News

RFK Jr.’s New Dietary Guidelines Tout Meat, but They Could Actually Open the Door for More Plants in School Lunches

Diet•8 min read

Investigation

“I am afraid that if we had tried to 'hide' what we had learned...then press found out, we would be butchered like a fat buck!”

Words by Nina B. Elkadi

Over twenty years ago, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, the Food Bank of Iowa and the Department of Corrections forged a plan. The idea was simple: hunters would hunt overpopulating deer, and the public would receive processed venison through food banks and prisons. And it worked. In 2007, more than 8,000 deer were donated to the program, feeding tens of thousands of people in the process.

In 2008, however, the program hit a bit of a road bump. Officials in North Dakota “advised food pantries across the state not to distribute or use donated ground venison because of the discovery of contamination with lead fragments.” In response, the Iowa DNR sent participating venison processors a letter. They advised the processors to “periodically check grinders for lead fragments.” But they ultimately did not begin regularly inspecting the meat, nor did they end the program. In fact, in the letter, they noted “there is no evidence linking venison consumption to lead poisoning in humans.”

Some sources Sentient spoke with speculate the National Rifle Association might have something to do with this — the organization proudly boasts their donations to “Hunters for the Hungry” programs around the country and publicly denounces attempts to ban lead ammunition.

Almost two decades after the program began, Iowa venison may still contain lead, putting consumers — particularly the youngest — at risk.

In neighboring states, like Minnesota, venison killed by shotgun is x-rayed for metal fragments before it is distributed to food banks. Meat found to contain fragments is discarded. But Minnesota is the exception. A Sentient investigation found that at least 42 states and the District of Columbia have some sort of program whereby non-profit groups or the department of natural resources donate venison to food pantries. Of those programs, only one, Minnesota, confirmed that they x-ray meat for lead and two states, Iowa and South Dakota, confirmed that their packaging discloses that there might be lead in their venison or that the venison is not tested for lead.

