient’ s request for comment.

“I understand you want to feed your people. I really do,” Illene says, referring to the Saudi-owned operation. “Food and fiber is important to all of us, but so is that water resource, once we lose it, it’s not going to be replaced.”

La Paz County residents and farmers rely on water from aquifers, some of which, once depleted, cannot be replaced. With no limits on the groundwater extraction in their county, the end of water could be near for residents who call this land their home.

“It’s a ticking time bomb,” Jay Famiglietti, Director of Science for the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative at Arizona State University, tells Sentient of the groundwater situation in Arizona.

Although Indigenous people have been farming the region for thousands of years, often rotating corn, squash and beans to maintain soil health in the drought-prone region, settlement and industrialization has changed things. In other words, the level of use has become unsustainable.

Arizona is now home to over 7.5 million people who all rely on water for drinking, bathing and watering their plants. Still, domestic use is a much smaller sliver of water usage compared to that of agriculture, which dominates water use in the state.

“There’s a lot of big straws sucking out the majority of the water,” Famiglietti says. “What I didn’t have the heart to say to residents is, you just spent $100,000 on a new well but you’re probably going to have to spend another $100,000 in a few years.”

La Paz County is far from a place where the average resident can spend $100,000 for water. The median household income in the community of 16,000 people is just above $49,000. The average property value, at $117,600, sits thousands of dollars below what the Woods paid for their latest well.

Most of the groundwater is 20,000 years old, stored in aquifers deep below the soil. This water is often referred to as fossil groundwater because it cannot be recharged quickly by rain. If the water is used faster than it can be replaced, eventually it will be gone. An aquifer is like a sponge. If you squeeze it too hard and too often, it gets compressed and can’t soak up water the same way again. But if you let it rest, it can slowly refill. A well-treated sponge can bounce back. An over-crushed sponge, once fully squashed, may stay that way forever.

Holly Irwin, La Paz County Supervisor, meets us at a church right on the edge of the Vicksburg Fondomonte operation, donning cowboy boots and driving her government-issued car. The church’s well ran dry years ago, she says. Both sides of the road are green with un-harvested hay. Hay trucks with empty beds blast past us, ready to be loaded. The noise is deafening.

“It’s freaking all day. It’s literally all day,” she says.

Holly has calculated the rate the Fondomonte wells have the potential to extract water at 64,000 gallons per minute. A typical washer uses 20-25 gallons per load. According to Mayes’s lawsuit, “In 2023 alone, Fondomonte used approximately 31,196 acre-feet of groundwater within the Ranegras Basin, constituting over 81% of all groundwater extracted in the Ranegras Basin that year … A single acre-foot of water can supply water to three single-family homes for an entire year.” As county supervisor, Irwin is concerned about the future of her county and its ability to attract new residents.

“There’s no restrictions, there’s no monitoring, there’s no anything and it’s definitely a concern for our people,” she says. “The way that the law is, if you live here, you own land, and you’re allowed to use that water. You can pump and pump and pump.”

In 1980, Arizona passed the Groundwater Management Act, which established extraction limits in less than a quarter of the land in the state. La Paz County was not one of them. In this part of Arizona, Irwin says, the “mom-and-pops” aren’t here anymore. The big guys are the ones who have been able to survive.

Vicksburg Road, which we are standing on the side of, is surrounded by alfalfa on both sides.

“It’s cost us so much money just to do the repairs on these roads because of the influx in trucks that are used,” she says. She estimates those repairs have cost $2.4 million. Fondmonte moved into Vicksburg in 2014, to a humble $48 million 10,000 acre plot.

Four years later, Saudi Arabia banned alfalfa growing in the country due to water scarcity concerns. Since then they’ve outsourced: They grow their alfalfa in Arizona and ship the hay to Saudi Arabia to feed cattle. Saudi Arabia is planning to build a multi-billion dollar “livestock city” project to meet growing demands for meat in the county.

Water resource “hedge fund” groups — investors who buy and sell water resources — also see opportunity in La Paz County, though not in the way Irwin would hope. They’re buying up land — in a recent case, $100 million worth, all in cash.

