Investigation

‘You Feel Like You’re Marked’: Salvadoran Workers at Tyson Foods Face Risks Due to Work Permit Delays

Policy•9 min read

Explainer

What you need to know about how these laws seek to censure whistleblowers.

Words by Seth Millstein

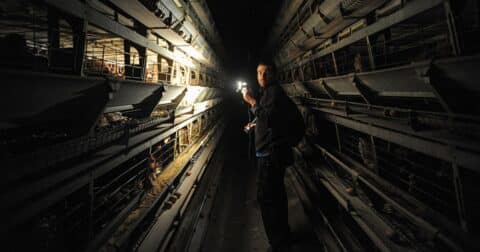

In 1904, journalist Upton Sinclair went undercover in Chicago’s meatpacking plants and documented the health and labor violations he saw. His findings shocked the world, and led to the passage of the Federal Meat Inspection act two years later. But this kind of undercover journalism is now under attack, as “ag-gag” laws around the country attempt to prohibit journalists and activists from doing this kind of important, lifesaving work.

Here’s what you need to know about what ag-gag laws do — and the fight to strike them down.

Ag-gag laws make it illegal to film the inside of factory farms and slaughterhouses without the owner’s permission. While they come in many varieties, the laws typically prohibit a) the use of deception to gain access to an agricultural facility, and/or b) the filming or photographing of such facilities without the owner’s consent. Some ag-gag laws specify that it’s illegal to film these facilities with the intent to do “economic harm” to the company in question.

Many ag-gag laws also require people who witness animal cruelty to report what they’ve seen within a relatively short period of time. While this may seem like a good thing, requirements like this make it effectively impossible for activists to conduct long-term investigations into animal cruelty at farms.

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, animal rights activists successfully infiltrated factory farms and documented activity in them that violated anti-cruelty laws. These investigations resulted in raids, prosecutions and other high-profile legal actions against the violators. Ag-gag laws were proposed by the agricultural industry in the 1990s in an attempt to prevent activists from carrying out these sorts of exposés.

The first anti-gag laws were passed in Kansas, Montana and North Dakota between 1990 and 1991. All three of them criminalized the unauthorized entry and recording of animal facilities, while the North Dakota law also made it illegal to set animals free from such facilities.

In 1992, Congress passed the federal Animal Enterprise Protection Act. This law enacted additional penalties for people who intentionally disrupt animal facilities by damaging them, stealing records for them or releasing animals from them. This was not an ag-gag law itself, but by singling out animal rights activists for special punishment at the federal level, the AEPA contributed to the demonization of such activists, and helped pave the way for the next round of ag-gag laws that passed in the 2000s and beyond.

Ag-gag laws have been criticized for several different reasons, with critics arguing that they violate the First Amendment and whistleblower protections, imperil food safety, reduce transparency of the agriculture industry and allow animal cruelty and labor laws to be violated without consequence.

The central legal objection to ag-gag laws is that they restrict freedom of speech. That’s the conclusion many judges have come to; when ag-gag laws are struck down in the courts, it’s usually on First Amendment grounds.

The Kansas ag-gag law, for instance, made it illegal to lie to gain access to an animal facility if the intent is to do harm to the business. The Tenth Circuit determined that this violated the First Amendment, as it criminalized speech based on the intention of the speaker. The majority on the court added that the provision also “punishes entry [to an animal facility] with the intent to tell the truth on a matter of public concern,” and struck down most of the law.

In 2018, the Ninth Circuit upheld a similar provision in Idaho’s ag-gag law. However, the court struck down a portion of the law that banned unauthorized recording inside animal facilities, ruling that it violated “journalists’ constitutional right to investigate and publish exposés on the agricultural industry,” and noting that “matters related to food safety and animal cruelty are of significant public importance.”

The federal Safe Meat and Poultry Act of 2013 contains whistleblower protections for meat and poultry production workers. But some ag-gag laws directly conflict with these federal protections; if workers at an animal facility were to collect and share information about lax food safety protocols without their employers’ permission, they could be in violation of state ag-gag laws, even though such behavior is protected under the 2013 federal law.

Animals are treated terribly in factory farms, and one of the ways we know this is because activists and journalists have conducted undercover investigations of such farms. Over the decades, their findings have informed the public about how their food is produced, prompted legal action against criminals in the animal agriculture industry, and led to increased legal protections for animals.

An early example of this took place in 1981, when People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) co-founder Alex Pacheco took a job at a federally-funded animal research laboratory in Maryland and documented the horrific conditions in which the facility’s monkeys were kept. As a result of Pacheco’s investigation, the lab was raided, an animal researcher was convicted of animal cruelty and the lab lost its funding. PETA’s undercover investigation contributed to the passage of major amendments to the Animal Welfare Act in 1985.

Ag-gag laws are an attempt by the agriculture industry to prevent these kinds of investigations from taking place. As such, the laws reduce transparency of the agriculture industry by limiting public awareness about what goes on in such facilities, and make it more difficult to take legal action against those who violate anti-cruelty laws.

In September, the US Labor Department began investigating Perdue Farms and Tyson Foods after a New York Times report revealed that they were employing migrant children as young as 13. One 14-year-old boy’s arm was nearly torn off at a Perdue slaughterhouse after his shirt got caught in a machine.

