News

GLP-1 Users Lose Weight, and Their Taste for Meat

Research•3 min read

Reported

The human emotional toll of experimenting on animals.

Words by Valerie Monckton

Kim’s promotion paved the way for one of the worst days of her life. For about two dollars more per hour, she was now required to euthanize eight beagles she’d spent months caring for. Their deaths were the final stage in a routine experiment testing a drug’s effects at increasing doses.

“The most traumatizing part of that was that I’d have to be like an angel of death and give them the needle. Bring them under a tarp on a table, tie all four limbs,” she tells Sentient. When she brought the newly euthanized dog into the next room, she’d see the last lifeless dog she’d brought in, butterflied open on the table.

“People were actually laughing at me because, ‘Oh, you’re crying.’”

Researchers, veterinarians and animal care staff working with laboratory animals have long struggled with emotional stress. Their work demands that they attend to the wellbeing of animals whose suffering and deaths they are often powerless to prevent — and themselves frequently cause — placing them in a uniquely stressful situation called the “caring-killing paradox.”

A 2021 study reported that 72 percent of surveyed participants who conducted experiments on animals considered animal experiments an emotional burden. How laboratory workers relate to these animals to cope with this burden varies: some form close attachments to them, others objectify them and still others view them like “dying nursing-home patients.” That same 2021 survey also found that 47 percent of participants feel that many animal experiments are unnecessary.

They’re not wrong. Species differences, poor experimental design and animal welfare violations — even in laboratories accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care — represent a few of the many serious barriers facing the applicability of animal research in humans. As alternatives to animal use in testing and research are developed, more people are questioning whether experimenting on millions of animals a year — for flawed results — is worth the cost.

Concern for the wellbeing of those who experiment on animals has existed for centuries. According to the book Animal Welfare and Anti-Vivisection 1870-1910, Victorian anti-vivisectionists argued that people conducting or watching vivisection would be “coarsened” by it, and commit violent acts against disabled people, women and children. Today, our emotional struggle with animal experimentation continues: a recent thread on X (formerly Twitter) that discussed biology students’ distress at causing the suffering and death of their animal subjects reached over 2.6 million views.

Yet, to date, little scientific research investigates the effect of this work on workers’ mental health. A 2023 systematic review found only 12 studies that focused on laboratory animal professionals and investigated psychological strain due to workplace stressors. Only one of those included a control group that didn’t experiment on animals. Still, research shows that working with laboratory animals is a source of both acute and chronic stress, particularly if the job involves euthanizing animals. It also shows that social support — talking about the emotional burden of the work with colleagues, family and friends — is one of the few reliable ways to ease that stress.

That crucial support is scarce. Madeline Krasno, a former student animal caretaker at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Harlow Primate Laboratory (named for the infamous Harry Harlow), said that she kept to herself, afraid that speaking up would cost her the job. “It’s just better not to talk to each other, because what if they don’t agree and we get labeled an activist?” Krasno tells Sentient. When Krasno left and began to connect with other former lab workers, she found that many felt the same way.

A spokesperson from the University of Wisconsin-Madison provided Sentient with a response (published here), stating in part “Students and employees at UW-Madison have a range of venues in which to share concerns about their own health and well-being and access related care and services.”

Kim’s experience wasn’t much different from Krasno’s account. She alleges that Charles River, an American pharmaceutical company specializing in pre-clinical and clinical drug trials, gave her a copy-and-paste explanation about her work at the lab to share with friends and family. Yet she couldn’t turn to colleagues, either. Kim alleges that the person responsible for training her would mock her with fake crying every time they passed one another. She says another coworker quipped that their workplace afforded many ways to kill themselves — and still get life insurance money for their families.

Charles River did not respond to Sentient’s multiple requests for comment.

At best, Kim says her colleagues encouraged her to build an emotional shell to shield her from the trauma she’d experience. She suspects they were too numb to provide anything more. That numbness could be a side effect of watching animals suffer — and inflicting their suffering. Slaughterhouse workers also report feeling dissociated and numb as a result of the violence they witness.

It may also be a side-effect of a common coping mechanism: creating emotional distance with those in your care. In 2020, a study asked veterinarians and vet techs working with laboratory animals if they thought it best not to become too emotionally involved with the animals in their care. Their opinions were polarized: 74 percent of responses were divided between the “strongly disagree–disagree” range and the “agree–strongly agree” range.

Aside from getting emotional support from other humans, attachments with animal subjects can also help workers cope. Of course, this assumes that they’re allowed adequate time to build those bonds. Krasno says that, on the weekends, only two students were responsible for the care of over 500 monkeys at the Harlow Primate Laboratory. A spokesperson for the university disputed Krasno’s account, calling it “inaccurate,” and adding in part that “The care and oversight of the animals was overseen by highly experienced staff that part-time caretakers like Krasno reported to each day and who were available in the event there were any issues — animal-health related or otherwise — in the facility.

