Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Solutions

Shinkei blends new technology with Japanese tradition in hopes of sparing fish a painful death.

Words by Grace Hussain

In California, a tech startup is looking to blend AI with an ancient Japanese slaughter method in hopes of improving fish welfare and sustainability. Called Ike Jime, which means “brain spike” or “closing of the fish,” the practice kills fish more quickly and with less pain, when performed correctly. Better welfare also stands to benefit the company’s bottom line: fish slaughtered this way stay fresh longer, which could help cut back on waste and spoilage.

Sometime between the early 1600s and the mid 19th century, fishers in Japan started using the method, which involves driving a spike through the fish’s brain, quickly ending their life. A popular slaughter method in Japan, Ike Jime has since spread across the globe, growing in popularity amongst sportsmen in the United States and garnering the praise of the Michelin guide.

Up until now, Ike Jime has been primarily a hand-slaughter method. “People have been trying to automate this technique basically since the 1970s,” Saif Khawaja, CEO of Shinkei, tells Sentient. But earlier machinery could not accommodate the variation in fish size and shape, which meant one type of machine couldn’t be used to slaughter different types of fish. Now, Khawaja and his team say they have found a solution in AI, and so far it’s working — albeit on a small scale. Shinkei has dozens of customers, and hopes to expand as it improves the model.

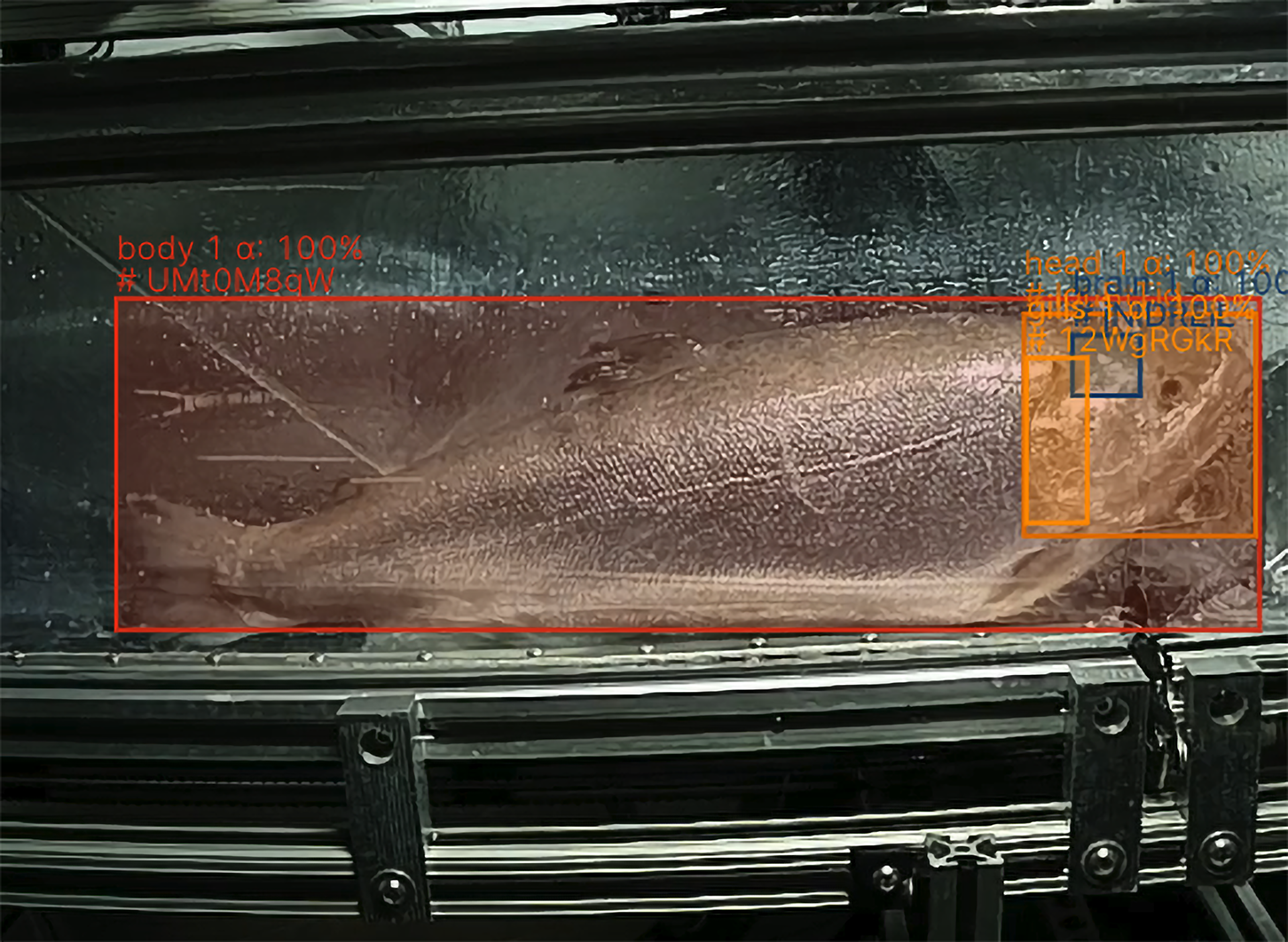

Here’s how it works: the system uses artificial intelligence to detect the size and shape of each fish, and then use that information to identify the location of the brain. The mechanical component — the technical details of which the company does not want to reveal — then penetrates the brain, taking just a second of time.

