Investigation

‘You Feel Like You’re Marked’: Salvadoran Workers at Tyson Foods Face Risks Due to Work Permit Delays

Policy•9 min read

Perspective

North Carolina has been and still is a hub for some of the most restrictive and controversial laws in the country, including those favoring the animal ag industry.

Words by Jonathan Carey

New legislation in North Carolina has placed pressure on the Food and Drug Administration to review their rules regarding the labeling of milk and limits the ability of residents to hold big-ag operations accountable for pollution.

Senate Bill 711, also known as the North Carolina Farm Act of 2018 made the state the first to implement a law that would prohibit the use of the term “milk” for non-dairy products. Only beverages that come from “hoofed animals” will be able to use the magic word. If 11 other states that comprise the Southern Dairy Compact agree to adopt similar policies, the law will go into effect across much of the south. Currently, fifteen state Departments of Agriculture support the bill such as West Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina. Common milk alternatives the likes of almond, soy, and coconut would no longer be allowed to use “milk” in their labeling and be sold in states where the law is in effect.

The political clout the measure received in the Senate was viewed by many critics as a push by politicians to make the Food and Drug Administration enforce their rules on what can be called milk. North Carolina Agricultural Commissioner Steve Troxler said to Legal Newsline after the bill became law despite being vetoed by Governor Roy Cooper (D), “The FDA has not taken aggressive action in ensuring the term ‘milk’, as a standardized food, has been properly used on food labels.” After the veto, the Senate voted to override the governor.

Message received. Just weeks after the passing of 711, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb announced at the POLITICO Pro Summit that the administration would begin clamping down on use of the term “milk” on non-dairy products, telling the audience that an “almond doesn’t lactate.” Gottlieb noted that the process to change guidelines would not be quick and could take up to a year to complete.

Since 2012, non-dairy milk sales have gone up 61%; over that same time-span dairy milk sales have fallen 15% and continue to plummet. Lawmakers have tried to slow the growth of non-dairy milk on behalf of dairy producers for years.

Ryke Longest Director of the Environmental Law and Policy Clinic at Duke University has followed agriculture legislation in North Carolina for decades. He felt the move was exclusively done to make a splash on the national level.

“It’s not a significant industry in terms of size or dollar value of products sold,” says Longest about the state’s dairy industry. North Carolina doesn’t crack the top ten in dairy producing states. For all the linguistic gymnastics the bill does to aide the dairy industry, they aren’t the sole commercial agriculture benefactors of the controversial legislation.

North Carolina lawmakers have a rich history of relaxing regulations and writing favorable laws for the industrial farming complex. Another addition to the bill made Smithfield Foods the real winner of the day.

The amendment will change how nuisance lawsuits are handled across the state for years to come. These lawsuits are aimed to protect home and other property owners seeking the right to enjoy their land. They stand as a major roadblock to the monetary interest of industrial agriculture.

Since 2014, several dozen of these lawsuits encompassing 500 plaintiffs have been inching through the North Carolina courts. Residents are targeting the state’s industrial hog monoliths: Murphy-Brown and their parent company, Smithfield Foods.

Those living in hog country have complained for years of horrible odors emanating from manure lagoons used to house waste, in conjunction with the spraying of hog feces as fertilizer that also coats their cars and houses and has affected their right to enjoy their property. This has also put them at odds with lawmakers looking to protect the entrenched pork industry.

The rules in Senate Bill 711 are better known as “Right to Farm” laws. Their purpose is to significantly limit residents’ ability to file nuisance lawsuits against farming operations and are present in all states, but stricter in those where livestock and agricultural production equates to big business. Now for claims to be heard in North Carolina they must be filed within a year of an agriculture or forestry operation on which the complaint is focused, or within a year of “fundamental change.” But no punitive damages can be awarded unless the farmer has a criminal charge or has violated state farming rules.

The measures in Senate Bill 711 are better known as “Right to Farm” laws. Their purpose is to significantly limit residents’ ability to file a nuisance lawsuit against farming operations and are present in all states, but stricter in those where livestock and agricultural production equates to big business.

Furthermore, the law forbids local governments from passing new ordinances that would make farms change how they operate. Plaintiffs can also be forced to pay a lawyer and court fees if a judge or jury rules the complaint was made maliciously.

The set of decisions came into effect just months after the first lawsuit launched against Smithfield came to an end. This April, ten residents of Bladen County representative of the first lawsuits against Smithfield were awarded $50 million in damages by a jury. Individually they were to receive $75,000 in compensatory damages and $5 million in punitive damages.

