News

Grasslands and Wetlands Are Being Gobbled Up By Agriculture, Mostly Livestock

Research•4 min read

Solutions

Combining eating more plants with collective action — like getting hospitals and schools to serve more plant-based dishes — can make your individual climate action far more effective.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

When it comes to tackling climate change and industrial animal agriculture, a long-standing debate continues to divide advocates — is it better to focus on individual dietary shifts, or demand systemic change? Over the last decade or so, environmental and animal welfare organizations have grappled with how to combine individual behavior change with a broader push for collective action. Is it more effective to urge consumers to eat less meat, or to target meat and dairy companies to transition toward plant-based alternatives? Are individual shopping choices more impactful, or should we prioritize boycotts and pressure campaigns through grassroots activism?

A new report from the World Resource Institute reveals that both strategies can — and in fact must — work together. To combat climate change, the report finds, collective change and individual action require a joint effort.

“This research shows that people really can’t do it alone,” Mindy Hernandez, one of the authors of the WRI report, tells Sentient. “They need help in order to realize the very significant emissions reductions that are possible.” Rather than getting caught up in the idea that “‘corporations need to do something, or nothing matters,’ systems-level players, specifically policy and industry actors, have a massive role to play.” At the same time, Hernandez adds, “that does not give individuals a free pass.”

The idea of a “personal carbon footprint” didn’t come from climate scientists or environmental advocates — it actually came from Big Oil, as a means of placing the onus on us. In 2004, British Petroleum (BP) introduced the carbon calculator, reframing the climate crisis as a matter of personal responsibility. The message was simple: Don’t look at us. Look at yourself.

We’re still grappling with the legacy of that messaging. A little more than 20 years later, global emissions continue to rise yet conversations around food and climate tend to be framed in terms of individual choices — both the effective ones like eating less meat and the not-so-effective ones for climate emissions, like buying local, “climate-friendly,” “regenerative” or organic.

Meanwhile, the beef industry continues to pump out emissions, with little political will to tackle these emissions in a meaningful way.

Around a third of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food, and most of those food-related emissions are driven by meat, especially beef. Americans and other Global North countries must eat less meat and shift to more plant-forward diets, the research suggests. “Plant-based foods — such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, beans, peas, nuts, and lentils — generally use less energy, land, and water, and have lower greenhouse gas intensities than animal-based foods,” according to the United Nations.

WRI’s research also finds that “pro-climate behavior changes” are enough, potentially, to “theoretically cancel out all the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions an average person produces each year — specifically among high-income, high-emitting populations.” One of those climate-crucial behaviors, the research reveals, is cutting back on meat and dairy — especially beef and lamb.

Organic or regenerative food have various merits, but these do not include a reduction in climate emissions for beef, because organic and regenerative cattle ranching requires more land, and land has a climate emissions cost. Ultimately, none of these personal actions come close to the environmental impact of shifting away from meat and other animal-sourced products. “Full veganism can save nearly 1 ton of CO2 annually, about a sixth of the average global citizen’s total emissions. But even reducing meat intake captures 40% of that impact,” the report states.

The WRI research also makes a larger point: focusing solely on individual behavior is not sufficient on its own. Without systemic change, we unlock just a fraction — about 10 percent — of our true climate action potential.

The other 90 percent, according to WRI, “stays locked away, dependent on governments, businesses and our own collective action to make sustainable choices more accessible for everyone. (Case in point: It’s much easier to go carless if your city has good public transit.)”

Consider a student working to decrease their individual climate impact by eating less meat, WRI’s Hernandez suggests. A systemic action the student could take would be to advocate for the school to adopt Meat Free Mondays or WRI’s Cool Food Pledge, a program that helps organizations reduce the climate impact of their food offerings by shifting to plant-rich menus.

“Suddenly it’s really easy for that student to keep their commitment to eating less meat,” says Hernandez, and the collective emissions of the larger student body also then decreases.

The key is to have climate action, at both individual and systemic levels, working in unison. “Systemic pressure creates enabling conditions, but individuals need to complete the loop with our daily choices. It’s a two-way street,” the WRI researchers write. “Bike lanes need cyclists, plant-based options need people to consume them.” And when more of us adopt these behaviors, “we send critical market signals that businesses and governments respond to with more investment.”

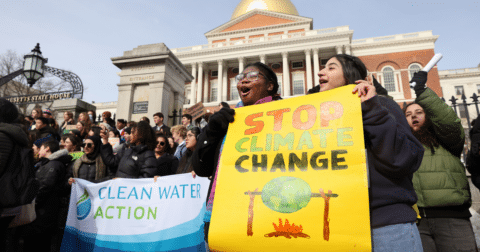

As the current administration continues to roll back environmental protections, it’s a crucial time for both individual and collective action, Lauren Ornelas, founder of the nonprofit Food Empowerment Project, tells Sentient. “We can’t say ‘I can rely on the government to pass regulations that are good for the environment or that are good for the welfare of animals,’ or ‘I can rely on my policymakers to do those things.’ It’s kind of up to us,” she says, “and this is the best time to acknowledge that in every aspect [where] we actually have power.”

For those who care about food system impacts, that power can be found in what we choose to eat. “Food choices are always empowering,” says Ornelas. So is taking part in a broader collective action, she adds, “to make sure that we are joining our voices with others to demand change.”

And what could this look like? “Focus on the one thing that you think you can do in your household,” Hernandez says.” And then, think about what is the one systems-level thing you can do,” like joining a local environmental or food justice group. Shifting diets away from meat and dairy may not solve the climate crisis alone, but eating less meat can be one empowering individual choice that can be made that much stronger by collective action.