Labor abuse is extremely common in the agriculture industry. A 2020 report by the Economic Policy Institute found that over the preceding two decades, more than 70 percent of federal investigations into agriculture businesses uncovered violations of employment law. Ag-gag laws exacerbate these problems by creating an additional liability for agricultural workers who might seek to document their mistreatment at work.

It’s relevant to note here that in the U.S., the agriculture industry has a higher share of undocumented employees than any other sector. Undocumented immigrants are often reluctant to tell authorities when they’re being victimized in one way or another, as doing so can potentially risk exposing their citizenship status. As such, this makes them easy targets for employers who want to save a couple of bucks by, say, skimping on safety protocols. Needless to say, undocumented employees are probably going to be even less likely to report mistreatment in states with ag-gag laws.

Since the initial flurry of ag-gag laws in the early ‘90s, similar legislation has been proposed in statehouses across the country — often after high-profile investigations revealed wrongdoing at agriculture facilities. Although many of these laws either didn’t pass or were later struck down as unconstitutional, some survived, and are currently the law of the land.

Alabama’s ag-gag law is called the The Farm Animal, Crop, and Research Facilities Protection Act. Passed in 2002, the law makes it illegal to enter agricultural facilities under false pretenses, and also criminalizes the possession of those facilities’ records if they were obtained through deception.

In 2017, Arkansas passed an ag-gag law that directly targets whistleblowers — in all industries, not just agriculture. It’s a civil statute, not a criminal one, so it doesn’t directly ban undercover recordings in farms and slaughterhouses. Rather, it states that anybody who makes such a recording, or engages in other clandestine activities on business properties, is responsible for any damages that the owner of the facility incurs, and empowers the owner to seek such damages in court.

Amazingly, this law applies to all business properties in the state, not just agricultural ones, and covers records theft as well as unauthorized recordings. As a result, any potential whistleblowers in the state are liable to be sued if they rely on documents or recordings to blow the whistle. The law was challenged in court, but the challenge was ultimately dismissed.

In 1991, Montana became one of the first states to pass an ag-gag law. The Farm Animal and Research Facility Protection Act makes it a crime to enter an agriculture facility if entry is forbidden, or to take pictures by photograph or video recording of such facilities “with the intent to commit criminal defamation.”

In 2008, PETA released a video that showed workers at an Iowa pig farm savagely beating animals, violating them with metal rods and at one point instructing other employees to “hurt ‘em!” Six of these workers subsequently pleaded guilty to criminal livestock neglect; up to that point, only seven people had ever been convicted of animal cruelty for actions they took while working in the meat industry.

Since then, Iowa lawmakers have passed no fewer than four ag-gag bills, all of which have been subject to legal challenges.

The first law, passed in 2012, made it illegal to lie in order to get hired at a job if the intent is to “commit an act not authorized by the owner.” That law was ultimately struck down as unconstitutional, prompting lawmakers to pass a revised version with a narrower scope several years later. A third law increased penalties for trespassing on agriculture facilities, while a fourth made it illegal to place or use a video camera while trespassing.

The legal history of these bills is long, winding and ongoing; as of this writing, however, all of Iowa’s ag-gag laws other than the first one are still in effect.

Missouri’s legislature passed an ag-gag law as part of a larger farm bill in 2012. It states that any evidence of animal abuse or neglect must be turned over to authorities within 24 hours of obtaining it. This requirement makes it impossible for activists or journalists to collect more than a day’s worth of evidence of wrongdoing in animal facilities without going to authorities, and potentially blowing their cover.

In February of this year, the Kentucky legislature passed an ag-gag bill making it illegal to take photographs inside factory farms — or via drones, above factory farms — without the owner’s permission. Although Gov. Andy Beshear vetoed the bill, the legislature then overrode his veto, and the bill is now law.

Another early adopter of ag-gag laws, North Dakota passed a law in 1991 that made it a crime to damage or destroy an animal facility, release an animal from it or take unauthorized pictures or video from inside it.

Idaho passed its ag-gag law in 2014, shortly after an undercover investigation showed farm workers abusing dairy cattle. It was challenged in court, and while the portions of the law that banned covert recording of agriculture facilities were struck down, the courts upheld a provision that bans people from lying in job interviews in order to gain access to such facilities.

The outlook isn’t quite as bleak as the above eight states might suggest. In five states, ag-gag laws have been struck down by the courts, in whole or in part, as unconstitutional; this list includes Kansas, which was one of the first states to pass such a law. In 17 other states, ag-gag bills were proposed by state legislators, but never passed.

This suggests that there are at least two useful tools for fighting against ag-gag: lawsuits and elected officials. Electing politicians who oppose ag-gag laws, and supporting the organizations that sue to have them overturned, are two of the best ways individuals can help ensure transparency in farms, slaughterhouses and other animal facilities.

A couple of the organizations that fund lawsuits against ag-gag laws are:

Despite some encouraging developments, the fight against ag-gag is far from over: Kansas lawmakers are already attempting to rewrite the state’s ag-gag laws in a way that passes constitutional muster, and an ag-gag law in Canada is currently making its way through the courts.

Make no mistake: ag-gag laws are a direct attempt by the agriculture industry to avoid transparency and accountability. Although only eight states currently have ag-gag laws on the books, similar legislation passing elsewhere is a perpetual looming threat — to food safety, to worker’s rights and to the wellbeing of animals.