Fondomonte was not the first to farm that land, nor will they likely be the last. Google Earth data shows that specific area in production since at least 1985. In the early 1980s, alfalfa farming in Arizona increased from 25,000 acres to 45,000 by 1997. Today, in La Paz County there are about 65,000 acres in production for alfalfa, an area roughly the size of Washington, D.C.

On our way to an alfalfa operation in Wenden, Irwin pulls off to the side of the road. She wants to show us a canal for the Central Arizona Project, a Colorado River diversion which provides water to three areas in Arizona: Phoenix, Pinal and Tucson.

We stand up against the fence and stare at the water reflecting the cloudless blue sky. And La Paz cannot touch it. Just because you can see the water does not mean it’s yours.

They might be able to access the groundwater, however, if she can persuade lawmakers. Groundwater in Arizona is currently only regulated in Active Management Areas, that quarter of the state governed by different laws. In those areas, the laws require developers to demonstrate 100 years of available water for any new subdivisions. Additionally, real estate agents must inform buyers about the current water situation in their area.

Even areas with those requirements are not meeting their goals to safely replenish groundwater, Famiglietti says. If anything, the Arizona Republic reports, they are moving further away. The other option would be to regulate the region as an Irrigation Non-Expansion Area, which limits the expansion of irrigated land.

Irwin has been advocating for a different type of regulation altogether, which might give her residents more flexibility. She wants something made for rural communities, something that would give local authorities more control. One bi-partisan bill, the Rural Groundwater Act, could be just that. Irwin, a Republican, was alongside Democratic Governor Katie Hobbs when Hobbs introduced the legislation at a press conference.

Because as it stands now, Irwin is stuck.

“That’s one thing that’s been very frustrating, is the county can’t just come in and say, ‘we’re going to start regulating your water level,’” she says. “We don’t have the tools to do that.”

In March, Famiglietti was out in La Paz County, meeting with residents about the water scarcity issue. Despite how worried residents are, many were unaware of the connection between large-scale agriculture and water scarcity.

“Everyone was there because they were really concerned. And some knew more than others, but some people knew nothing, and that’s scary,” he says. Depleting the region is not inevitable, he says. “It’s 100 percent caused by these big farms.”

Proponents for growing alfalfa in the desert say the economics make sense — you can get a high number of alfalfa cuttings per year in the desert, you can control your inputs (like water) and the weather is predictable. One of the missing links these advocates often fail to note is that the alfalfa is going to feed cows, not people.

“Dietary changes are something we don’t really talk a lot about,” Famiglietti says. “If we moved away from meat and dairy, we’d be in much, much better shape.”

As far as household actions go, shifting to a plant-forward diet is one of the most effective things an individual can do for the climate. Famiglietti notes that aside from their need for food, cows contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and are a large factor in accelerating climate change.

Cutting back could have other carbon benefits when coupled with rewilding, reverting pastureland back to forest and other wild landscapes. Restoring land to its uncultivated state helps keep carbon emissions out of the atmosphere. It could also mean a chance for the aquifers in La Paz to recharge.

At a store off highway 60, I’m told not to listen to the folks trying to convince me that there’s a water issue in La Paz county. “It’s all political,” the clerk says. They explain that the water issue is not real — they have not had any issues with their water, anyway.

Where do they get their water?

The Wenden Domestic Water Improvement District.

When the Wood’s well ran dry the second time, there was a saving grace: Gary Saiter at Wenden Domestic Water Improvement District.

“Thank goodness for Wenden water,” Illene says. She called Gary up and he told them to bring their trailer over to haul water. It was pay-as-you-go. Tom would head into Wenden, get a load, and come back. Illene explains that Tom is hauling water for their son-in-law and daughter now — their well has run dry and it is too expensive to dig a new one.

“They’re putting in a storage tank, and we’ll keep hauling water for them,” Illene says.

Later that afternoon we meet Gary at the Wenden Domestic Water Department. He’s sitting at a table in the middle of the room, a folder of documents and fact sheets ready to go. He offers us — twice, maybe three times — leftovers from a catered lunch and cookies.

Gary is the chairman of the board for the water department and the general manager. He’s also president of the school board and serves on the board of adjustments and appeals for the county. He’s also a part time accountant for his wife’s business and a semi-retired Sherwin-Williams executive. He also plays guitar.

