News

RFK’s New Dietary Guidelines Delayed Again, Amid Concerns

Diet•6 min read

Solutions

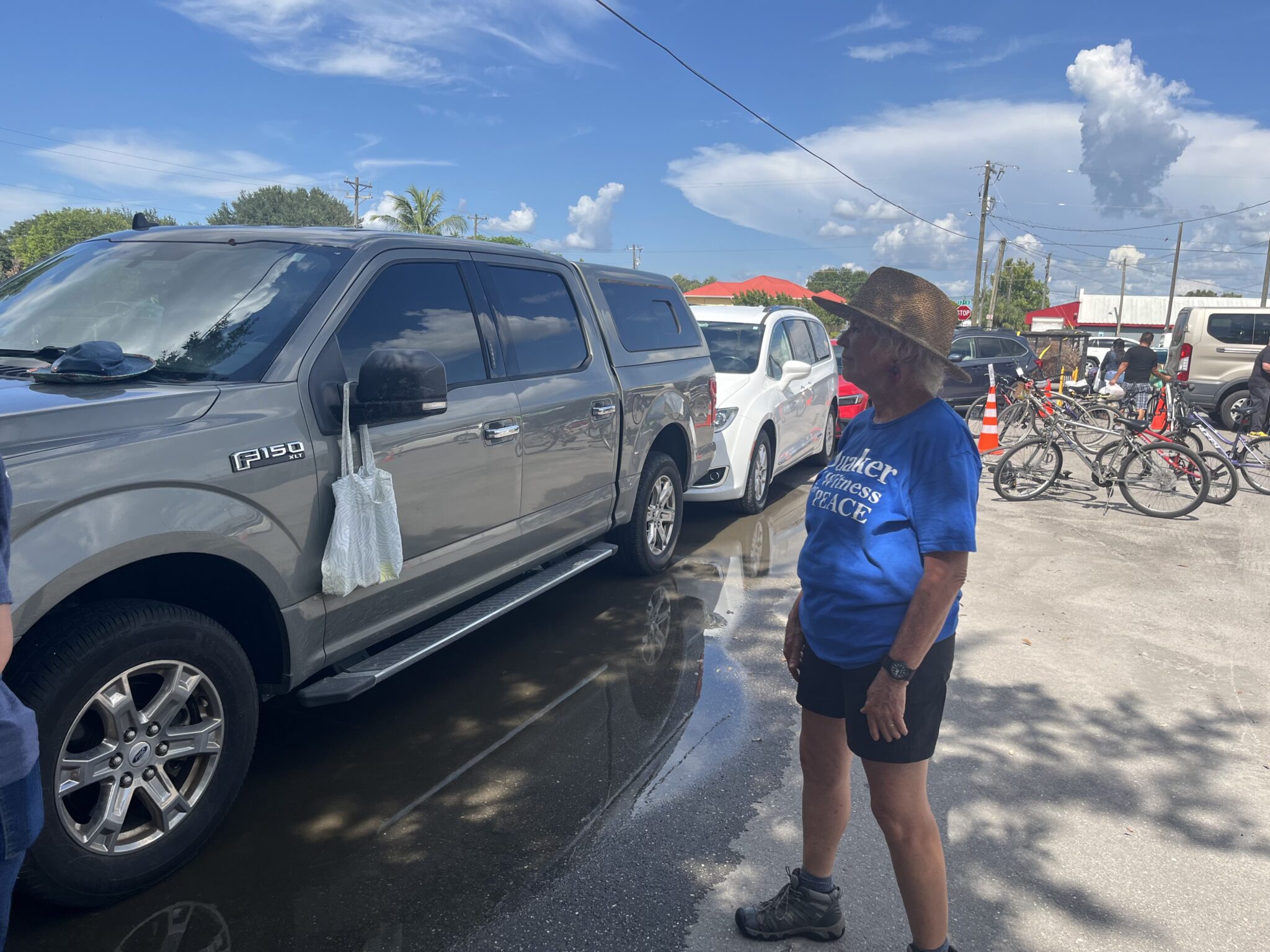

Volunteers keep an eye out for ICE while others grow and distribute plants like cactus and jute mallow.

Words by Grace Hussain

There are more than 300 farms in Collier County, Florida, perhaps best known for growing tomatoes. Yet within the county, in the unincorporated community of Immokalee, farmworkers often struggle to put fresh fruit and vegetables on their own tables. Some Immokalee farmworkers were born outside of the U.S., mostly in Guatemala, Haiti or Mexico, while others are Indigenous, working land now owned by others. Cultivate Abundance is part of a network of organizations working to address food disparities here, growing fresh produce on gardens and plots throughout the community that is distributed every Friday. The group’s aim is to boost food security and access to healthy food, but any effort to boost consumption of plants is good for the planet too.

The food system is responsible for about a third of all greenhouse gas emissions, with the lion’s share of that attributable to meat, especially beef. Eating more plants and less beef is one of the most effective forms of climate action, according to Project Drawdown, and more plants are also good for personal health. But access to healthy produce is an ongoing challenge here. The farmworker community in Immokalee is caught at the intersection of food apartheid, threat of persecution from immigration authorities and rising temperatures.

Cultivate Abundance provides bags of produce each week to around 1,000 community members, according to their website. While most of the produce comes from a partnership with a local food bank, the donations often miss the mark. On 10 acres of land spread out across Immokalee, Cultivate Abundance grows a variety of produce that is selected with intention. The group plants crops that can withstand the heat, and that are culturally appropriate for the diverse group of farmworkers they aim to nourish. The goal is to to fill the gaps left by food bank donations and the measly selection at stores in the neighborhood.

