Explainer

Your Thanksgiving Meal’s Climate Impact, in 4 Charts

Climate•4 min read

Investigation

“Off spec” liquid from Winston Weaver fertilizer fire that was applied on a nearby farm field contained toxic PFAS.

Words by Lisa Sorg, Inside Climate News

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C.—Perhaps it was rain dripping through one of the many holes in the roof that condensed the ammonium nitrate into a potentially explosive cake.

Or maybe it was an electrical short, like the one that had occurred a month earlier, igniting a pile of fertilizer.

Regardless of the cause, on the evening of Jan. 31, 2022, the Winston Weaver fertilizer plant caught fire.

For the first two hours of a week-long siege, Winston-Salem firefighters inundated the plant with more than a half million gallons of water as they furiously tried to prevent 600 tons of ammonium nitrate—stored in wooden buildings and a rail car near a residential area—from exploding.

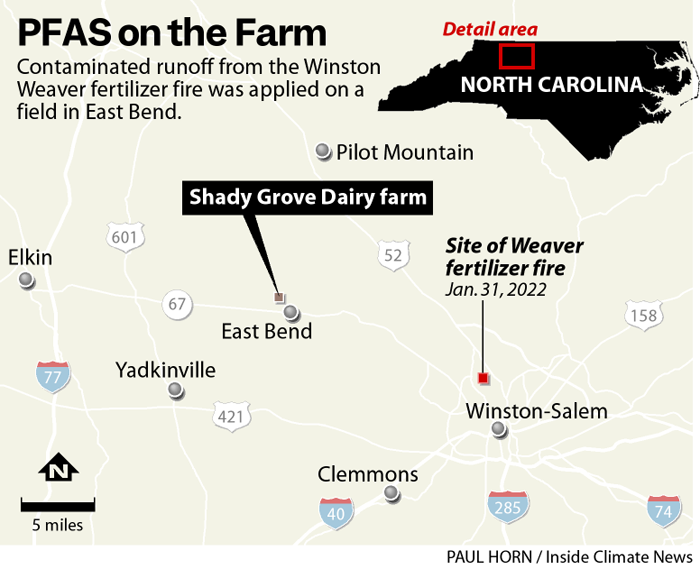

Meanwhile, contractors hired by Winston Weaver built a berm to contain the fire water runoff and prevent it from entering a nearby creek, according to fire officials. And for good reason: The runoff—shipped to a dairy as “off spec liquid fertilizer” and spread on fields—was later found to contain a goulash of dozens of chemicals, including toxic PFAS.

The shipment and application of the off spec fertilizer between Winston Weaver and Shady Grove Dairy has not been previously reported.

Winston Weaver’s off spec fertilizer differed from sewage sludge in that it hadn’t passed through a treatment plant. But even if the material had been treated, PFAS would not have been removed without an advanced and expensive system.

When PFAS-contaminated sewage sludge is applied to farmland, it can contaminate the soil, groundwater, drinking water supplies and food. The connection between sewage sludge and environmental contamination prompted the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to conduct a state-wide sludge survey. The agency plans to publish the results later this year, according to a DEQ.

A week before President Trump was inaugurated for a second term, the EPA published a draft risk assessment of the potential human health risks associated with PFAS in sewage sludge. The agency emphasized that people who live on PFAS-contaminated farms are at higher risk because they eat and drink what they grow.

It’s unclear how the sludge rules will fare under the Trump administration.

Many chemical industry and manufacturing trade associations oppose further restrictions on PFAS. In mid-February, 19 trade groups led by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce sent a letter to EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin with a wish list of PFAS rollbacks, citing what they view as the economic necessity of the compounds and the billions of dollars in cleanup costs.

The letter doesn’t specifically mention sewage sludge but it does call for a review of drinking water standards and the reclassification of PFOS and PFOA from hazardous to non-hazardous substances.

“We stand ready to work with you on these important issues,” the letter reads.

After the fire at Winston Weaver, the Winston-Salem fire Department told DEQ it did not use firefighting foam that contained PFAS to fight the fire at the fertilizer plant. The source of the contamination is still unknown.

Winston Weaver shipped the fire water runoff in steel tanks to Shady Grove Dairy 20 miles away in East Bend. The farm had agreed to take the “off spec liquid fertilizer,” according to an agreement provided to Inside Climate News by state regulators. It was later spread on a field planted with corn silage to feed the cows.

