Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Solutions

In the struggling lab-grown meat sector, the companies that remain are getting creative.

Words by Dawn Attride

Ines Lizaur has spent her career vying to turn failures into success. At SpaceX, she worked on perfecting Falcon rocket reliability systems and at BMW, she solved hardware challenges in high-volume car production. Now, she’s involved in a more flavorful challenge: working to launch lab-grown meat at scale. “A lot of the same lessons apply,” she says, of her time working in aerospace and now food.

Lizaur is the Chief Technology Officer at Vow, an Australian cultivated meat company that has leaned into the unconventional nature of their products — creating rare delicacies like Japanese quail foie gras along with the downright wacky, like their woolly mammoth meatball. Lizaur and the rest of the Vow team are hoping their creative approach and ambition to scale will help them succeed — and serve as a glimmer of hope in an industry that has struggled in recent years to survive.

Proponents maintain that cultivated meat — meat grown from cells — is one of the few solutions to our meat consumption problem that can win over meat eaters. Still, the industry has plenty of skeptics, including Marion Nestle, Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, Emerita, at NYU. “Bringing production to scale, reducing the price to something acceptable and convincing consumers to want to eat these products,” are the major challenges facing the industry, Nestle told Sentient in an email. Yet if these challenges can be overcome, cultivated meat would be a path for reducing the many impacts of the meat industry — including greenhouse gas emissions and billions of animals slaughtered each year.

Getting the texture and production costs right remains a time-consuming and costly process, a challenge that has left some cultivated meat startups with no other option but to shut down. Those still standing, like Vow, Wildtype and Upside Foods, have had to be nimble in their approach to attract millions of dollars of investment, in the latter two cases from large meat companies like Cargill and Tyson. To add yet another challenge: seven U.S. states have banned the sale of cultivated meat.

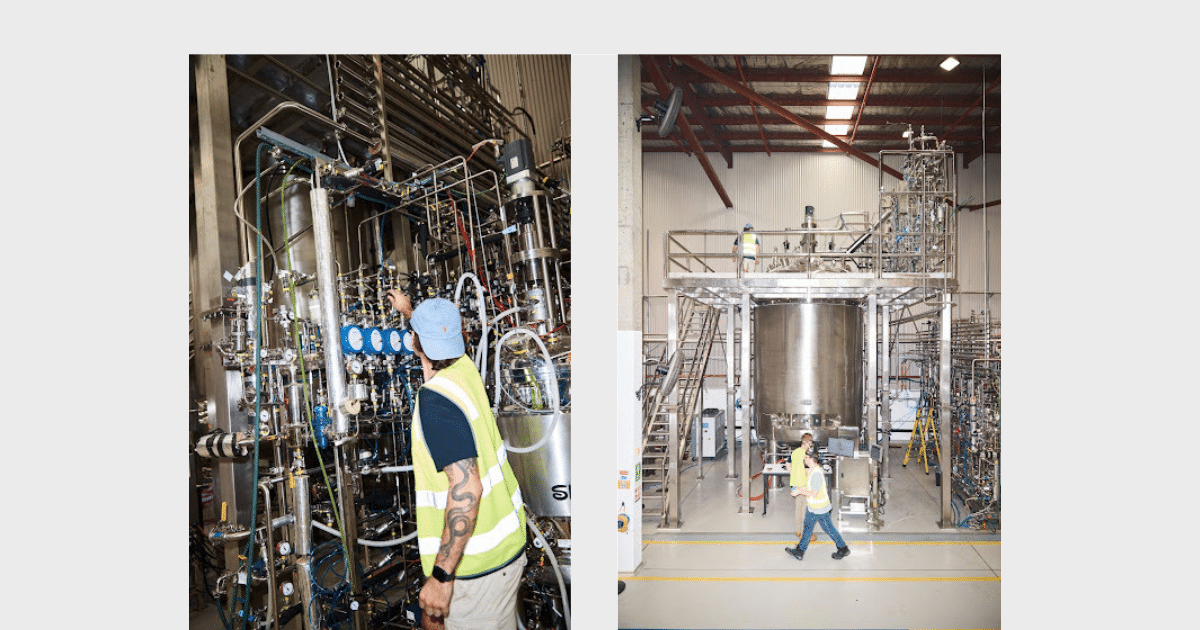

In Vow’s commercial facility in Sydney, lab-grown meat production takes place in a series of stainless steel tanks. “It doesn’t look too dissimilar from a rocket production factory or a brewery,” Lizaur tells Sentient. The process starts by selecting the perfect cells, similar to “choosing the best seeds for a harvest.”

Growing conditions in the reactor need to replicate the body of the animal, in both temperature and available nutrients, like amino acids and sugar. When the cells are ready for harvest, technicians separate out the meat cells from the broth, much like skimming curds from whey in the cheesemaking process. From start to finish, creating the pink-sheened Japanese quail foie gras, or “forged gras,” takes 79 days. In Singapore, dishes featuring around an ounce of meat, more or less, retail for between $12 and $32.

Scaling up production to compete with conventional meat still remains out of reach for most companies in the sector. Vow says they have been able to scale their products thanks to their 20,000 liter culture reactor that cost under a million dollars. This food-grade cell culture reactor is the “largest in the world,” able to produce a “record” harvest of over 2,000 pounds as of June. Nestle says she gives them “a lot of credit for managing this.”

