Feature

Budget-Friendly Foods Can Be Better, for Both You and the Planet

Climate•5 min read

Feature

Going from 100 lbs of chicken each year to 63 would be quite the change.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

The advice to eat less beef and more chicken has become a common refrain — at least in certain climate circles. Proponents point to beef’s outsized emissions and chicken’s comparatively smaller carbon footprint, arguing chicken is much better for the planet. Some regenerative chicken farms are capitalizing on that advice: one New York City restaurant, Coqodaq, is charging $42 per person for a bucket of regenerative chicken (and sides). Regenerative farmers say the way they farm is better, for both the environment and the birds, but research suggests there are tradeoffs. A switch from factory farmed chicken to chicken from higher welfare and more environmentally friendly systems can only be feasible, modeling suggests, if we reduce the amount of chicken we eat to a little over half of what we eat now.

In the 2021 study, researchers looked at organic and free-range farms, which offered birds more space to roam and raised slower-growing breeds as compared to factory farm chickens. While the study did not look at regenerative chicken specifically — a term that does not have a standardized or legal definition — the research offers insights into the environmental tradeoffs of switching to organic and free-range.

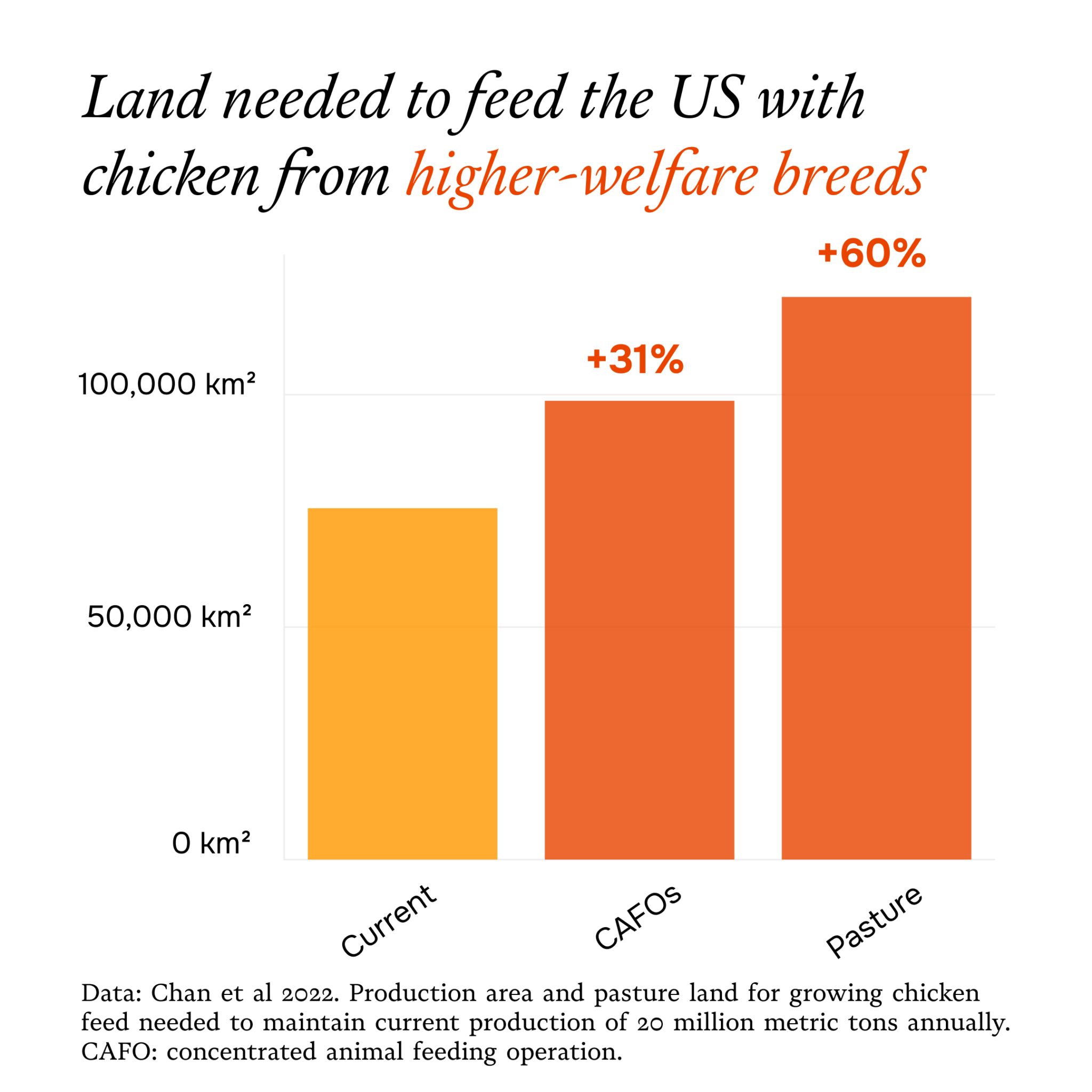

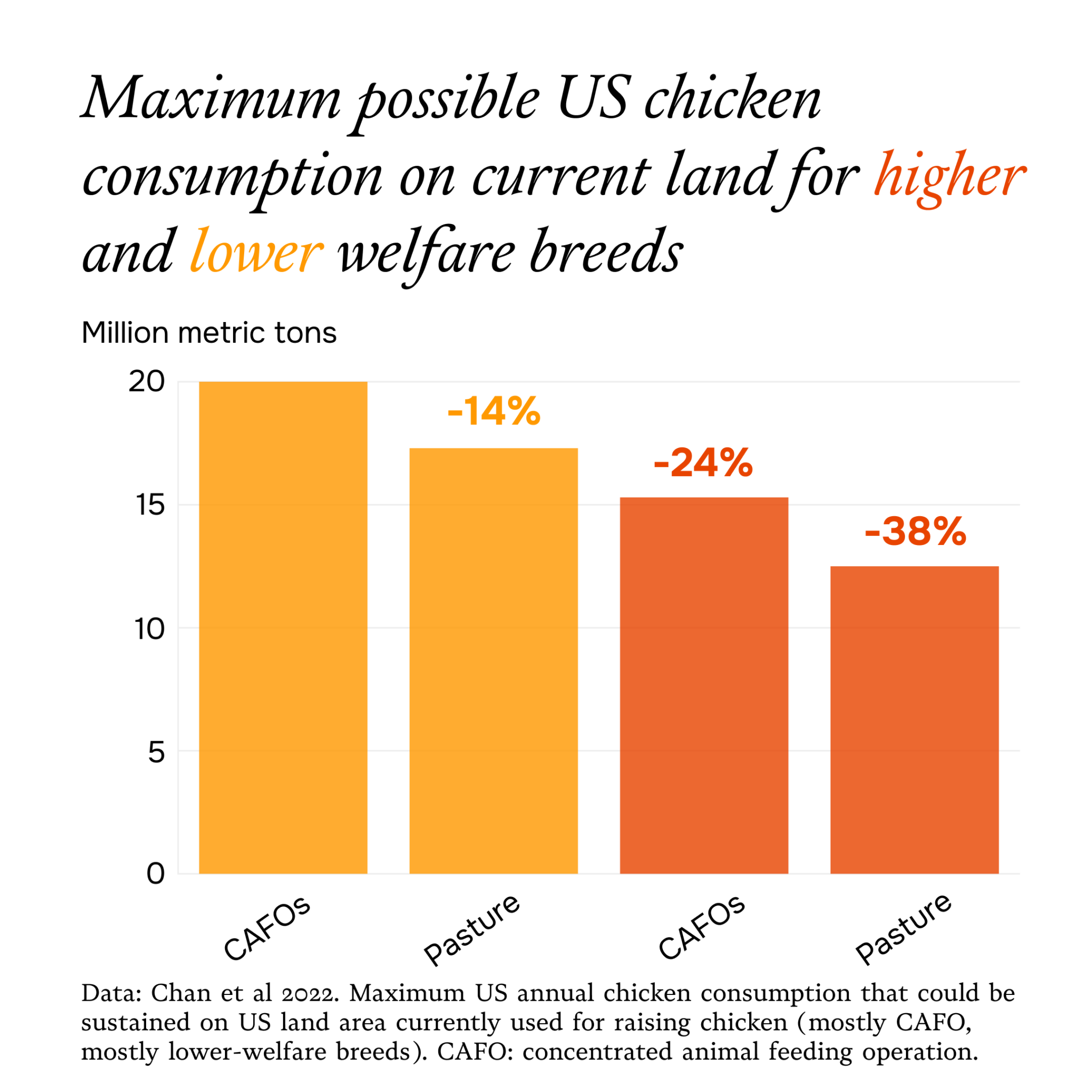

To be precise, the study found that a national switch to higher welfare chicken (slow growing, on pasture) would require up to 60 percent more land. The researchers describe this potential switch as “untenable” — it would only work if per capita chicken consumption decreased by 37 percent.

