Feature

Southern Right Whales Are Having Fewer Calves. Scientists Say a Warming Ocean Is to Blame.

Climate•6 min read

Analysis

A trio of new reports — including the IPCC's latest — makes clear that food system reform is a crucial part of climate action.

Words by Caroline Christen

The IPCC has now released its latest report with an urgent warning to the world — the leading climate agency called “the pace and scale of what has been done so far insufficient to tackle climate change.” The agency has now published the full report here.

Unless lawmakers act now, human activities will continue to drive up greenhouse gas emissions, putting 30,652 species at risk. Yes, reducing fossil fuel emissions is critical, the report states, but the IPCC’s research also makes clear that the current global food system is unsustainable. If we don’t change our food system — including adopting more sustainable plant-rich diets — food insecurity in the most vulnerable communities will undoubtedly increase.

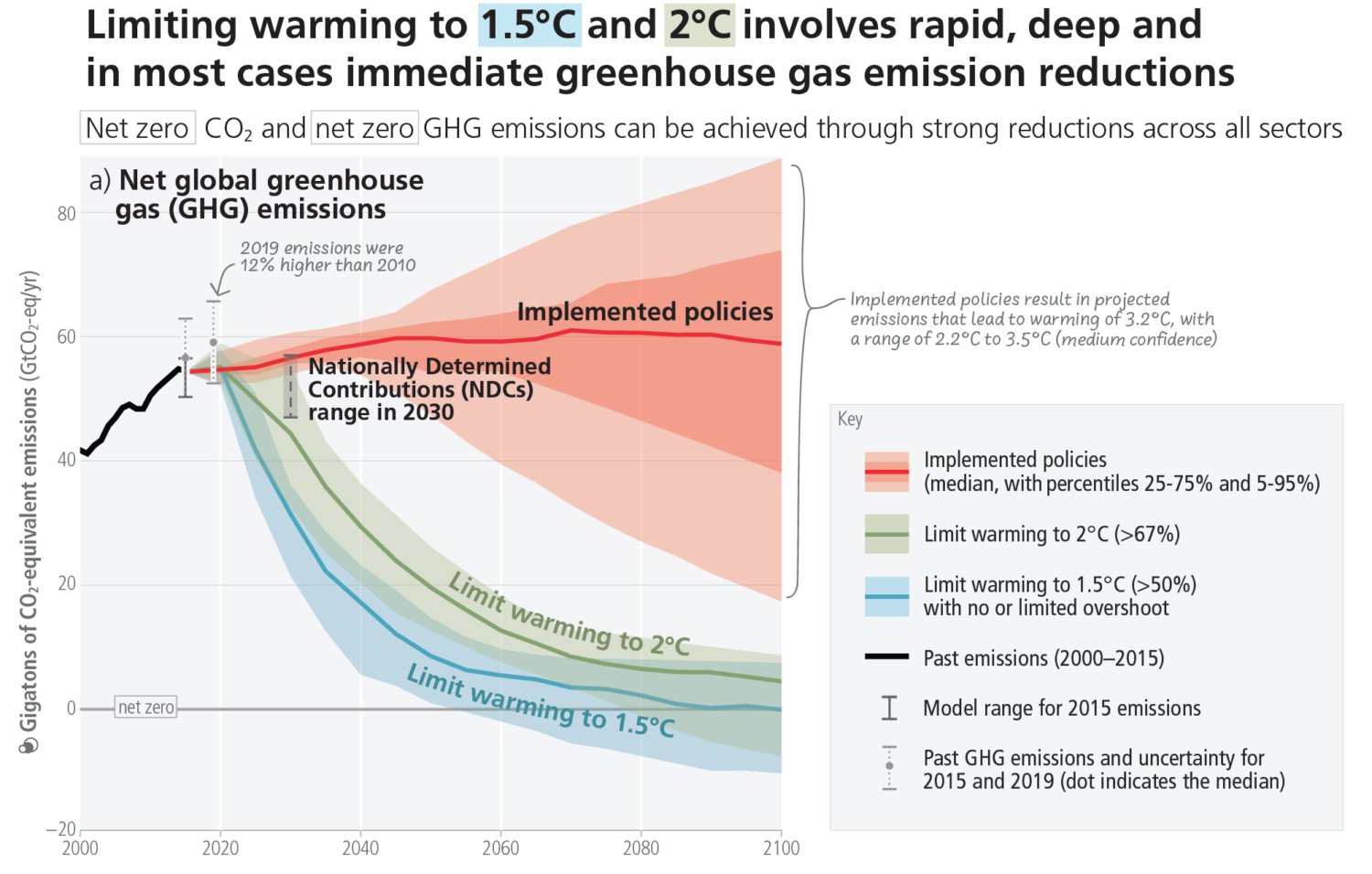

Preventing 1.5°C warming is still possible, IPCC scientists say, but only if emissions are slashed across all polluting sectors within the next decade. That includes emissions from dairy and meat — which is responsible for at least 14.5 percent of global emissions. Time is running out to avoid the worst impacts for the most vulnerable — the window to ensure “a liveable and sustainable future for all” is closing rapidly.