A critical component of good bioreactor design is adopting a first principles approach, Claire Bomkamp, senior lead scientist at The Good Food Institute (GFI), tells Sentient. “There’s this broader need to design equipment that’s a lot more fit for purpose, rather than taking something off the shelf that’s been designed more for the needs of pharma.”

David Kaplan, director of the Tufts University Center for Cellular Agriculture, sounds a cautious note. “This is a great step,” he tells Sentient of the 20,000 liter reactor, “but it’s still what I would call a drop in the bucket compared to the scales we’re going to eventually need to get to.”

While Vow appears to be light years ahead on tackling the scale problem, they currently only have regulatory approval in Singapore, Australia and New Zealand.

In the United States, companies are subject to approval from the Food and Drug Administration before they can roll out their products commercially. Wildtype, a San Francisco-based cultivated seafood company is the latest to receive FDA approval, and has started rolling out their sushi-grade salmon as an appetizer served at Kann, an award-winning restaurant in Portland, Oregon, ringing in at $32 for one to two ounces of fish.

Only four lab-grown meat companies currently have approval in the United States. The process can be a time-consuming one –– it took Wildtype a little over three years.

Wildtype’s salmon cells came from a Coho salmon in Washington State and are fed a nutrient-rich mix of vitamins, proteins and fats, “not unlike Gatorade,” Justin Kolbeck, co-founder and CEO of Wildtype, tells Sentient. The process takes about two weeks, which is considerably shorter than growing an actual fish, he points out.

Many fish populations, including some Coho salmon, are endangered, a problem that Wildtype hopes it can help address. Wildtype’s mission is to “defend Earth’s wild places by inspiring a transition to clean and accessible seafood.” The company has partnered with conservationists to protect 44,000 acres of salmon habitat in Alaska. For now, their pilot facility in San Francisco can currently service up to roughly 50 restaurants, and they too want to be prudent about scale.

“The intent for this facility is to learn and to make manufacturing mistakes at lower cost, lower scale, rather than big scale, super expensive facilities,” Kolbeck says. “It’s not trivial to build a piece of salmon from the cell up. And so we’ve done the best we can with the time and the talent that we have, but now we’re getting real feedback from the market, and we want to be able to incorporate that as nimbly as possible.”

Cultivated seafood is particularly complex to create, mainly because the existing research isn’t as substantial as it is for cultivated meat, like pork or beef, GFI’s Bomkamp says. “We’re really excited at GFI about these sorts of advances that individual companies are making,” she says. But one area where more open access research is needed is around the challenges to scaling up production, Bombkamp says, including both barriers and cost drivers.

At Kaplan’s lab at Tufts, he tries to address these problems in his research, as well as improve the texture and nutritional content of cultivated meat, in part thanks to a $10 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While growing the muscle cells is the main component of lab-grown meat, other factors like fat help to replicate a realistic texture and taste, which his lab pioneered work on.

Another critical area of research is figuring out future energy requirements. A 2024 University of California Davis study found that lab-grown meat might be worse for the climate than beef due to the large quantities of energy needed. But a study by GFI found pretty much the opposite: the carbon footprint was lower than that of beef, and cultivated meat would be significantly better for the environment in terms of land use.

The UC Davis study attracted a lot of media attention at the time, as well as criticism from many proponents of cultivated meat. In an email to Sentient about the study, Bomkamp wrote that there were “a number of assumptions made…that differ from others in the field, including ours. The most questionable of those is probably the use of pharma-grade purification for the media, which (at least as they model it) substantially increases the environmental impacts.”

In GFI’s research, switching to renewable energy to power cultivated meat production resulted in lower emissions than both beef and pork, and equivalent to chicken.

Ultimately, researchers are unable to pinpoint the exact amount of future emissions because we’re not currently at scale, Kaplan says. Still, Kaplan feels the evaluations of sustainability overall suggest cultivated meat will be better than conventionally produced meat, but it’s not yet clear “how much better,” he adds.

Sourcing from clean energy will undoubtedly be critical. “Using decarbonized energy sources like solar and wind is very crucial for cultivated meat to live up to this potential,” Bomkamp says.

Despite cultivated meat’s skeptics, the sector’s researchers and companies press forward, trying to remain optimistic.

At Tufts’ Center for Cellular Agriculture, Kaplan’s hope for cultivated meat’s future is a tailored experience for consumers. “My vision is…ten years from now, you’re going to go to the supermarket, and you’ll have a choice,” whether that be cultivated, plant-based or meat from livestock. “People will make their own decision based on many factors,” he says. And whether the choice is driven by flavor or nutrition, he adds, “my goal is to make those factors more and more compelling.”

By the end of the year, Vow says they’ll be able to scale to 50 times their previous capacity. The Australian company says it’s on track to improve its economic baseline too — aiming to make more money per unit than the cost of production. For Wildtype, they’re focused on honing taste and texture.

Lizaur sees the future of lab-grown meat as another problem to solve. “There’s a lot of problems that we need to solve as an industry in order to scale up, drive costs down and achieve consumer acceptance.” But she’s not deterred. “The most exciting thinking and problem-solving happens when you’re kind of at that cusp.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Vow would soon have regulatory approval in New Zealand, when it currently has it in Australia and New Zealand, as well as Singapore.