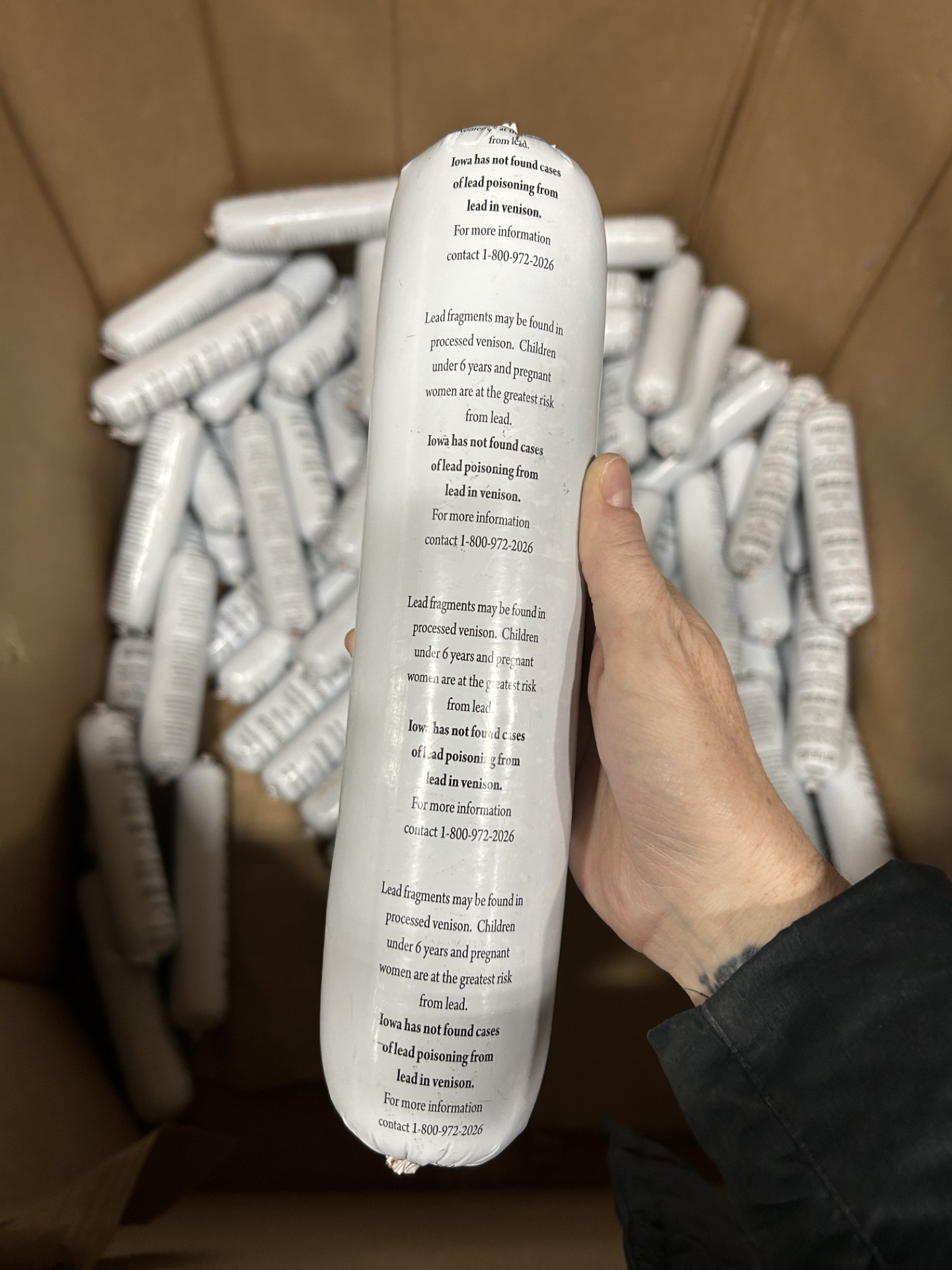

In Iowa, a warning label on the food bank venison reads “Lead fragments may be found in processed venison. Children under 6 years and pregnant women are at the greatest risk from lead [sic]. Iowa has not found cases of lead poisoning from lead in venison.”

Studies show lead contamination in venison is not uncommon. A 2020 study found that almost 48 percent of shotgun-harvested ground venison packets in a sample from Illinois contained metal fragments, all of which turned out to be lead. Another study, conducted in 2009, found that 80 percent of tested ground venison samples contained metal fragments — 93 percent of those fragments were lead. Although no lead exposure is safe for humans, and it is even more dangerous for young children, hunters still predominantly use lead ammunition for hunting.

Public health officials are well aware of the problems with lead, and have long taken steps to reduce lead exposures. For example, lead-based paint was banned from residential use in 1978. More recently in 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency announced it was requiring almost all cities to remove and replace lead water pipes within 10 years.

Not so for game meat. In 2022, University of Pittsburgh researchers did begin sounding the alarm about lead in food bank venison. “Low-income families relying on food banks are already disproportionately affected by elevated [blood lead levels],” they wrote. “Game meat donated by hunters is a source of valuable nutrients for recipients of donated food, but risks from adulteration with lead ammunition should be addressed through primary prevention. This is an avoidable dietary source of lead exposure.” These same researchers called for an end to stocking venison shot with lead bullets in food banks.

With all the evidence that any exposure to lead is bad exposure, why do so many states still allow potentially lead-laden meat to go to its most vulnerable community members?

For decades, the National Rifle Association has played a role in game meat donation programs. According to the NRA’s own website, the association “provides subsidy payments (up to $2,000) to Hunters for the Hungry processors to support their efforts.” As of 2023, they have donated over $650,000 to various state programs.

In 2011, retired nurse Cynthia Hansen was active in advocating for banning lead ammunition in mourning dove hunting in Iowa. Hansen alleges that lobbyists from the NRA came to the state to weigh in. “They said it’s the start of us trying to take away their guns,” Hansen tells Sentient.

The lead ban did initially go through, but a few months later, then-Governor Terry Branstad overturned it. Two years after that, the NRA Political Victory Fund endorsed his gubernatorial race, citing that he “led the fight to prevent state bureaucrats from imposing a statewide lead ammunition ban for dove hunting.”

This was not a limited issue, it turns out. The lobbying arm of the NRA, the NRA Institute for Legislative Action, has an entire page dedicated to “Traditional Ammunition (Lead)”. The first bullet point states:

The use of traditional (lead) ammunition is currently under attack by many anti-hunting groups whose ultimate goal is to ban hunting. Traditional ammunition does not and has not negatively impacted wildlife populations in North America and is far more effective and affordable for American hunters.