Stewarding these different spaces is a group effort, Lupita Vazquez who manages the gardens and the nonprofit’s outreach tells Sentient. “The status of our location isn’t guaranteed, just like climate change now doesn’t guarantee you anything in terms of growing,” she says. “When we share the responsibility and spread it out, then there’s an infusion of hope.”

At one of the gardens, located behind a food distribution center run by another group, Misión Peniel, Vazquez tends to plants like okra and chayote. “We mostly focus on zone tolerant plants,” Vazquez says, referencing the USDA’s plant hardiness zones, mindful of what can withstand the heat and extreme weather events made more common thanks to climate change.

What is culturally appropriate varies too. Some gardens grow corn, beans and squash, others grow cactus and “leafy greens that would be considered weeds, but are forageable,” while donations of some tropical fruits, like mango and avocado, fill in gaps too.

One food you won’t find them growing: tomatoes. “We’re not growing tomatoes because this place is inundated with tomatoes,” says Vasquez. In 2022, tomatoes were planted on over 15,000 acres of land in Collier County, Florida.

On the day that I visit, temperatures in Immokalee, Florida reach into the 90s and a heat advisory is in effect. Despite rising temperatures, last year Florida’s Governor Ron Desantis, signed a ban on municipalities passing heat protections for workers.

The queue for the distribution center is already growing, a full two hours before distribution begins. Volunteers set up an assembly line, filling plastic grocery bags with a variety of produce, enough for the 350 people they expect that day. By now, the group has learned how much they need to ensure everyone is fed without wasting food.

The group works to understand who is lining up, in order to better serve their needs. According to the group’s survey efforts, for those lining up this may be the only fresh produce they get to bring home to their families that week.

Over 40 percent of Immokalee’s residents live at or below the poverty line, according to USDA data. Rising food costs are a problem across the U.S., but prices are especially high in Immokalee.

Immokalee residents are subject to food apartheid, a term used to describe a community suffering from decades of systemic injustices related to healthy food access. Most of the people who come for the distribution are on foot, with a handful arriving on bikes. Many find it a challenge to get to the one grocery store in town, a Winn-Dixie.

The produce at the Winn-Dixie in town can be limited, Ellen Burnette, Cultivate Abundance’s Executive Director, tells Sentient. When shopping online, you can order products like key limes and potted basil plants from a store in Naples but not the store in Immokalee. Lynn Charleston, a volunteer with the nonprofit who lives in Immokalee says that she’s been told by store staff that they’re simply not sent the same products as the stores in nearby Naples and Ft. Myers.

Southeastern Grocers, Winn-Dixie’s parent company, told Sentient in a statement in response that “each Winn-Dixie store is thoughtfully curated to reflect the unique preferences and needs of its local community…The Immokalee store features a wide selection of locally and culturally relevant items, including a robust variety of produce and everyday essentials that resonate with local customers.” They also pointed out that their online ordering system “may not always display the full breadth of in-store inventory.”

The haul that day includes over a dozen different plants, among them chayamansa (Maya spinach), jute mallow (a leafy green grown in Haiti), starfruit and nopales (cactus). “These aren’t exactly inexpensive groceries,” says Juan, who prefers to use his first name only, noting that starfruit and cactus tend to be priced higher than carrots or tomatoes at the grocery store, which is why it is especially important to grow and distribute these foods.

Juan used to “be on the other side of the line,” but now prepares bags for distribution as a volunteer, alongside work with the local grassroots movement Unidos Immokalee. The jute mallow and chayamansa supplement what comes from the food bank, which isn’t always so fresh. The day I’m visiting, some of the carrots from the food bank have rotted, and Burnette says that’s not uncommon. “It’s the bags of lettuce or whatever that’s already molding, or containers of strawberry that’s got mold over the top or something,” Burnette says.

Burnette says the food bank produce tends to be “the stuff that white people eat,” rather than food that is relevant to the Immokalee farmworker community. “We wanted what we grow and collect and share to be the kind of food that the person receiving it would feel like they’re getting a taste of home,” Burnette says.

The effort to grow familiar foods is working, Vazquez says. “People come here because they get things like vegetable amaranth, Haitian Lalo, which is like a different kind of spinach, more of these things that they might remember from their own country, or that they might have more knowledge about,” Vazquez says.

As gloved volunteers sort through the bags, they take care to clean and sort the produce. This is an important part of preserving dignity for the community members they serve, Vasquez says.

Cleaning the produce also “opens up conversations” with the day’s volunteers about food banks, she says. By having those conversations, Vasquez hopes to “create some consciousness” surrounding the difference between charity and mutual aid, a term that describes helping your fellow community members.

Cultivate Abundance has had to get more creative with how they run their food distributions as immigrants and others feel the threat of ICE and other law enforcement crackdowns. During my visit, I’m asked not to take images of community members out of safety concerns. Volunteers also create a barrier of cars around the parking lot with just one entrance and exit. Several white volunteers keep their phones handy to record and engage should ICE officials show up.

“Now is the day of the old white lady,” Ellen Burnette tells Sentient of how she’s thinking of her role. “We can stand up, you know, in certain situations, we can provide like more of a barrier.” She’s not alone. Since immigration raids have increased under Trump a group of Quakers have started attending distribution, sharing water with their neighbors as they wait in line and making sure their phones are always charged and accessible.

Chris McBride is one of the Quakers who decided to volunteer after plans to construct a new detention center in the Everglades were announced. “They’re really our neighbors,” McBride tells Sentient. “We live in a farming community,” she says, adding that Independence Day was a particularly striking juxtaposition for her. “Think about the people you’re putting in the Everglades Detention Center. They pick the watermelon you are going to eat on the Fourth of July,” she says. “Now they’re in there and you’re out here enjoying your watermelon.”