Meanwhile, animals used in pre-clinical drug trials at Charles River have a time limit imposed on every task required for their care, which includes mandatory socialization time. “There’s 20 dogs, so each dog gets a minute of, ‘Hello, I love you,’ and then you go to the next dog,” Kim says. Kim also alleges that most of her colleagues couldn’t even tell the dogs apart without their IDs.

Little time for the animals also means that the smallest setback in personnel reduces animal welfare. According to Kim, if management had allowed a colleague to help her euthanize the beagles, the dogs wouldn’t have needed to be strapped to a table and could have had a far more humane death.

Poor animal welfare can also compromise the studies themselves: in some cases, animals stressed by poor handling and environmental conditions have been found to “have profound differences in their biology compared to non-stressed animals.”

This relationship works both ways. Research shows that when laboratory staff build bonds with the animals in their care, animal welfare improves. Many aspects of a study, like lighting and disturbances, can be challenging to alter to improve animal welfare; encouraging human-animal bonds in the lab may be one of the easiest ways to enhance welfare and ensure more accurate animal models.

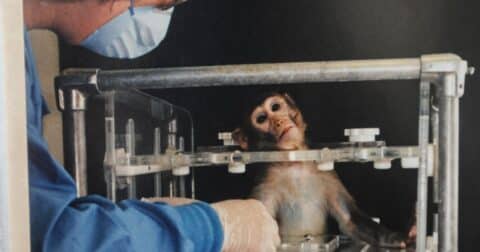

In 2012, a PhD thesis published by the University of Stirling studied the welfare and biological data of two groups of rhesus macaques: a group who received increased socialization with animal care staff and another who didn’t. The study found that socialization led to less varied data and more sensitive and reliable cardiovascular readings. Socialization also improved the care staff’s morale and significantly improved the macaques’ welfare.

Whether treating animals better results in more reliable findings has not been widely researched; however, the University of Stirling’s research suggests that people caring for animals in the laboratory may directly affect research outcomes depending on how they treat animals. Given the reproducibility crisis in biomedicine — that is, the problem that many scientific studies can’t be reproduced to yield the same results — you might expect more research facilities to take extra care to protect this bond. Yet, having a strong bond with a laboratory animal can also contribute to poorer mental health outcomes for workers, who may grieve for the suffering and death of the animals they are bonded to.

“For Patrick” is tattooed on Krasno’s left bicep in honor of the baby macaque she named in her first month working for the Harlow Laboratory, a primate breeding and psychology research facility. “I am holding this tiny baby monkey. I’m syringe feeding him. He’s got his hands wrapped around my hand and his legs wrapped around my wrist. It’s the sweetest thing. And what is his life gonna be? I care so deeply for these animals, and I’m preparing them to have God knows what will happen to them.”

It wasn’t an unrealistic fear. Norm, a monkey both named and beloved by Krasno’s colleagues, was one of very few macaques at the Harlow Laboratory who sought human companionship. Norm would press his arm against the cage bars to be groomed by care staff, and groom the staff in return. “You always wanted to say hi to him. There’s something so heartwarming and, at the same time, so sad about it,” Krasno recalls. One day, Norm was gone. He’d been put in an alcohol study.

“He had unlimited access to alcohol. And I don’t know what happened to him after that, but I can imagine that it wasn’t good. They’re in such an unnatural and depressing situation and then to give them a substance like that? I imagine he probably drank himself to death.”

Krasno went out of her comfort zone to ask about Norm’s fate. Yet, both she and Kim rarely knew the details of experiments that manipulated the lives of the animals they cared for. Some research suggests that communicating with care staff about research outcomes may improve their mental health. Krasno and Kim were unconvinced. “It just was a reminder that they all think it’s important, but I didn’t really make much sense of it,” Krasno says of research successes posted on billboards in the Harlow Laboratory. Kim said that she loved hearing about the importance of animals in medical advancements — but that was before she had to hold an animal while a colleague force-fed the animal drugs.

Their experiences in the lab have left a mark. Krasno’s experience led her to be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in 2019, while Kim’s experience exacerbated her existing complex PTSD.

Research released this April proposed best practices for animal facilities, and acknowledged that there was no way to escape the ethical dilemma of both caring for and harming animals. It stressed that animal facilities must constantly and critically examine their practices, and do everything in their power to meet the welfare needs of both animals and personnel. To do so, it endorsed changing the 3Rs of animal research (replacement, reduction, and refinement) to the 6Rs — adding respect, responsibility and reproducibility — to support staff wellbeing.

For Kim, the most important R is clear: replacement.

In the meantime, researchers like Dr. Charu Chandrasekera, the founder of the Canadian Centre for Alternatives to Animal Methods at the University of Windsor, is working on alternatives that would allow the field to “reduce as much as possible.” During a 2022 interview with the CBC, she described a number of promising alternatives, some of which are already in use, including testing on disembodied human hearts made to beat again, “human cells and tissues from cadavers,” and engineered organoids on chips. Researchers are even designing alternatives to toxicity testing on dogs. While the alternatives are far from the norm, there are efforts to move them forward happening around the world. Chandrasekera told the CBC, “I’m very hopeful.”