Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Feature

The Trump administration has cut funding for diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives as part of an effort to reduce what it deems wasteful spending.

Words by Sky Chadde, Investigate Midwest

This story was originally published on Investigate Midwest.

In Vicksburg, Mississippi, the south end of town near the municipal airport has no grocery stores, no food pantries. Mired in a federally recognized food desert, nearby families struggled to obtain healthy food. Then, in 2019, in a once-empty lot, a community garden sprouted. Families could pick their own blueberries, peas and okra.

The nonprofit behind the garden, Shape Up Mississippi, aimed not only to address food insecurity in the predominantly Black neighborhood but also to promote the agriculture profession to children through an annual event. Farmers gathered at the garden to showcase their equipment, and local U.S. Department of Agriculture employees taught kids about soil health.

But Shape Up had to cancel the event this year, and for the past several months, it’s limited the number of days residents can harvest. Last year, it received $10,000 through the USDA, but the grant was unexpectedly axed in February. Shape Up was forced to curtail services.

Linda Fondren, Shape Up’s leader, said losing the grant will particularly hurt young mothers who relied on the green space. “All of a sudden,” she said, “they found something that was working for them, and then it got taken away.”

Shape Up’s garden was caught in the political crosshairs of a dramatic shift at the USDA. Since assuming power, the Trump administration has cudgeled what it deems “wasteful” spending on projects related to diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI. Shape Up’s community garden, which serves a community that is three-quarters Black, qualified.

The USDA’s purge has resulted in a significant loss of funding for programs increasing access to fruits and vegetables, and some creating pathways for more Americans to enter an industry with rapidly aging farmers. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins has claimed the USDA has ended more than $148 million in DEI funding, though who has been affected is difficult to verify because Investigate Midwest’s request for a detailed list has not been fulfilled.

The concept of DEI is intended to promote practices, mainly in the workplace, that address systemic discrimination against racial and gender minorities. The Trump administration has used it as a blanket term for funding that benefits minorities. For instance, in March, Rollins explicitly tied canceled funding to gender, saying a program — she didn’t specify — was cut because it was for “food justice for trans people in New York and San Francisco.” In July, the USDA said it would end race and gender-based financial support.

Targeting DEI is a “red herring,” said Thomas Burrell, the president of the Black Farmers & Agriculturalists Association. “It speaks volumes, to me at least, that you intend to continue to discriminate against Black farmers.”

The USDA did not respond to several requests for comment sent over the past several weeks.

Some organizations that lost funding did not return requests for comment, including one that feared doing so would jeopardize future grants with the USDA.

The effort to eliminate DEI funding could impair one of Rollins’ goals: recruiting more farmers.

The average age of farmers, 58 years old, concerns her, she said at her confirmation hearing. “If we really think we will have a sustainable, thriving agriculture community in 20 or 30 years after we have gone to meet our maker, we have to reverse that trend,” she said.

But cutting off support for minority farmers could create more barriers to those interested in agriculture, said Michaela Hoffelmeyer, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has studied the agricultural workforce.

“It’s counterintuitive to not invest in this group of farmers because these people are farmers, first and foremost, regardless of their race, gender, sexuality,” Hoffelmeyer said. “I think it does raise some questions about if we’re really supporting all farmers and what that means long-term for our food supply.”

The cuts also likely affect endeavors Rollins has vocally supported. Organizations with canceled funding helped connect community members with small farms, promote the purchase of locally grown fresh fruit and vegetables, and push healthy lifestyles. Access to healthy food is the ostensible desire of the Make America Healthy Again movement, and Rollins has described herself as a “MAHA mom.”

The administration’s efforts have already had a chilling effect internally. Charles Dodson, a recently retired civil servant who studied racial disparities in department lending, believes his former team at the USDA is now too fearful to communicate with him. After Trump assumed office, he said, he tried to contact his former colleagues to check on their progress. Just one answered, to say they were keeping their head down.

Ike Leslie, a berry farmer and researcher based in Vermont, has been hit particularly hard by the USDA’s cuts. In 2023, Leslie, who is queer and trans, won a large USDA research grant, but the money was frozen for months until early September. To receive the funding, they had to remove all references the administration defined as DEI.

Leslie also had a $45,000 climate resiliency grant canceled. The Biden administration created a program to reward climate-smart practices on mostly small farms, the kind that queer farmers and farmers of color typically operate. But the Trump administration ended the program.

The defunding has set their farm back years, Leslie said. They’ve had to delay buying new glasses and new tires for their pickup truck.