In 2023, per capita chicken consumption in the U.S. was 100 lbs by 2023. Dropping that by 37 percent would equate to around 63 lbs of chicken per year, or about as much chicken that was being consumed in the early nineties. In other words, this would mean a huge change in the way Americans eat.

The welfare pitch for slower-growing breeds, such as the Rowan Ranger, is that these birds suffer fewer injuries and illnesses, and live longer, at least by a couple of weeks, before reaching slaughter weight. On most factory farms, the common breed of chicken used is the fast-growing Ross 308, which reaches slaughter weight in just 47 days. As a result of their rapid growth, these birds can suffer muscle strains, heart disease and bone breaks.

There are environmental tradeoffs however, that come with slower growing breeds and more space. In order to have more land, for the chickens to roam and to grow food for them, farmers will have to expand, which comes with deforestation, the process of destroying uncultivated habitats to create something else, in this case, farms. More deforestation means fewer wild habitats and shrinking biodiversity, the authors point out.

Regenerative farming can have some benefits for soil health, studies show. But in terms of local environmental impact — looking at the impact to surrounding wildlife and waterways — there isn’t enough data to know for sure.

Matthew Hayek, an environmental scientist at New York University who co-authored the 2021 study, told Sentient by email that “regenerative chicken farming may enhance local biodiversity, or at least it may be less bad for it than an intensive industrial chicken operation. However, we lack data evaluating this at the farm level.”

One issue is that applying chicken manure properly is no simple feat. Hayek also told Sentient over email, So while nitrogen found in animal waste is a useful fertilizer, he writes, it’s also easy to over-apply. Apply too much and “it seeps into groundwater and runs off into nearby streams. Even small-scale farms can cause this if nitrogen is not being carefully managed.”

“It’s not clear whether the land they are on requires or can even handle these ongoing, long-term additions of nutrients. Adding nutrients to land is a bit like wetting a sponge: add too much and it leaks all over.”

Green Circle’s regenerative chickens, the breed sold at Coqodaq in New York, are raised in a “pasture-based system of farming, where the waste is composted and returned to the soil to build the health of the land,” according to the website for D’Artagnan, a distributor for the product.

While composting manure might help stabilize nutrients and lower the risk of water contamination compared to raw manure application, it still requires careful management to prevent leaching and nutrient loss.

Higher welfare chicken farming systems also emit more greenhouse gases. A 2022 report by the World Wildlife Fund found that factory chicken farms produce the lowest greenhouse gas emissions when compared to other kinds of chicken farms, like organic. Slower-growing breeds and less efficient feed conversion — more grain is needed per pound of meat — results in more climate pollution. According to the researchers, because organic flocks are slaughtered at heavier weights, they require longer lifespans — more feed, land and manure.

Hayek and his co-authors describe a scenario in the study where a switch to regenerative chicken might be possible — that is, if everyone ate far less chicken. But cutting back on chicken consumption or production isn’t usually part of conversations around regenerative farming. In the Regenerative Farmers of America’s Core Principles of Regenerative Chicken Farming for instance, there is no mention of reducing production or consumption.

For a recent series on regenerative agriculture presented by TableDebates.org, the authors offer one possible explanation. Some proponents of regenerative agriculture, they write, “hesitate to endorse lowering meat consumption,” worrying that the higher emissions impact will stigmatize regenerative meat, “which they argue are part of the solution.”

Advocates for any kind of food system change will tend towards highlighting the benefits of their proposed solution over the challenges. A farm might be better for animals and worse for climate change. A change to how we eat could solve a lot of problems at once but also be really unpopular. Food is complicated and it’s personal, but ultimately every proposed food system solution comes with tradeoffs, and getting people to talk about those tradeoffs is better than not talking about our food system at all.