Michael Fabbro, CEO of LocalCoho — a salmon farm in New York State that has been using the Shinkei system — has been impressed with the system’s precision. According to Khawaja, the system kills with its first strike 98 percent of the time. “The computer vision is really [what] gives us that surgical accuracy,” he says.

When performed correctly, the Ike Jime method kills fish in about a second once spiked — significantly less than most other methods of slaughter for farmed and wild caught fish. “In some species, it can take up to 15 minutes for fish to die in air or ice water, and that’s a really long time to suffer,” says Lynne Sneddon, PhD, a lecturer at University of Gothenburg who has researched fish pain for more than two decades.

Most fish experience very painful deaths, Sneddon tells Sentient, and this “very rapid” method of killing is an improvement over alternative methods that leave fish to suffer for minutes on end.

A combination of factors — improved animal welfare and better filet quality — attracted Fabbro to adopt the system at LocalCoho. The two factors are intrinsically connected, as when fish are stressed and thrashing — as is the case with most slaughter methods — their collagen breaks down more quickly, which softens their flesh and leads to a shorter shelf life. Restaurants and grocery stores have to toss spoiled fish, missing out on profits and adding to food waste.

For most foods, how they are transported doesn’t make much of a difference for climate pollution — as transportation in the food sector only makes up six percent of emissions, and most foods are not flown to their destination. But it can make a difference for the few foods that are air-freighted, which includes fresh fish, as these air-freighted foods can have a 50 times greater emissions footprint. With the Shinkei system, producers may be able to ship rather than fly the fish, which would offer some greenhouse gas emissions savings.

“When you package [the fish] and put it in a fridge, you have a longer time to sell that piece of fish because it doesn’t deteriorate too quickly,” says Sneddon. Though the specific shelf life varies based on fish species, filets slaughtered using Ike Jime can stay firm for four or five days — often long enough to be shipped via boat depending on origin and destination.

Shinkei doesn’t sell the systems but operates in partnership with fish producers. The model is this: as fish producers grow and generate more income, so does Shinkei. “Our partners get most of the upside, and we scale with them,” says Khawaja of the arrangement, though the exact cost share depends on a variety of factors, such as the type of fish and how many are being processed.

LocalCoho is one of those partners, now using the 3.0 version of the automated Ike Jime system. When Michael Fabbro joined the farm in 2022 as CEO, the company slaughtered its salmon using standard industry methods, which he says caused the fish “a lot of thrashing about and a lot of stress.”

Fabbro initially looked into traditional techniques like Ike Jime, but worried about staff injuries. One of his customers introduced him to Shinkei. And at first, Fabbro’s workers were skeptical, but a month of training helped them feel more confident in using the technology. Since then, Fabbro says the system has improved “our quality, our consistency and our market.”

His staff is no longer handling thrashing fish and knives, he says, which means lower risk of physical injury and a better end-of-life for the fish. There might be other types of health benefits too, for his staff. Fabbro points to the huge toll that slaughtering animals has on worker mental health, and hopes that the more humane method will be better.

Since the company’s founding in 2021, the systems have been used to slaughter 25,000 pounds of fish — which for now, is a drop in the bucket compared to the hundreds of thousands of fish killed daily. The system isn’t made to handle larger, industrial fishing vessels or fish factory farms, but the company has been working on improvements to the model.

A new 4.0 version of the system is slated for release later this summer, which Shinkei’s CEO, Khawaja, says will increase the speed and thus capacity of the machine. One way to do that is to eliminate the need to handle the fish at all. Right now Fabbro estimates that the entire slaughter process takes 10 to 15 seconds per fish. Most of that time is spent catching the fish with a net and placing them into the machine. That’s one step of the process that Khawaja and his team are trying to cut.

Handling the fish at all stresses out the fish. It’s a problem Khawaja is trying to solve with the system’s next iteration. We’re working on “having a deal with the fish [go] straight from the finishing tank directly to the robot so that it really gets hands free,” says Khawaja.

Once those updates have been implemented, the startup hopes to get the technology into the hands of more fishers and fish farmers. “We’re really trying to just get this ready for manufacturing,” says Khawja. If successful, the company’s machine could one day be used on industrial operations, including eventually for salmon and trout, who are widely raised on industrial farms and enjoy few welfare considerations. If implemented across the industry, the system would represent a significant step for animal welfare.