“I’m avoiding health care and other costs,” they said. “This is the reality that we’re in. When you take people’s bread, they suffer.”

On Jan. 20, Trump’s first day back in office, he signed an executive order ending support for DEI training and staff positions. Having a “chief diversity officer” or an “equity action plan” amounted to “immense public waste and shameful discrimination,” the order stated. “That ends today.”

Days later, staff in the USDA’s finance office began searching for DEI-related grants to terminate. When Rollins took over Feb. 13, she directed staff to prioritize “merit” and “color-blind policies.” Any funding that appeared to contradict her directive was reported to her office, according to court records.

By the department’s own admission in legal filings, a broad brush was used to define “DEI.” By April, the USDA had frozen funding for more than 300 projects. However, after a judge’s injunction, the USDA was forced to release some money. In early May, the USDA told the court that only 34 projects remained “frozen for DEI.” (The case is ongoing.)

More cuts followed, however. In mid-June, Rollins announced that “more than 145 awards,” totaling about $148 million, were canceled. “Putting American Farmers First means cutting the millions of dollars that are being wasted on woke DEI propaganda,” Rollins said in a press release.

The administration has also attempted to import white farmers to the U.S. Trump has falsely claimed white farmers in South Africa, which used to operate a brutally racist system of apartheid, are facing a “genocide.” Then, the administration created a refugee program, which a political appointee acknowledged privately was intended just for the country’s white people, according to Reuters.

Rollins has decried the mere mention of race or gender. Before becoming agriculture secretary, she chastised the “race-obsessed press” for commemorating the first time Black quarterbacks faced each other in the Super Bowl. Historically, Black players were not deemed smart enough to play the game’s most valuable position.

Early in her tenure, Rollins singled out tomato seeds as evidence of DEI’s purportedly insipid creep into society. In a video posted to X, she showed seed packets adorned with the phrase, “Growing diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility at USDA.” With a concerned look, Rollins said, “This is what we’re fighting.” She then threw the packets in a trash can.

A day later, on a conservative radio show, Rollins cast blame on the Biden administration. “I guess they thought tomatoes were racist,” she said.

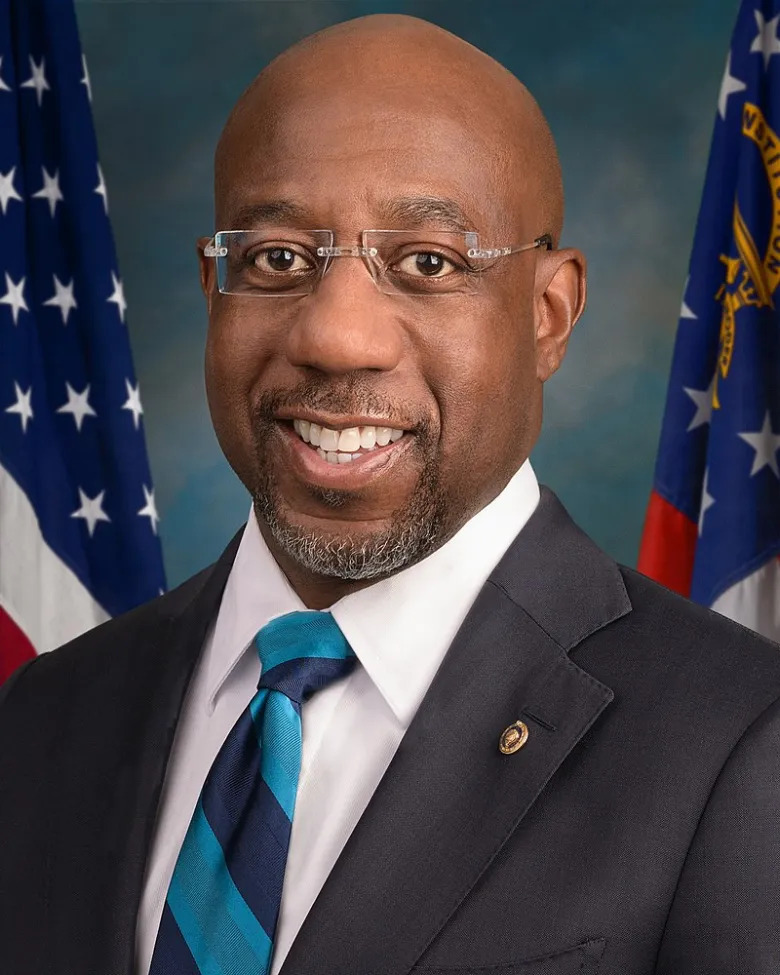

Rollins has also dismissed diversity efforts related to hiring. During her nomination hearing, Sen. Raphael Warnock, a Georgia Democrat, asked her if she’d commit to recruiting more Black employees. Rollins did not answer directly and said she’d recruit the “best workforce in the history” of the USDA. (All of her high-level political appointees are white.)

