News

Ten Million Tons of Manure In California Are Unaccounted for, New Report Shows

Climate•11 min read

Reported

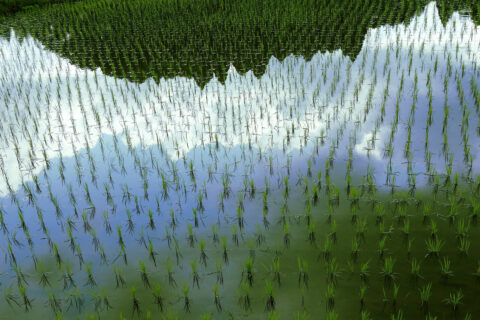

Farmers are focusing on ways to reduce methane emissions and save water to further reduce the staple crop’s climate footprint.

Words by Lisa Held

Rice may be having a moment. Until recently, the average American ate only about a half a pound of the grain annually, while people in some Asian countries eat upwards of eight pounds a year. By early March, however, one data firm found that sales of rice and other staples were up 84 percent. And, as significant questions have arisen about the short-term future of meat production, this grain could become a more significant part of the U.S. diet.

As one of only a few commodities grown in the U.S. that go directly to feed people, rice also has a much smaller environmental footprint than many other foods.

“People underestimate rice. It’s a small grain,” says Meryl Kennedy, who is the daughter of a Louisiana rice farmer, the CEO of Kennedy Rice Mill, and the founder of 4Sisters Rice. During a pandemic, however, it can feed a lot of people efficiently.

But rice farming isn’t perfect. In fact, global rice production accounts for at least 10 percent of agricultural emissions. It’s responsible for producing large quantities of methane—a greenhouse gas that’s 24 times more potent than carbon dioxide. But, as it turns out, that’s more a factor of quantity than it is about growing method. Rice provides one fifth of the world’s calories, and research shows that, per calorie, it actually has one of the lowest emissions footprints compared to meat, fruit, vegetables, wheat, and corn.

Now, there is growing attention to practices that further reduce the climate impact of rice. And, given that it is the fourth largest crop grown in the world, those changes could amount to a significant climate solution.

In the 2020 Drawdown Review, which analyzes the impact of various climate solutions across industries using the latest scientific research, the nonprofit thinktank Project Drawdown includes two methods of shifting rice production.

“Both of these solutions are about how you can grow rice most sustainably. This is a shift from conventional to an improved way of rice cultivation,” said Dr. Mamta Mahra, a senior fellow at Drawdown in biosequestration modeling. “The point is: If we’re already growing rice, why not see how much emissions can be reduced?”

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), rice is the fourth largest crop in the world. If adjusted to account for how much is eaten by people, it would probably rise in the ranks, since corn and sugarcane are both also used to produce biofuels.

China’s farmers far and away grow the most. The U.S. ranks twelfth in global rice production, and the vast majority happens in six states: Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas. In 2019, American rice farmers harvested about 18 billion pounds of rice from just under 2.5 million acres. About half of that rice is exported, primarily to Mexico, Central America, and Northeast Asia, to feed global appetites that are bigger than those in the U.S.

“The U.S. produces more rice than we eat,” said Kennedy. “I hope that that changes in my lifetime.”

What is gradually changing is how the industry is thinking and talking about its environmental impact. Last year, USA Rice, which represents the industry, published a 64-page sustainability report. And this week, it announced new sustainability goals, pledging to reduce both water use and greenhouse gas emissions by 13 percent by 2030.

Most rice in the U.S. is produced on thousands of acres that are flooded for the entire season. Flooding controls weeds and serves other purposes, like making nutrients in the soil available to the plant. But it requires a lot of water, and microbes that live in the soil beneath flooded fields produce methane, which is then released by the plants.

Reducing the amount of time that fields are flooded, then, serves two purposes: conserving water and reducing emissions. That’s one of the primary practices involved in what Project Drawdown classifies as “improved rice production.”

In the Southern U.S., a growing number of farmers are using a method called alternate wetting and drying (AWD). Studies have found that depending on how often and for how long farmers drain their fields, the practice can reduce methane emissions by as much as 65 or even 90 percent. AWD is not widespread, though, and it’s not yet clear how it affects yields.

Kennedy said other methods of water conservation like furrow irrigation (also called row rice) and tailwater recovery, which allows farmers to reuse water multiple times, are more popular.

There is also evidence that some rice farmers are tilling their soil less, another approach that reduces emissions. According to USA Rice’s report, a study out of Louisiana found that the number of rice farmers using low- or no-till methods increased from 26 to 41 percent between 2000 and 2011.

Breeding new strains of rice can also help farmers implement these practices and has the potential to directly reduce emissions. Anna McClung has been researching rice varieties since 1991 and is the director of the U. S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center in Arkansas.

Her team uses a sophisticated form of traditional breeding that tracks existing genes within plants. Researchers in other countries have used genetic modification to modify rice for resistance to climate change, but there is currently no GMO rice approved for production in the U.S.