In 2004, Gary visited his father and stepmother who were celebrating Christmas in Salome.

“Behind the sandwich counter was this little, short, gorgeous woman, and that was December 22, 2004 at 12:35 in the afternoon,” he says. “My life’s never been the same.”

Wenden is four feet lower than when he moved here. The ground has literally sunk. As an aquifer drains, and does not recharge, it’s like pulling the stuffing out of a mattress.

“That’s because of subsidence,” he says, referring to the phenomenon of sinking or settling land, “because of over-pumping groundwater,” he says. His wife, DeVona, owns a store across the street. The ground there has shifted so much you can see it slope when you walk in.

When he first moved to La Paz County full-time in 2008, at least some of the farms were “growing people-food.” Now, mono-crop alfalfa farms landlock Wenden. Saiter calls it an “alfalfa valley.”

The recent $100 million hedge fund land purchase occurred in Gary’s home turf of Wenden. He starts telling me all about the asset management company, and its shell company, and what their plans could be for the water: Including potentially pumping and sending it to Phoenix. I ask him how he knows all this.

“I’m responsible for the things that happen in Wenden. I’m specifically responsible for water and the future of our water. If something happens that impacts it either positively or negatively, I feel it’s my responsibility to know,” he says. “It’s my valley, my home. And too many people wait until something sneaks up on them and then they find out.”

Wenden Domestic Water Department provides a service unlike any other in the region. It services water directly to homes. There are 242 connections, which translates to roughly 450 customers in town. There are also some bulk water buyers, like the Woods were.

“The only reason to keep us here and to keep us alive is to have water, and if that’s gone, this reverts to desert,” he says.

Gary tells us that people on Wenden Domestic Water aren’t just paying for the service. They are paying for something almost unheard of when it comes to water here: peace of mind. Someone else to do the thinking.

“In 1946, right where I’m sitting, the water table was 117 feet. Today it’s 540 feet. So as a private individual, to get a well that’s going to work, I not only have to go down to where the water is, I have to go below that, because I have to ensure that my pump and motor stay submerged,” he says.

The water department has the benefit of ratepayers, which means pooled funds, which allows them to afford digging as deep as the Big Ag players. Wenden has two wells, each 1,500 feet deep. Still, if extraction from the big players continues at the same rate, eventually even Wenden won’t have water.

“In order to get this in balance, we need to reduce the water usage by 80 percent,” he says. “There’s only one way to do that. Stop farming. Otherwise, people will leave because they won’t have water.”

Living off the grid isn’t so easy when your neighbors are running your only source of water dry.

Still, La Paz is attracting desert-craving retirees to its RV parks and barren landscapes. J’aime Morgaine is one of them. We meet her and her friend at Silly Al’s pizza in Quartzsite. She’s in the process of permanently moving down to the county, a gamble, she knows, because she has studied the water tables. In fact, she’s a self-described “water warrior.”

“We’re going to run out of water,” she says. “What’s going to happen to the property value? Maybe if you’re a snowbird in the north, you can go somewhere else, but there are people who have invested everything they have to live here. And those people have a right to have security in their livelihood as well.”

She is moving to La Paz, in-part, because she saw a political opportunity.

“I sold my property and bought a 17-foot trailer, and relocated down here so that I could establish residency and organize the county Democratic party,” she says. The trailer gives her the chance to “move where the water is” if need be.

She doesn’t hold a grudge against Fondomonte for coming into Arizona to make a living — a refrain we hear from the Tom and Illene Wood, too. But she wants a water strategy that will benefit “everyone,” not just “corporate industries.” Something that requires teamwork, and perhaps compromise.

“Not just me first, or, Salome first, or Arizona first, or whatever first,” she says. “We need to understand that if we’re all going to get through this, we need to get through it together.”

We drive to her new home, a trailer parked at an RV park in Brenda. In this remote desert community, Morgaine has chosen to be neighbors with her best friend. Along with the rest of the RV park, they’ll share a well.

She’ll spend her retirement enjoying the desert landscape and fighting to maintain the one resource necessary to stay.