At other times, she’s said USDA hiring is now a “meritocracy.” At a June hearing, U.S. Rep. Joshua Jackson, an Illinois Democrat, asked her if the department had a written definition of merit. “I am not aware of that,” she replied.

One person who appeared to have significant influence over USDA decision-making was Gavin Kliger, a DOGE operative who spearheaded funding cuts. Kliger’s resume shows no agricultural experience, and in emails to staff, he demonstrated a misunderstanding of how critical soil health is for farmers. Kliger has also promoted white supremacist and misogynistic content on X, according to Reuters.

The USDA’s history of denying support to farmers of color long predates the current administration.

In the 1930s, the department facilitated the creation of county committees that voted on how to disperse federal funds, which essentially guaranteed white farmers benefited. The system earned the USDA the nickname “The Last Plantation.” (The system still exists. In 2023, the USDA released a report finding that, because minorities were often excluded from serving, the committees “often cripple the economic livelihood of minority farmers.”)

In 1999, in the landmark Pigford v. Glickman case, a judge ruled the department denied loans to Black farmers because of their race and ordered restitution. In 2010, a second round of restorative payments were issued. In both cases, the USDA did not admit its discrimination.

After Pigford, a series of lawsuits alleging USDA discrimination against women, Native American and Hispanic farmers followed. In 2011, the department announced a plan to resolve the claims.

Under President Obama, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack pushed a narrative that the department was addressing systemic racism. For instance, the USDA claimed the number of Black farmers had increased between 2007 and 2012. According to an investigation by The Counter, a newsroom focused on agriculture and food, the figures were misleading.

Internally, race was a third rail, regardless of which party controlled the White House, said Dodson, the recently retired USDA civil servant who started his career at the agency in the mid-1990s.

In 2013, he published a paper examining the USDA’s role in lending disparities. His analysis showed Black farmers typically have worse credit histories than white farmers — a result consistent with systemic racism — that hindered their eligibility for federal loans. When examining several years of data, he concluded there was “no evidence” of prejudicial behavior by USDA.

Still, he said, his superiors yelled at him. “The pushback was so extreme,” he said. “It took me aback.” He dropped further inquiries.

When Trump was elected the first time, the USDA’s lending program disproportionately backed white male farmers. Between 2017 and 2021, the department rejected fewer loan applications from whites, according to data obtained by CNN. At the same time, the department rejected far more loan applications from Black, Asian and Hispanic farmers.

The first Trump administration also targeted young queer people interested in farming. In 2018, Trump officials pressured 4-H, a youth organization for beginning farmers, to drop a proposal welcoming LGBTQ members, according to the Des Moines Register. A 4-H leader in Iowa who supported the proposal was fired.

When Biden was elected, he placed more emphasis on race and gender. Dodson formed a team to research racial disparities, and in 2021 USDA surveyed, for the first time, agricultural producers’ sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act into law, which created the Discrimination Financial Assistance Program to directly pay Black farmers. (A group of white farmers contested the program in court.)

Overall, though, the USDA has struggled to reckon with racial disparities. Once, during the Biden administration, when reviewing a study from another department agency about minority farmers, Dodson said his supervisor resisted its conclusions. When he asked why, the supervisor replied, “I just don’t think Black farmers are very good managers.”

Dodson, like many USDA employees, grew up in rural America, and he heard similar comments. “You’ve got a culture at USDA that reflects that attitude,” he said.

The effects can be felt on the ground. For Black farmers, attempting to get a loan from the USDA is like trying to negotiate in a different language, said Tiffany Bellfield El-Amin, the leader of the Kentucky Black Farmers Association.

In recent years, more of her members have begun building a relationship with the local office of the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, which helps farmers maintain soil health, she said. The uptick correlates with a Black representative being available.

As part of the USDA’s DEI initiatives, the representative worked to establish cooperative agreements — for instance, the USDA might partner with a historically Black college to increase land access — that brought more Black farmers into the fold.

“There’s a big language barrier between Black folks and these agencies,” she said. “I’m going to say this respectfully: I think folks in office know there’s a barrier and sometimes do not go outside themselves, which is why we have these DEI initiatives.”

John McCracken contributed to this story.

This article first appeared on Investigate Midwest and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.