The latest IPCC report follows two other significant studies for food system emissions published this month — one revealing a severe gap in media coverage of animal agriculture’s impact on food and another finding food sector emissions alone could contribute nearly 1°C to global warming.

According to a new report commissioned by sustainable food organization Madre Brava, citizens of Brazil, France, Germany, the UK and the U.S. don’t regard animal agriculture as a key driver of global warming, despite the industry causing 32 percent of methane emissions.

The report further found that climate media coverage fails to cover the connection. Between 2020 and 2022, less than 0.5 percent of climate coverage released by mainstream outlets in the U.K., U.S. and E.U. mentioned the climate impact of animal agriculture. Just 447 of 91,627 monitored news pieces included information about emissions caused by the meat and dairy industries.

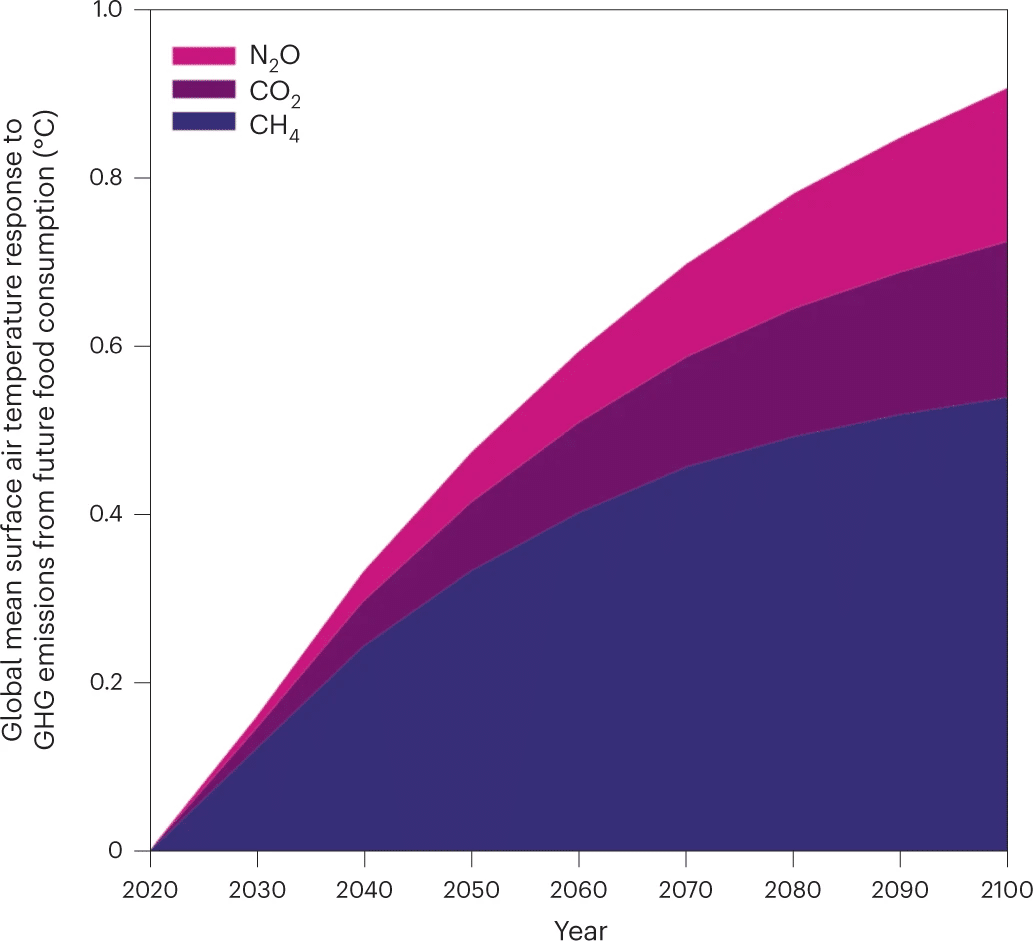

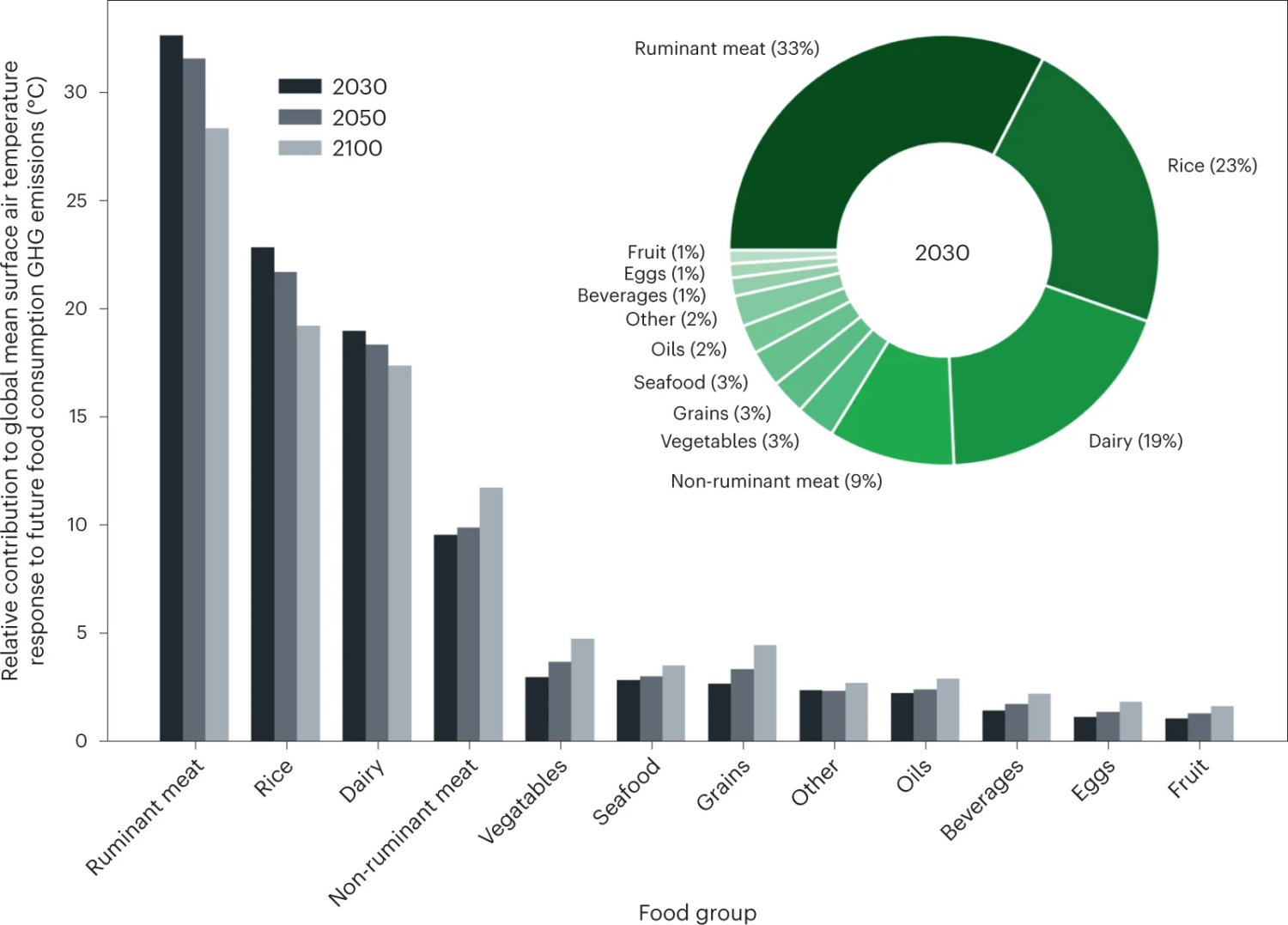

In a second study published earlier this month, researchers used climate modeling to study the impact of food emissions on global temperatures. Food sector emissions alone could add nearly 1°C to global warming by 2100, the authors write, even if emissions from other sectors were successfully reduced. The foods with the highest methane emissions are ruminant meat like beef and lamb, dairy products and also rice — accounting for 75 percent of the projected damage.

Without change to the global food system, agricultural emissions alone will add at least another 0.7°C on top of what the world has already experienced. Taken together, the additional pollution will put the 1.5 °C global climate target out of reach. Worse, this trend in the wrong direction also jeopardizes the 2°C threshold established by the Paris Agreement.

The worst offenders, according to the study, are foods sourced from ruminant animals including dairy, beef and meats like lamb. Cows emit particularly high levels of methane when they burp and exhale while digesting food, and require lots of land to raise. Animal manure is also a major source of methane — dairy and pork production are both responsible for high levels of methane emissions, according to EPA figures.

