Feature

Dairy and Meat Industries Push for Access to H-2A Farmworkers While the Trump Administration Slashes Their Pay

Policy•13 min read

News

The Keep Finfish Free Act would require Congressional approval for commercial aquaculture facilities.

Words by Seth Millstein

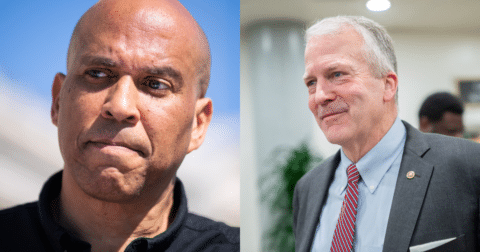

At the end of April, two U.S. senators introduced a bill that would crack down on commercial fish farms in federal waters. Sens. Cory Booker and Dan Sullivan of New Jersey and Alaska, respectively, are co-sponsors of the Keep Finfish Free Act, which would require the construction of any finfish farm to first be approved by Congress. The move comes weeks after President Trump moved to expand commercial fishing into previously protected marine environments.

“If passed, the Keep Finfish Free Act would check the corporate-driven expansion of intensive fish farming in federally managed waters, thereby protecting our coastal communities and the marine creatures that depend on healthy oceans,” James Mitchell, legislative director at the nonprofit Don’t Cage Our Oceans, told Sentient in an email.

“Industrial finfish aquaculture operations are like underwater factory farms, polluting our oceans and spreading potentially deadly diseases and parasites to wild fish,” Booker said in a press release announcing the bill. “These operations use millions of pounds of wild fish to feed the caged fish at an unsustainable rate of consumption that depletes marine resources in traditional fishing areas.”

Booker and Sullivan released the bill shortly after President Trump announced sweeping plans to reassess, loosen and remove federal restrictions on fishing operations in federal waters, and separately, to allow commercial fishing in the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, a protected area established by George W. Bush in his final days as president.

Sentient has asked the senators’ offices whether their bill is a direct response to the president’s decision, but as of this writing, they’ve yet to reply.

Booker and Sullivan’s bill would only apply to finfish, as opposed to mollusks or other shellfish. It was praised by environmental groups, with the nonprofit Friends of the Earth calling it a “common-sense approach” and Clean Ocean Action saying that “the last thing our ocean needs is industrialization,” stressing the need for “strong laws to ensure our ocean is clean and healthy for all to enjoy today and for future generations.”

Let’s take a closer look at why the bill matters.

Broadly speaking, there are two different ways of procuring and killing fish for human consumption: hunting and catching them in the wild, or farming them in constructed facilities, à la livestock. Though the terminology is sometimes used inconsistently, areas in which fish are wild caught are generally referred to as fisheries, while on-site fish farms are referred to as aquaculture operations.

For most of human history, wild caught fish greatly outweighed farmed fish on a worldwide basis. But fish farms steadily gained steam at the end of the 20th century, and since 2012, more fish have been reared in aquaculture operations than caught in the wild.

However, this disparity is almost entirely due to widespread fish farming in China, India and Indonesia; in the United States, around 90 percent of fish are still caught in fisheries, not fish farms.

Booker and Sullivan’s bill aims to limit commercial aquaculture operations in what’s called the “exclusive economic zone” (EEZ), or all waters within 200 miles of America’s coastlines. It would not ban these finfish operations directly; rather, it would prohibit the federal government from authorizing the construction of any such facilities without first obtaining Congressional approval.

If the bill passes, it could imperil Trump’s recent moves to expand fishing operations in federal waters, which were disparate and far-reaching but have largely not yet taken effect.

Trump’s orders concerned both fisheries and aquaculture operations. While the Keep Finfish Free Act wouldn’t impact the former, its passage would effectively preclude Trump from opening up federal waters to the latter without first obtaining approval from Congress.

In 2021, the Army Corps of Engineers issued Nationwide Permit 56, which gave nationwide approval for the construction of industrial finfish aquaculture facilities — fish farms, that is — in federal coastal waters. This prompted a lawsuit from a coalition of environmentalists, fishers, food safety advocates and Indigenous tribes, who argued that the corps didn’t have the legal authority to issue such a blanket authorization.

The courts agreed, and in 2022, a federal judge struck down Nationwide Permit 56 as unlawful. Because of that ruling, all potential fish farm operations in federal waters must be approved on an individual basis. The Keep Finfish Free Act would prohibit federal agencies from approving any such projects, and would instead require Congress to approve them on a case-by-case basis.

The lawsuit and the proposed Senate bill prompt the question: Why is there so much opposition to finfish farms in the first place?

Industrial fish farms are incubators for disease. As with livestock and farmed land animals, fish in industrial aquaculture operations are packed together much more densely than in their natural habitats; not only does this facilitate the spread of disease within the farms, but because water drifts freely between the farms and the oceans around them, these pathogens can spread to wild fish as well.

When wild fish get sick or die from diseases that incubated in nearby fish farms, this decreases the amount of fish available to coastal communities that rely on fishing to feed themselves. Sullivan mentioned this in his press release announcing the bill, noting that fish farms “undermine Alaska’s coastal fishing communities” and pressing the importance of “maintaining the sustainability of our world-class fisheries.”

Because disease is so rampant in fish farm conditions, farmed fish are routinely given antibiotics in an attempt to keep them healthy. However, this has led to the evolution of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, a growing and serious public health threat that kills an estimated one million people every year.

A similar problem results from the overuse of pesticides in fish farms. A common pest in aquaculture is salmon lice, a parasite that affects not only salmon but also Arctic charr and several species of trout. While pesticides were initially successful in reducing its prevalence in fish farms, the parasite gradually developed a resistance to multiple different pesticides, and a 2023 study found that salmon farms were largely responsible for accelerating this resistance.

Fish that live in the cramped conditions that fish farms confine them to tend to be far less healthy, as well as deprived from engaging in many of their natural behaviors. In addition to suffering high rates of infections and parasitic diseases, fish in industrial aquaculture operations experience immense stress, and farmed salmon have even seen exhibiting symptoms of clinical depression. A significant body of scientific studies have found that fish do feel pain, and undoubtedly suffer in fish farms.

At this point, it’s difficult to say what the Keep Finfish Free Act’s prospects for passage are. It’s a modified version of an identically named House bill that the late former Rep. Don Young introduced in 2021; while a House subcommittee did hold hearings on that earlier bill, it was never scheduled for a full vote.

That doesn’t necessarily mean this version is headed for the same fate, however. The makeup of Congress is different now than it was in 2021, and the recent court decision against the Army Corps of Engineers bolsters the argument that federal agencies have been too permissive in approving industrial fish farms. There is also at least some appetite for criticizing industrial agriculture as a result of RFK Jr.’s role in the administration, so that may play a role too in garnering support.

As it stands, commercial aquaculture only accounts for a small fraction of seafood in the U.S. — and if the Keep Finfish Free Act passes, it’ll go a long way to ensuring that this remains the case.