Explainer

What Is a CAFO, and Is It Different From a Factory Farm?

Food•9 min read

Perspective

Modern-day meat advertisements harken back to a time when it was OK to objectify women as body parts. In her new book, Carol J. Adams takes a closer at the role of misogyny in selling meat.

Words by Carol J. Adams

Please note this article contains expletives.

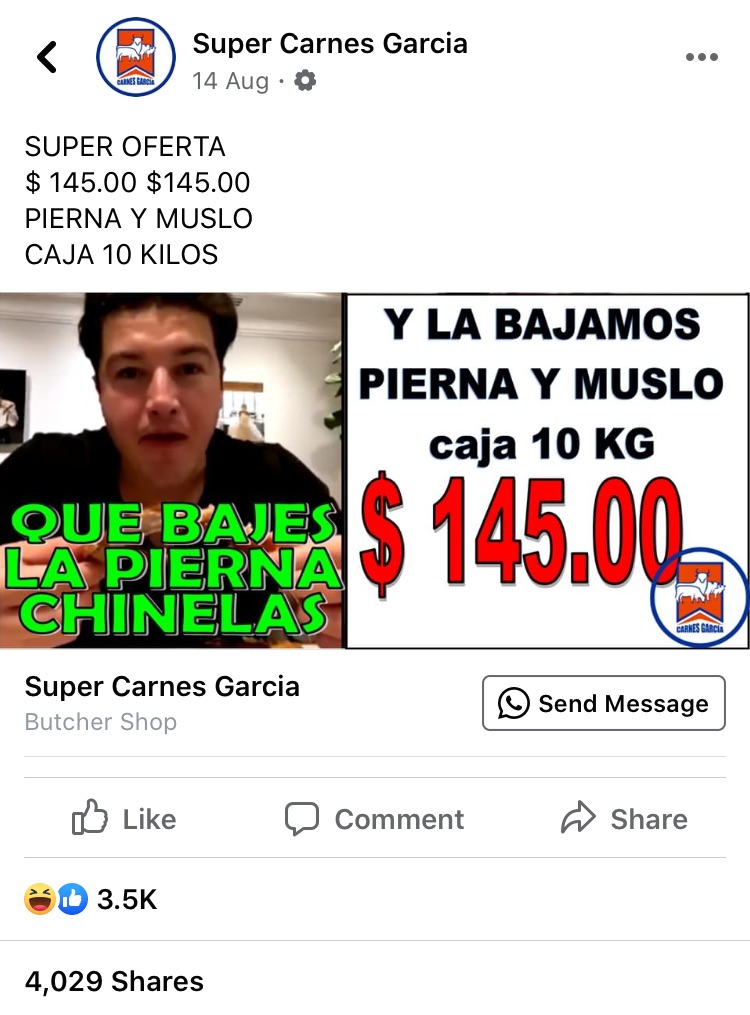

Super Carnes Garcia, a butcher’s shop in San Nicolás de Los Garza, Mexico, recently posted this advertisement to its Facebook page and Twitter account. “Lower your leg, dammit,” the advertisement says, quoting a Mexican Senator who recently said the same words to his wife in a viral Facebook video. The butcher shop invokes the words to announce that they are lowering their prices to sell dead animals’ legs.

While most of the butcher shop’s posts barely register a response, notice how many likes, laughs, and shares this one is getting.

The Senator being quoted is Samuel García, and his wife is businesswoman and influencer Mariana Rodríguez, who has 1 million Instagram followers. She also currently has COVID-19. They filmed themselves eating dinner together, apart. In the video, the savvy social media couple can be seen happily eating away, when Rodríguez raises her knee and to García appears to be showing too much “leg.” He insists, “Lower your leg dammit.”

Quickly, he was condemned for normalizing misogyny by trying to control his wife’s behavior and appearance. What is going on with such possessiveness? Of course, it raises questions about who can talk about any woman’s body. Who can talk about a married woman’s body? Who can patrol a woman’s appearance?

Many commentators pointed out how this kind of controlling behavior is often connected to domestic violence, and feminists intervened in the social media firestorm that followed to discuss how many men have murdered their partners because they viewed it as their right to control the other’s body.

But Super Carnes Garcia, a butcher shop, saw an opportunity. They quickly turned the incident into promotion, offering a proxy for control and fantasies of domination. They used the experience of an actual woman being body disciplined by her husband to sell the parts of dead animals. What a win for them! They could sell dead body parts by evoking a woman’s legs while circulating misogynist attitudes about who gets to talk about those women’s legs.

What García is criticized for, and eventually apologizes for, requires little apology when misogyny moves beyond the human species line and is instead applied to dead animals consumed as food. This is nothing new. In advertising terms, it’s called “body chopping.” For decades, sexual references have massaged dead animals’ body parts into a doubly consumable object. From queries like are you a “breast man” or a “leg man”—where the reference was dead chicken parts—to claims like those made by a supermarket in Bristol, England: “We’ve got the tastiest legs!” In that advertisement, the bottom half of a white woman’s body is shown, her stockinged legs and heels at the center of the ad, next to images of dead chickens’ legs.

Body-chopping double entendres and jokes represent humor from those who are dominant. They are the consumers, not the consumed. Once objectified, a being can be fragmented; once killed, a dead body can be cut up and sold, as body parts. This is how exploitative language moves from the whole to the part. For instance, instead of calling their victims by their given names, sexual exploiters often call them bitch, cow, or cunt. Remember “grab ‘em by the pussy?”

About that apology of Senator García’s. He recorded it on YouTube and posted it to Twitter, saying “Machismo is the cancer of Mexico. I ask you to see this message.” García called his reaction to his wife “retrograde.”

El machismo es el cáncer de México. Les pido que vean este mensaje.https://t.co/6oHHhmqAqg

— Samuel García (@samuel_garcias) August 10, 2020

Feminists, again, resisted the message, doubting the sincerity of the apology. We’ve seen apologies like that before: suddenly there appears to be an about-face, a demonstration of an awareness about women’s experiences of sexual objectification and exploitation that had been absent just hours earlier. We might rephrase these apologies down to their core, “I apologize for having made my misogyny so visible.” Where does that attitude go? That presumption of a woman’s body as property, if it is perceived as costly to express it, and yet, the desire to express it remains?

Super Carnes Garcia reminds us of the main solution that has been in place for a long time: retrograde attitudes like misogyny pivot to selling animals’ dead bodies, and in doing so escape some of the scrutiny that occurs when the same attitudes are expressed about women. Misogyny can be visible and appear not to harm anyone when it is applied to animals’ consumable dead bodies.

These attitudes hide in plain sight, promoting the misogyny but with some deniability in place: when challenged the reply is, “it’s only chickens’ legs,” “it’s only cows’ legs.” “We’re just having some fun.” They can respond this way because the dominant culture agrees—animals consumed for food are “only animals.”

What Super Carnes Garcia did was update the misogyny of body-chopping for 2020. If this had occurred a few months earlier, I would have included the image as an example of body-chopping in The Pornography of Meat due out this fall. Misogyny might have cost the Senator advancement in politics, at least at this time. But a butcher shop? In the face of faceless body parts, no one exists to be asked, “Are you okay?” Someone’s harm has become another’s pleasure, and misogynist control moves to the dinner plate, where its always been at home.