Hansen disagrees with the NRA’s characterization of the ban as against hunters. “That’s not at all what we wanted,” she says. “I have nothing against hunting. My father hunted back in the day, but we just want ethical and good environmental practices for those that do hunt. And protect your families too. Don’t take lead-infused meat home to feed your families.”

In a 2021 blog post for the NRA Hunters’ Leadership Forum, wildlife biologist Jim Heffelfinger asks “if the concern is really for the birds.”

“We certainly see cases of bird advocates exaggerating the dangers to hunters of lead bullet ingestion out of concern for bird deaths. You can’t blame them for being passionate about what they love, but we have to make personal ammunition decisions based on good science,” Heffelfinger wrote. “Unless mandated by law (as in California), a switch to nonlead ammunition is up to the individual depending on their assessment of health risk and other reasons.”

At food banks across the country, venison is often distributed in the form of packaged ground meat. In venison shot with a shotgun, “there’s a definite human health concern in consuming that venison, especially for children,” says Given Harper, one of the authors of a 2020 paper that found 48 percent of tested venison samples had metal fragments in them, all of which were lead.

“There’s no safe level of lead, and in particular, in children with developing nervous systems, I think this can have a really harmful impact,” Harper tells Sentient.

On March 26, 2008, North Dakota officials announced they found lead levels in venison exceeding the Food and Drug Administration guidelines, ultimately advising food pantries against distributing it. That next day, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources advised food banks to stop distributing venison.

In documents obtained by Sentient through a public records request, in light of the North Dakota study, then-Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Big Game Coordinator Lou Cornicelli wrote to an Iowa Department of Natural Resources HUSH assistant: “Given everything that’s going on, I wonder if anyone will have a venison donation program!” To which the assistant replied, “…good luck with this lead issue. I have full faith that this, too, shall pass.”

Cornicelli also wrote to then-HUSH coordinator Ross Harrison, of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, speculating that, “Our local paper said the Dr. is heavily involved with the Peregrine Fund, which is the group that is actively working to ban lead bullets. So, there may be more to the story …”

On March 28, Harrison emailed colleagues that Iowa would test some venison for lead. In internal emails to a colleague in Missouri, Harrison wrote: “I am afraid that if we had tried to “hide” what we had learned from ND, then press found out, we would be butchered like a fat buck!”

That same day, Kay Neumann, executive director of Saving Our Avian Resources, wrote to the department praising their quick action on pausing distribution. “Perhaps only copper shot deer should be accepted into the HUSH program?”

A DNR employee forwarded Neumann’s email to Harrison. “It’s started!” they wrote. Harrison asked that employee to look into the toxicology of copper, and another employee at the DNR wrote back with a few links and a note: “As far as I am concerned a lot of this is just pure hype so I do not want to spend a lot of time on this.”

On April 2, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources released their testing results: two of the 10 samples tested positive for lead at “an extremely low level.” The program thus resumed.

In the above letter, which was sent to meat processors in the program, Harrison wrote,

Of more importance, the Department of Health has had an aggressive lead screening for young Iowans since 1992, having tested more than 500,000 under the age of 6. When lead is detected in this screening, an investigation is conducted to find the source. There has never been a source of lead in humans indentified [sic] as coming from venison or any other wild game. On the recommendation of the Department of Health, we advised food banks to continue venison distribution and consumption.

For Jace Elliott, the state deer biologist for the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, “making sure that we get food to folks in need is a higher priority than perhaps worrying about sort of an unknown risk,” he tells Sentient.

Like exposure to many other toxic substances, it is difficult for researchers to pinpoint an exact source of lead poisoning, but there is scientific consensus that no level of lead exposure is safe, and repeated exposure causes health issues.

According to the Mayo Clinic, lead poisoning, which occurs when lead builds up in the body, is most dangerous for children under the age of six. Exposure can cause developmental delay, learning difficulties and seizures, among many other symptoms. And ultimately, because even small amounts of lead have been shown to cause injuries, government health agencies agree there is no safe level of lead in blood.

While lead detected in drinking water has attracted national media attention, potential lead in donated game meat has received far less scrutiny. Yet, a 2023 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health study found that children who live in a community where people own firearms are more at risk of elevated blood lead levels, likely due to proximity to lead-based ammunition. “Behind poverty, firearm licensure was the most significant predictor of high blood lead levels in children,” a write-up about the study says.