Off spec liquid fertilizer is defined by state regulators as “a product that does not meet quality specifications or standards.”

Shady Grove Dairy owner Tim Smitherman did not respond to emails requesting an interview. Calls for two phone numbers listed in state records for Smitherman did not go through. Former Winston Weaver plant manager Adam Parrish did not respond to emails and a phone message.

When DEQ learned of the agreement between Shady Grove and Winston Weaver, it required sampling of the material to determine whether it would be considered hazardous before allowing it to be shipped, DEQ spokesman Josh Kastrinsky said. Consultants for Winston Weaver analyzed the data and determined it was not hazardous and could be shipped.

After consulting with the EPA, DEQ also required sampling the off spec fertilizer for the compounds.

Without a legal basis to stop the transfer and use of the off spec fertilizer at Shady Grove, the EPA and the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality approved it, state records show.

At the time of the fire, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was still two years from establishing drinking water standards for any PFAS compounds, but had established a drinking water advisory of 70 ppt. Lab samples from the consultant indicated that the highest combined levels in the land-applied water of PFOA and PFOS were below 11 ppt.

That level is now nearly three times the EPA’s drinking water standard.

There are no federal or state rules for PFAS in sewage sludge or the off spec fertilizer bound for farm fields.

More than 66,000 tons of dried sewage sludge was applied on North Carolina’s farm fields for use as fertilizer in 2023, according to state data. As scientists have learned more about how PFAS moves within the environment, they have focused on the compounds’ presence in sewage sludge because of its potential to contaminate the food supply.

“Certain things shouldn’t be applied to the land,” said Jamie DeWitt, a toxicologist who specializes in PFAS research and is a member of DEQ’s Secretaries’ Science Advisory Board. “Regardless of whether or not there were PFAS in the water, it came from a fire at a manufacturing facility. It seems like there would have been other ways to dispose of it.”

In cities, wastewater from homes, businesses and industries discharges to treatment plants, where it becomes sewage sludge that is usually trucked to landfills, incinerated or spread on farm fields. Eighty percent of the 50 largest wastewater treatment plants in the U.S. reported detectable levels of PFAS, according to a 2020 EPA study. The contamination primarily comes from industrial sources that don’t remove the compounds from wastewater before sending it to the plants.

PFAS are also present in some consumer products, and could enter wastewater treatment plants through washing machines, sinks and toilets.

Nationwide, the material has been used on 70 million acres of farmland, sometimes with serious consequences, according to the Environmental Working Group. In Maine, dairy cows that grazed on contaminated fields produced milk with high levels of PFAS, prompting farmers to withdraw their product from the marketplace.

Officials in Johnson County, Texas, declared a state of disaster in February because of PFAS-contaminated agricultural land, soil, groundwater, surface water and animal tissue. In North Carolina, the compounds have been detected in compost.

The EPA’s draft risk assessment for sewage sludge found human health risks exceeded acceptable thresholds when it contained 1 part per billion of PFOA or PFOS, two of the most toxic types.

The off spec fertilizer at Shady Grove contained levels of PFOA and PFOS below the EPA’s threshold of 1 part per billion, published in the draft risk assessment. However it also contained eight to 16 types of the compounds, state records show, depending on which tank was sampled.

The assessment also concludes children who live on dairy farms and drink one to two glasses of milk per day have a significantly higher risk of developing cancer later in life. Their risk of developing non-cancer health effects is also 34 times higher just from that milk than what is considered safe. Adults also face health risks.

People whose drinking water comes from sources on or near farmland polluted with PFAS are also at higher risk of developing cancer or other serious illnesses, according to the draft risk assessment.

State records show that there are several private drinking water wells near Shady Grove Dairy, and there is one on the farm itself. Roughly 1,600 feet from the nearest barn runs a stream that feeds tributaries to the Yadkin River, the drinking water supply for more than 800,000 people.

The EPA still lowballed the threat, according to the Southern Environmental Law Center attorneys Jean Zhuang and Hannah Nelson, who provided public comments on the draft risk assessment.

First, the EPA considered only two PFAS compounds: PFOA and PFOS, “when nearly 15,000 PFAS chemicals plague our environment, surface water, and groundwater,” the attorneys wrote.