Those payouts were immediately reduced to $225,000 per person due to previous legislation that states punitive damages must be limited to three times the amount of compensatory damages in the state. These rules also no longer considered the “quality of life” in nuisance lawsuits.

This isn’t the first time state lawmakers took extreme steps to protect industrial agriculture and livestock entities.

In 2016, North Carolina passed some of the toughest Ag-Gag laws in the country. Laws designed to stop activists from drawing attention to the misdeeds of a livestock operation. Anyone caught filming and/or distributing material obtained from a factory farm facility could be criminally prosecuted and face a hefty fine for each day filmed. The law was then extended to include facilities such as nursing homes and daycare facilities.

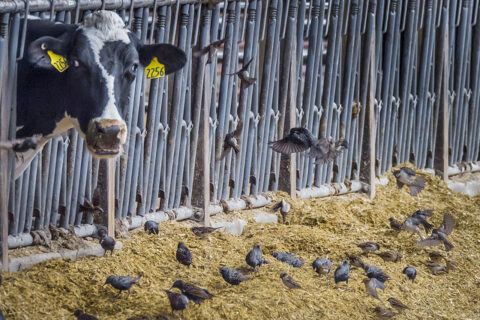

Obtaining videos like this graphic example captured by Mercy for Animals in 2015 is now criminalized under North Carolina’s Ag-Gag laws.

To understand why North Carolina has become a petri dish of laws put in place to support industrial agriculture, you have to account for the massive growth of the state’s hog industry—and the healthy dose of politics pumped into it all.

The Tarheel state’s economy thrives off the rumps of hogs. Around 9 million pigs are kept in eastern North Carolina where they outnumber humans. According to NC Family Farms, a lobbying powerhouse, the industry is worth $2.5 billion, with a total economic impact of $9 billion.

The ascension of industrial hog farming in North Carolina began in the early part of the 1990s. Representative Pricey Harrison (D), who heads environmental issues in the statehouse says this is thanks to Democratic senator Wendell Murphy—the force behind Murphy-Brown farms.

“Generally, people perceive agriculture issues to be a partisan issue, unfortunately, but I do think it was unusual for our state to have Democrats in control pushing some of these policies to protect agriculture at the expense of public interest, and this started back in the 1990s but probably goes back further.” Harrison further explained that Murphy took numerous steps to cripple counties’ ability to pass zoning ordinances against hog farms while pushing legislation that provided hog farmers with tax breaks worth millions.

The political moves initiated a boom in the pork industry. Hog operations, particularly Murphy Family Farms, began sprouting up across the state’s landscape as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) became the default of American farming. Growth occurred so rapidly that in 1997 a moratorium was placed on the construction of new hog operations in the state. Alas, to work around this, existing farms simply expanded in size and consolidated.

When Smithfield Foods purchased Murphy Farms for 11.1 million shares in 2000, loads of pork dollars and lobbyists flush with cash grabbed hold of state politics. One such lobby group, the industry-backed North Carolina Pork Council has donated around $90,000 to state candidates. That influence has consistently grown over time.

“The animal agriculture industry in North Carolina has gotten much larger with a bigger concentration of political influence and a bigger out of state presence,” says Longest.

It’s no surprise that sponsors of the bill, Senator Brent Jackson (R) and Rep. Jimmy Dixon (R), along with House Speaker Tim Moore (R), House Rules Chairman David Lewis (R), and House Majority Leader John Bell (R) all received donations this past year from Smithfield Foods’ powerful political action committee.

“The nature of the politics around animal agriculture has become much more partisan politically and the current majority in the North Carolina legislature has very much bought into that,” explains Longest. Almost all North Carolina Republicans in the Senate favored the bill.

After Smithfield sold to Chinese conglomerate WH Group for an unprecedented $4.7 billion in 2013, the North Carolina hog industry became an international commodity and a corporate giant in the state. This continues to make the ongoing lawsuits even more problematic for lawmakers, as Smithfield has threatened to take business elsewhere if litigation continues.

North Carolina has been and still is a hub for some of the most restrictive and controversial laws in the country, from voter identification requirements to legislation hindering the governor’s power. So perhaps it’s easy to see why the state’s conciliatory measures toward the agriculture industry often go overlooked. Yet, they have broad implications that affect the entire country—from what we can call and label products— to our private property rights. North Carolina is a prime example of industrial dollars influencing our laws.