In Iowa, parents of children who have high elevated blood levels receive a questionnaire. The form has questions asking if the child eats paint or dirt. It also asks, “Does your family use products from other countries such as pottery, health remedies, spices, or food?”

“[The state health department] comeback was, well, we’ve never had a case of lead poisoning from eating game meat. They’ve never had that because they don’t query for that,” Neumann, executive director of Saving Our Avian Resources, and an advocate against lead ammunition in Iowa, says. “They ask about ceramics and candy and paint…but they do not query about eating game meat. And if someone got that meat from the food pantry, they might not realize that it’s game meat, and wouldn’t even be able to answer the question correctly if it were asked.”

In response, the Iowa Department of Public Health wrote to Sentient, “Iowa HHS does not collect data to determine if children with elevated blood levels [sic] have consumed game meat in general or from a food bank. The majority of cases in Iowa come from lead-based paint. Iowa HHS and DNR work together to ensure venison donated through the HUSH program is safely processed and a nutritious source of protein for Iowans in need. If parents are concerned about their children being exposed to lead, they should contact their child’s health care provider.”

Jaydee Hanson, policy director for the Center for Food Safety, tells Sentient that under U.S. law, every meat product sold needs to bear an inspection stamp from the Food Safety Inspection Service at the Department of Agriculture, certifying that it has been tested for, among other things, lead. However, wild game meat, which was proposed to be fed to prisoners in some states (the Iowa donation program once had a Prison Venison Program) and food bank consumers, is not required to be inspected by the USDA.

“Roughly 100 years ago, another investigative reporter, Upton Sinclair, talked about what was going on in the slaughterhouses of Chicago, but he didn’t include deer,” Hanson says, referring to regulations that came to the meat industry after Sinclair’s 1906 publication of “The Jungle.”

The early 1900s saw an onslaught of new regulations in the meatpacking industry, and some of those regulations, like the Meat Inspection Act, have not changed much since then. Today, nearly 99 percent of all farmed animals raised for consumption live on factory farms. Game meat, like venison, is in a category all of its own.

“We view deer and to a lesser extent, elk and ducks and other wild animals as a public resource,” he says. “When you do anything in most parts of the U.S. to regulate guns, including what their ammunition is, people get upset.”

For hunting pheasants, doves and turkeys, Kay Neumann uses non-toxic ammunition like steel, tin or bismuth. For deer hunting, Neumann uses copper. Neumann first became interested in lead in 2004, when she began seeing lead poisoning in bald eagles. Her organization scanned the digestive tract of over 500 bald eagles and found lead fragments.

Then she started x-raying venison donated to food pantries. One-third of those packages contained lead fragments.

“If an animal’s been shot with lead ammunition, there’s a good chance there’s lead in the meat that people would like to feed to their families, and no one should eat lead,” Neumann tells Sentient.

Lead is the most commonly used material for ammunition in the United States. It is overall the most common use of lead in the U.S. behind lead-acid storage batteries. Due to the composition of the ammunition, certain types, such as lead slug, are more prone to fragmentation.

According to multiple sources including the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Park Service, and the Center for Biological Diversity, lead ammunition has negatively impacted wildlife populations in North America. In 2013, the Center for Biological Diversity sent a letter to the NRA in response to the NRA requesting information about the impact of lead ammunition on condors. Center for Biological Diversity Executive Director Kieran Suckling wrote to the head of then-CEO of the NRA, Wayne LaPierre:

Perhaps this admission of ignorance explains the NRA’s long history of public statements denying the terrible toll lead poisoning is taking on America’s wildlife. It would seem that the NRA’s implausible opinions are simply based on not having researched the issue thoroughly. The Center for Biological Diversity is happy to provide you with the requested information and be of service in bringing the NRA up to date on this critical issue. At the risk of being too forward, may I suggest that you deploy a small portion of the NRA’s considerable resources to hire a wildlife biologist?

In 2023, the NRA posted a blog titled, “NRA Victory in Fight Over Ammo Ban.” The unnamed author wrote, “A federal court on Friday rejected a long-fought effort by environmental groups to force a ban on lead ammo in a national forest, providing a key win for hunters, the National Rifle Association, and the United States Forest Service.”