Nor did the draft risk assessment account for the combined risk of multiple PFAS or the other sources of the contaminants—clothing, some cookware and consumer products.

“The assessment recklessly underestimates the harm that PFAS-polluted sludge causes to farming families—it must be amended to reflect reality. Sludge is far more polluted than the assessment assumes,” the attorneys wrote.

They also asked the EPA to require industries to pre-treat for PFAS to prevent the compounds from entering the wastewater plants and contaminating the sludge.

“Many of these families unknowingly spread contaminated sludge on their lands because they were told that it was a safe and effective way to fertilize their farms,” the SELC wrote. “Their children and family members are the ones eating the vegetables, beef, fish, fruit, milk, and eggs from their farms. Their families are the ones that have the most to lose.”

The 1,200 cows and calves at Shady Grove Dairy outnumber the people who live in East Bend, in Yadkin County. Over the past decade, state regulators have fined the dairy more than $22,000 for several violations, including allowing cow manure to drain from a waste lagoon into a nearby creek.

The state also cited Shady Grove Dairy in connection with the off spec fertilizer, but not because it contained PFAS. Since the material originated at a fertilizer plant, levels of nitrogen, ammonia and phosphorus were astronomical. DEQ advised farmer Sterling Smitherman against over-applying the fire water runoff, documents show. The agency provided calculations to guide him on the proper application rates, Kastrinsky told Inside Climate News.

Yet when a DEQ inspector visited Shady Grove, unannounced, in March 2022, she found “severe and significant” damage to the silage field from too much nitrogen, state records show. DEQ officials later determined Smitherman “willfully” overapplied the fire water runoff and fined the farm $2,400.

Even though DEQ determined the nitrogen overload “likely” impacted groundwater and surface water immediately after the off spec fertilizer was applied, the agency did not test those areas for PFAS.

“Because the levels present were not in violation of any standards, staff did not conduct follow-up testing on surface water, land or groundwater near the site of application,” Kastrinsky said.

Those compounds could still be on the farm. “Once PFAS get onto the land, they have the potential to stay there for decades, maybe even centuries,” DeWitt said. “They have the potential to move off of that land into air and into water and get transported to other other areas, to broaden contamination and to potentially increase exposures to people living nearby that area of the land application.”

NCDA spokeswoman Andrea Ashby said DEQ did not notify agriculture department officials about the off spec fertilizer; however, Kastrinsky countered that representatives from both agencies discussed the situation.

The state Agriculture Department has not tested any dairy farms for PFAS in milk, Ashby said, because it has not received guidance from the FDA to do so. “The Department’s Food and Drug Protection lab is not set up to test for PFAS or other related chemicals as there is no science-based guidance or established standards at this time to follow for food products.”

PFAS has been detected in gardens in North Carolina. Academic scientists at several state universities tested five residential gardens near the Chemours plant in Fayetteville, a known area of contamination. One type of PFAS compound, GenX, was detected in 72 percent of the 53 samples. Crops containing higher amounts of water had higher amounts of GenX.

The FDA has made progress on testing PFAS in the food supply, according to the agency website. In February, the FDA blocked the import of canned clams from China because of elevated PFAS levels. The agency also has a valid testing method and helps states analyze foods grown, raised, or processed in known areas of contamination before they go to market.

Glenda Pereira is an assistant professor of animal science and a dairy specialist at the University of Maine. She said scientists are studying how PFAS are transferred to crops from soil or irrigation. Unpublished research results from Maine show corn silage tends to have lower levels of PFAS compared with grasses and hay.

“But if the levels in the soil are high enough, the levels in corn silage could be a concern,” Pereira said.

Pereira recommended that farmers who applied PFAS-contaminated sewage sludge on their fields test their soil. The science is still emerging on testing methods, but Maine has published PFOS soil screening levels for several crops as they’re related to dairies and milk production.

Three years after the Winston Weaver fire, the plant has been razed. DEQ reported that subsequent sampling showed the soil contained high levels of arsenic; groundwater had elevated concentrations of several chemicals, including nitrite, nitrate, and benzene—the latter of which is a known carcinogen.

The cause of the fire remains undetermined. State labor department officials fined Winston Weaver $5,600 for violations that could have contributed to the blaze.