Rice also adds to the methane emissions from food thanks to soil microbes beneath flooded fields. The study suggests rice could contribute 19 percent to future warming, while all other food groups account for 5 percent or less.

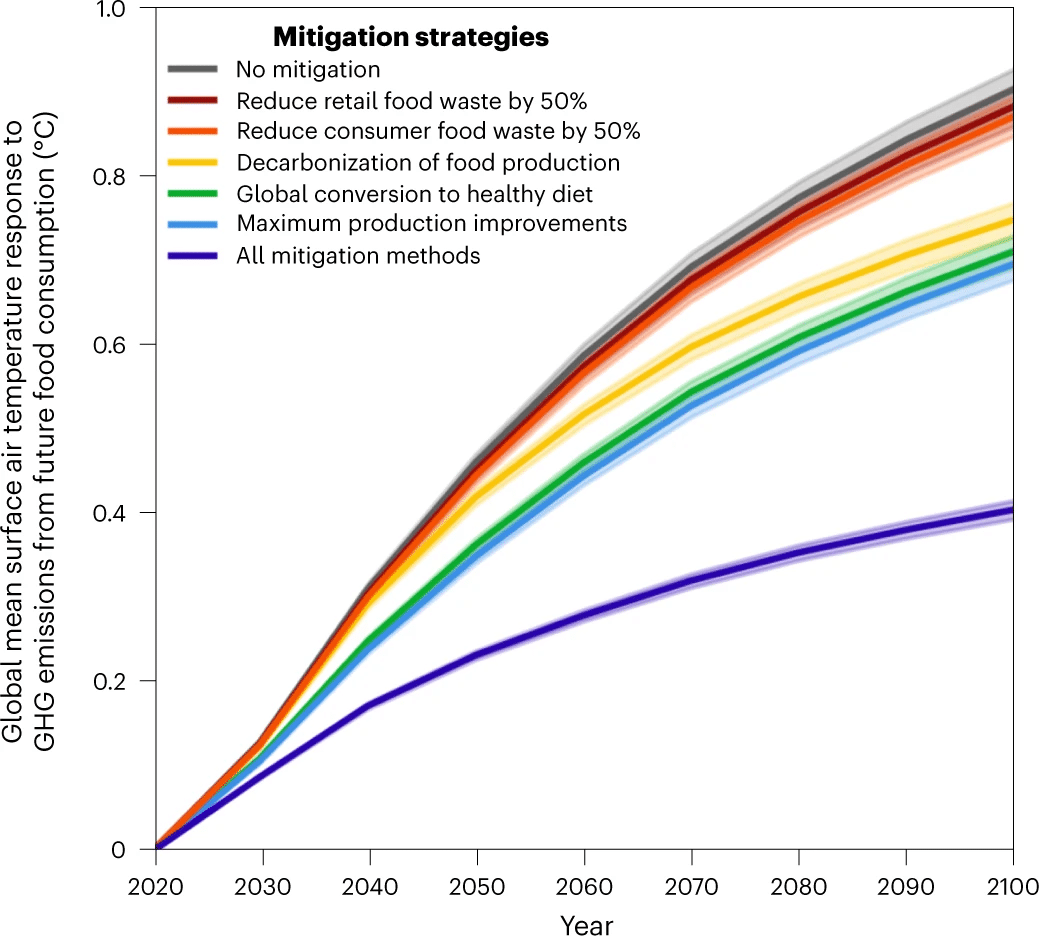

Reducing food waste, improving production practices and transitioning to healthy diets could prevent more than half of this projected pollution, according to the study.

The authors recommend an approach that centers climate-friendly diets. Motivating consumers to only eat red meat once per week and fish, poultry and eggs twice during that period, as recommended by Harvard medical school, could result in 0.2°C less warming through food emissions by 2100.

Reducing food waste, improving manure management and also using feed additives could also help reduce emissions, the authors suggest.

Both the IPCC report and the Nature study add to a growing body of evidence pointing to plant-rich diets as a crucial climate mitigation strategy.

Plant-based foods, even when processed, are more climate-friendly than meat and dairy. What’s more — according to the World Resources Institute, we can’t meet our Paris climate goals and sustainably feed a global population of 10 billion people without reducing meat consumption in favor of a plant-rich options.

Yet only one in three countries has put forward a climate plan to tackle food system emissions. To borrow reporting from our colleagues at Covering Climate Now and repeat a line from UN Secretary-General António Guterres — from this year’s Best Picture award winner — “countries must now do “everything, everywhere, all at once” to limit heat-trapping emissions.”

This piece has been updated to include more study figures and a link to the full IPCC report.