In 1991, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service banned lead ammunition in waterfowl hunting due to concerns about waterfowl health from ingesting lead bullets. California banned all lead ammunition in hunting in 2019. For Neumann, switching away from lead ammunition was an easy decision.

“The things that I have heard people come up with for not doing it have been very similar [to] what my son would use not to mow the lawn,” she says. “I can’t find the lawn mower. I can’t find the copper slugs. I can go online and have them sent to me, you know? If I can find them, other people can find them.”

While copper slugs are slightly more expensive than lead slugs, Neumann claims they are more accurate.

“You need to have a rifle barrel on your shotgun in order to shoot these copper slugs. And so most hunters I know would go, ‘Oh, I need a new gun.’ And everyone else would go, ‘yes, you do.’ Go get a new gun so you cannot poison your family,” she tells Sentient.

When reached for comment about Hunters for the Hungry, the NRA did not respond to questions about lead ammunition or lead testing with regards to their programs. Peter Churchbourne, Managing Director of NRA Hunting, Conservation and Ranges, wrote to Sentient of their role in these programs, “The NRA has been involved with the Hunters for the Hungry initiative since the mid-1990s. We are one of the country’s largest proponents and funders of the independent organizations known as Hunters for the Hungry and/or Hunters Sharing the Harvest…Our involvement has evolved over the years, and we now foster public awareness through education, fundraising, and publicity.”

It is true that venison donation programs have likely fed hundreds of thousands of families throughout the country. In the last Iowa hunting season alone, 3,000 deer were donated, “yielding over half a million pounds of fresh venison that’s going to folks in need,” Elliott of the Iowa DNR tells Sentient.

“Placing restrictions on the type of ammunition used may significantly reduce participation and donations, ultimately limiting the program’s ability to provide much-needed venison to communities,” West Virginia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Biologist Trevor Moore wrote to Sentient. “By maintaining accessibility and encouraging best practices, we can maximize the program’s reach and continue making a meaningful impact while staying committed to education and safety.”

In Minnesota, which shares a border with the state of Iowa, venison hunted via firearm “must undergo screening for lead by x-ray prior to distribution. Any packages found to contain lead are discarded.”

Many venison donation programs tell Sentient that they test for chronic wasting disease, a neurodegenerative disease that affects deer and elk, that has not been shown to infect humans. Even states that test game meat for that disease, like Wisconsin, do not test for lead.

“I do think that it would be quite possible to move for all meat to be inspected by the Food Safety Inspection Service,” Hanson says. “The problem is in places like rural Iowa, rural Indiana, or rural Oregon, anywhere, there aren’t enough inspectors already. Someone would have to have to pay for the inspection, even if it’s meat given away.”

Missouri, Iowa, Utah and Wisconsin are among states where programs “encourage” hunters to consider using non-lead ammunition when hunting game for donation. Some states, like New York, are offering rebates for hunters who purchase non-lead ammunition.

“Trying to do this on a sort of a volunteer basis, based on the hunters, that’s not a solution,” Harper says. “There’s a great need for meat protein in food banks, but there’s a definite human health concern with venison harvested with lead ammunition.”

In 2014, Neumann and her group petitioned the Iowa Department of Natural Resources to restrict “deer donated to HUSH to be taken with nontoxic ammunition or archery equipment.” Then-commissioner and secretary of the Natural Resource Commission (a group appointed by the governor, who at the time was NRA-endorsed Terry Branstad) wrote to colleagues that he hoped the DNR could “deal with this quickly so we don’t have to listen to a bunch of pseudoscience again.” The department denied the petition, citing “no evidence linking human consumption of venison to lead poisoning.”

Within the documents Sentient obtained, one voice within the Iowa DNR was steadily disappointed by his colleagues. In internal emails, a natural resource tech wrote that one of his colleagues was “dismissive of the lead effect.” In another email, he wrote, “Many second amendment rights individuals are viewing our promotion of nontoxic ammunition as [taking]…the guns of hunters. It is not. It is to eliminate a fate worse than death, dying of lead poisoning.”

“It’s just a good conservation measure to have good rules and regulations to not poison wildlife or poison children,” Neumann says. “The reasonable thing is to try to prevent people from ingesting this, and they have tools to do that. They just won’t do it.”