“Our current research plan is 80 percent focused on … climate change,” McClung told Civil Eats. Drought and extreme heat threaten rice crops, and her team is looking at traits and varieties that can withstand those conditions while supporting new farming methods. “Water is being used to control weeds, but it also provides this uniform growing environment so the plant can do its best,” she explained. “If you go to a system where you’re not keeping the field flooded, but all of your varieties have been optimized for flooding, that’s not going to work.”

McClung’s team has also compared methane is production based on the variety of rice grown. “We saw big differences in the amount of methane. Rondo has about 2.5 times the methane released as the next variety, Jupiter. And about 5 times the methane released as the other three rice cultivars,” she said. “The question is: why?” More research on that front may yield discoveries that allow farmers to plant low-methane rice varieties.

More growers are choosing to grow rice using organic practices. USDA data show a 5,000-acre increase between 2008 and 2016, and USA Rice’s report says organic production has “increased six fold in the past 20 years.” But there is little research on how organic systems compare in terms of emissions.

At Lundberg Family Farms in California, Bryce Lundberg’s parents were growing organic rice before there was a national organic standard. His family started milling its own rice in 1969, and he started farming with his brother in 1985. Today, the family grows about half of the rice they sell and sources the rest from other farmers, the vast majority of whom are nearby.

Eighty percent of the rice they sell is organic; the rest meets a standard they call eco-farmed. “There’s no burning of rice straw, there’s a requirement for rotation. There’s only one insecticide approved…and several herbicides, but none of them can be in the danger [category],” he said. “It can’t be a carcinogen. It can’t be a mutagen. It can’t be on PAN’s ‘bad actor’ list. It can’t be a broad-based killer that would affect frogs, snakes, fish. It can’t persist in water.”

The approach his parents took, he adds, was based on their “wanting to work closely with nature, and not poison the place where they farm or the place where they live.”

On organic rice farms, skipping synthetic fertilizers and herbicides (which are widespread in conventional rice farming) is a strategy that can result in healthier soil, which may hold more carbon. Without weed killers, however, flooding becomes even more important. Lundberg controls weeds by flooding fields to kill grasses and then drying fields out for months to kill aquatic weeds. The system ends up looking like a version of AWD, and Lundberg said U.C. Davis has been working with the company on research that shows it does reduce methane emissions because the plants and soil spend less time immersed in water. They hope to release the study by the end of this year.

To Norman Uphoff, all of these improvements are small compared to the benefits of a revolutionary system called System of Rice Intensification (SRI).

Uphoff is the senior advisor for SRI-Rice, an international network and resource center out of Cornell University, where he has taught since 1970. SRI was developed in Madagascar in the 1990s as a method for smallholder farmers to feed themselves using fewer resources.

Unlike in conventional systems which involves “broadcasting” seeds (basically, dropping them from a plane) all over a flooded field, farmers using the SRI system plant rice seedlings in a grid pattern in dry soil, with space between them. They spread compost to build soil health (although some also use synthetic fertilizers) and then use an alternating wet-dry irrigation system instead of flooded fields. They control weeds with rotary weeders or by hand, rather than use herbicides.

“The plant will grow to fill available space,” Uphoff explains. “If the roots can grow freely, with not too much water and enough organic matter, you get more root growth and more tiller growth.” Tillers are like the branches of the plant; when there are more of them, each plant can produce more rice.

A number of studies over the years have shown SRI can produce high yields—usually from 20 to 50 percent higher—compared to traditional flooded paddy systems, while saving money on inputs. A meta-analysis done in 2013 found SRI management resulted in 22 percent less water use. Several studies have also shown that SRI leads to significant reductions in methane emissions, and while it does increase emissions of nitrous oxide, another powerful greenhouse gas, the net greenhouse effect is still positive.

Uphoff said farmers in 60 countries are using SRI today, with about 20 countries leading the charge. “We estimate that at least 20 million farmers are using these ideas in full or in part—enough so that they’re getting improvements in their crop performance,” he said. Most U.S. farmers, however, have shied away from the practice.

“Our primary concern has been for farmers in poor countries. U.S. rice production is highly capitalized and subsidized,” he explained. The idea of cutting a plant population by 80 or 90 percent, isn’t likely to be popular here, he adds. “The people who make their livelihood on…seeds, fertilizers, and herbicides don’t want to hear about this.”

There are a few examples of small American farms using some of SRI’s principles to grow “dryland” rice. Blue Moon Acres in New Jersey is well known in the Northeast, and Next Step Produce and Purple Mountain Organics are pioneering their own processes in the Mid-Atlantic. California-based Lotus Foods also sells rice produced by smallholder farmers around the world using SRI.

But for the vast majority of rice production—which is large-scale—sources said farmers brush SRI off as impractical, especially because it tends to be labor-intensive. Uphoff said the missing piece is specialized equipment, and if that mechanization existed, there would be no reason not to apply it on a larger scale.

Project Drawdown, for its part, presents the two approaches—promoting SRI among smallholder farmers around the world while using other techniques on large-scale farms—as complementary solutions with real potential. In other words, with so much rice in the world and a rapidly changing climate, all efforts to shrink this important grain’s footprint are worth the effort.