News

Cows Can Use Tools. Are We Underestimating How Smart They Are?

Animal Behavior•5 min read

Feature

Research suggests this fishing practice releases up to 370 million metric tons of carbon dioxide every year.

Words by Dawn Attride

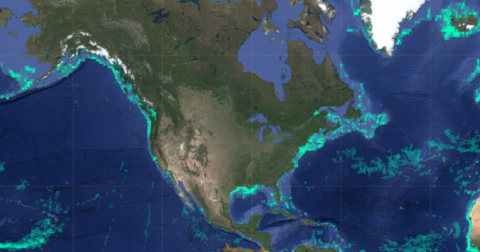

At the depths of the seafloor, life moves and grows eerily slowly. Under crushing pressure and shrouded in darkness, banks of sprawling corals form nurseries for schools of deep-sea fish while the crystalline limbs of 15,000-year-old glass sponges filter bacteria from the water. While most of these habitats are unexplored, some of what we know about species from these ancient ecosystems is dredged up to the surface, caught in the fishing gear of vessels that bottom trawl along the seafloor. A study published earlier this year reveals that while most European countries complied with bottom trawling regulations, other countries ignored them to fish in protected areas. Satellite data uncovered the illegal bottom trawling.

Both illegal and legal forms of bottom trawling are responsible for releasing 370 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

“If nobody is watching and paying attention, the ease at which some of these [regulations] can get swept under the rug or ignored is high,” Russell Moffitt, an author of the study and director of strategic partnerships at the Marine Conservation Institute, tells Sentient. Using publicly available vessel data from Global Fishing Watch, they identified 664 fishing events conducted by 312 bottom-trawling vessels from the end of 2022 to October 2023.

Bottom trawling is a fishing practice of dragging weighted nets across the seabed to catch fish and other marine species, and roughly a quarter of fish eaten globally are caught by this practice.

In both the U.S. and Europe, bottom trawling is banned in certain vulnerable marine ecosystems, which are protected for their rare species and benthic animals — creatures that dwell in the benthic zone or the lowest part of the water.

When nets are dragged along the seafloor, it can eradicate deep-sea species that took millennia to form. That process may not only be bad for sea life, but for climate change as well — specifically the planet’s ability to store carbon and keep it out of the atmosphere. Research shows the ocean floor is an underestimated carbon reservoir, storing approximately 2.3 trillion metric tonnes. If this carbon is disrupted, it can contribute to global warming and ocean acidification, or put simply, excess carbon makes seawater more acidic, which can affect both marine and human health.

As a USGS scientist puts it: “A farmer would never plow his land again and again during a rainstorm, watching all his topsoil be washed away, but that is exactly what we are doing on continental shelves on a global scale.” Regrowing these marine ecosystems and their ancient species after damage could take hundreds of years, if they ever recover, according to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration.

In 2022, the European Commission banned bottom trawling at depths of 400-800 meters in 87 protected areas — upping its restriction from a standing ban on trawling below 800 meters. Some countries supported the ban while others, such as Spain and France, opposed it, arguing it would devastate deep-sea fishers. Knowing this political landscape, an international team of researchers tracked fishing vessel data in European waters to identify how effective the ban was.

Most countries adhered to the regulation, resulting in an 81 percent decrease in bottom-trawling within protected areas, according to their paper published in Science in January. Yet, still some fished illegally in these waters.

Moffitt says their analysis was conservative, as they didn’t want to include bottom-trawling vessels who were just transiting through or fishing on the boundaries of protected zones, and so, the team left out data that could be positional errors in an abundance of caution. “The vessels that we identified…spent a ridiculous amount of time in there. It was not an error…it was obvious what was going on,” he tells Sentient. The team also found the actual restricted areas were much smaller than publicly presented — just 5553 km2, or a little over 2,000 square miles — were closed off to bottom-trawling, a little less than a third of the figure cited by the EU.

Spain bottom-trawled the most in vulnerable marine ecosystems, followed by Portugal and France, according to the findings. This was not a surprise — Spain filed an appeal to annul the 2022 marine protections, arguing that the closures violate the principles of the Common Fisheries Policy, among other things. The appeal has still not been resolved: several environmental NGOs are filing legal actions against countries at fault, as well as a complaint with the European Commission for the bottom trawling activities. Overall, researchers recorded 19,200 hours of illegal trawling over two years.

The reaction to the findings reflects the strong resistance to restrictions on bottom trawling. “Every closure from fisheries is always hotly contested,” Lissette Victorero, first author of the study and science advisor for Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, tells Sentient. “This is 1 percent of EU waters. And still, there’s a court case. There’s complaints. There’s a socioeconomic analysis [by the EU] to try to prove they’re worth closing so you can see how hotly debated every single protection in the ocean is,” says Victorero.

European waters are considered the most trawled globally, with over 50 percent of its surface regularly impacted. For now, the U.S. has more stringent policies –– bottom trawling is prohibited in over half of federal waters, and on the West Coast, 90 percent of the seafloor is closed to bottom trawling.

In contrast, EU consumers have more clarity on where their fish comes from. Labels on unprocessed fish must state the type of fishing gear used — including trawling equipment — but there is no such requirement in the U.S.

There is a distinction between regular bottom trawling and doing so in areas identified as vulnerable ecosystems, where species that are vulnerable can take a long time to recover. “Vulnerable marine ecosystems are rare and they’re not your typical bottom trawling habitats,” Ray Hilborn, a professor at the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences at University of Washington tells Sentient. Hilborn, who was not involved in the study, has published research on best industry practices to minimize environmental impacts caused by bottom trawling, but has also been criticized by some environmental advocates for being an “overfishing denier.”

Aside from effects on marine species, bottom trawling contributes to global warming, research suggests, although there is still debate over how much. A paper published last year in Frontiers in Marine Science estimated the amount of carbon released by bottom trawling to be up to 370 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. For context, that’s the same amount of carbon dioxide needed to heat nearly 50 million homes in one year, according to the EPA’s greenhouse gas calculator.

Using satellite data and carbon cycle models, the researchers posit that 55-60 percent of trawling-induced carbon dioxide is released to the atmosphere over 7-9 years, leading to ocean acidification. “Bottom trawling disrupts the sediments that have stored carbon for centuries in the ocean, [releasing] carbon back into the water and ultimately into the atmosphere while it should really be sequestered away for thousands of years in the deep sea,” Victorero explains.

Deep-sea fish can also play a vital role in carbon sequestration. They eat carbon-rich organisms throughout their life and when they die, their bodies sink, transferring that carbon to the ocean floor. Along the UK and Irish continental slope, this process was estimated to store more than 1 million tons of carbon dioxide every year.

Despite increased regulations, bottom trawling continues to be a dominant method of fishing, with clear environmental impacts, particularly in vulnerable ecosystems. If Spain were to win their case against the EU, it would set a concerning precedent for further protections in these areas. “One trawl is one too many to destroy species that may be irreplaceable at least in our lifetimes,” Moffitt says.