Explainer

How Overconsumption Affects the Environment and Health, Explained

Climate•12 min read

Feature

Recycling is easier than going vegan, but it’s also a lot less effective.

Words by Seth Millstein

The first step to reducing your carbon footprint is knowing how to do so — but according to a new research, a lot of people don’t. A study published in the PNAS journal in June found that many people dramatically misjudge the climate impacts of various lifestyle choices, and miss out on valuable opportunities to cut down on carbon emissions as a result.

“Every choice we make has a footprint, and people often misjudge which ones are bigger and smaller,” Danielle Goldwert, one of the study’s authors, tells Sentient. “We want people to make informed choices and prioritize the biggest impacts wherever they can.”

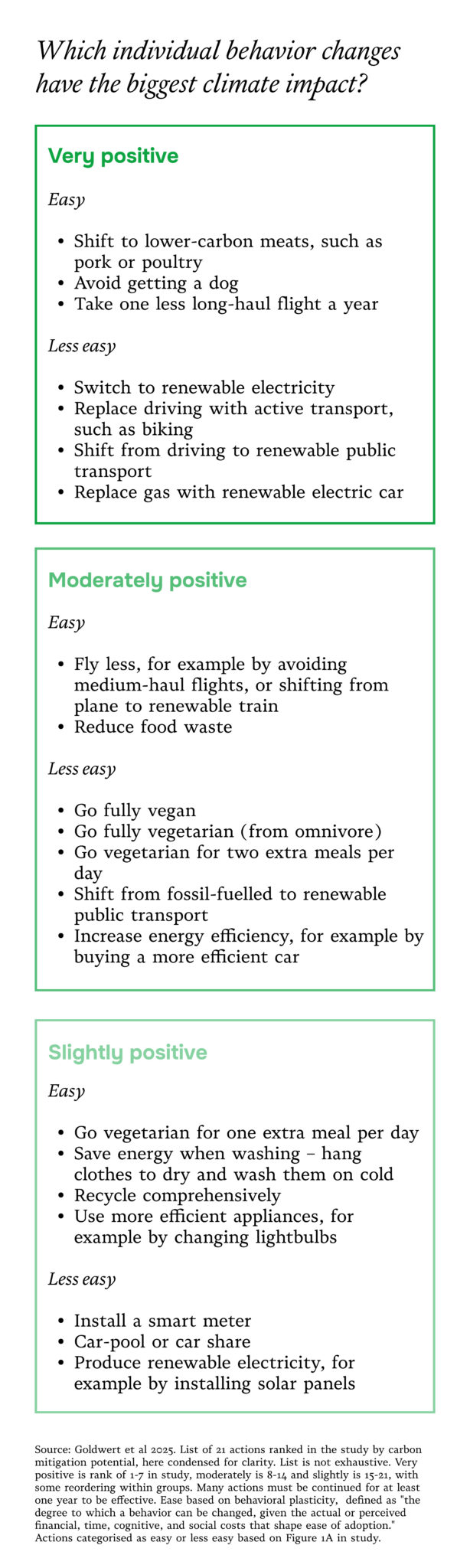

The study revealed that people routinely overestimate the climate benefits of easier behavioral changes, such as recycling and using more efficient appliances, while discounting the benefits of more difficult ones, like cutting down on long-haul flights and going vegetarian or vegan. However, once people become more informed, the researchers found, they also become willing to adopt behaviors that are more productive in fighting climate change.

So, which behaviors actually have the biggest impacts — and more importantly, how can people be convinced to adopt them? Goldwert’s study has some clues.

In the study, respondents were presented with 21 behavioral changes that can reduce one’s carbon footprint. They were next asked to rank them from most to least impactful. The researchers then revealed which ones are actually the most effective at bringing down emissions, based on a meta-analysis of existing research.

As it so happens, the respondents were largely incorrect in their beliefs about the climate impact of their behaviors.

For instance, participants overestimated the impact of recycling, using more efficient appliances, carpooling and using less electricity to wash and dry their clothes, for instance. Similarly, they underestimated the climate benefits of taking fewer transatlantic flights, getting a dog, using renewable electricity, taking public transportation and swapping out high-carbon meat like beef and lamb in favor of lower-carbon options.

Goldwert says there are a few possible explanations as to why people are so off-base in their assessments of these behaviors. One is visibility bias; we see people recycling every day, which makes it seem important and valuable, but we can’t witness people, for instance, cutting down on long-haul flights or opting to not get a dog.

Another explanation, Goldwert says, is marketing.

“For decades, campaigns have pushed recycling and light bulbs as the main climate solutions, and there’s even been some deliberate confusion on the parts of fossil fuel companies who emphasize small individual actions while downplaying the systemic level solutions which they would need to be a part of,” Goldwert says. “I think all of that shapes how people form this mental climate action map, and it contributes to why they overestimate the small things and underestimate the big ones.”

Of the 21 behavior changes that the respondents assessed, five were forms of dietary change, and the study came to some notable findings regarding them. Participants were likely to overestimate the climate impact of becoming a part-time vegetarian while underestimating the benefits of becoming fully vegetarian or vegan, and of switching to lower-carbon meats.

This isn’t to say that becoming a part-time vegetarian isn’t beneficial to the climate. All of the behaviors listed reduce carbon emissions by some amount, and a little bit of progress is always better than none at all.

Nevertheless, there is a bit of a trend here: In general, respondents overestimated the impact of dietary changes that are somewhat easier to implement, like reducing meat consumption on a part-time basis, and underestimated the impact of those that are more difficult to implement, like cutting animal products out of their diets completely.

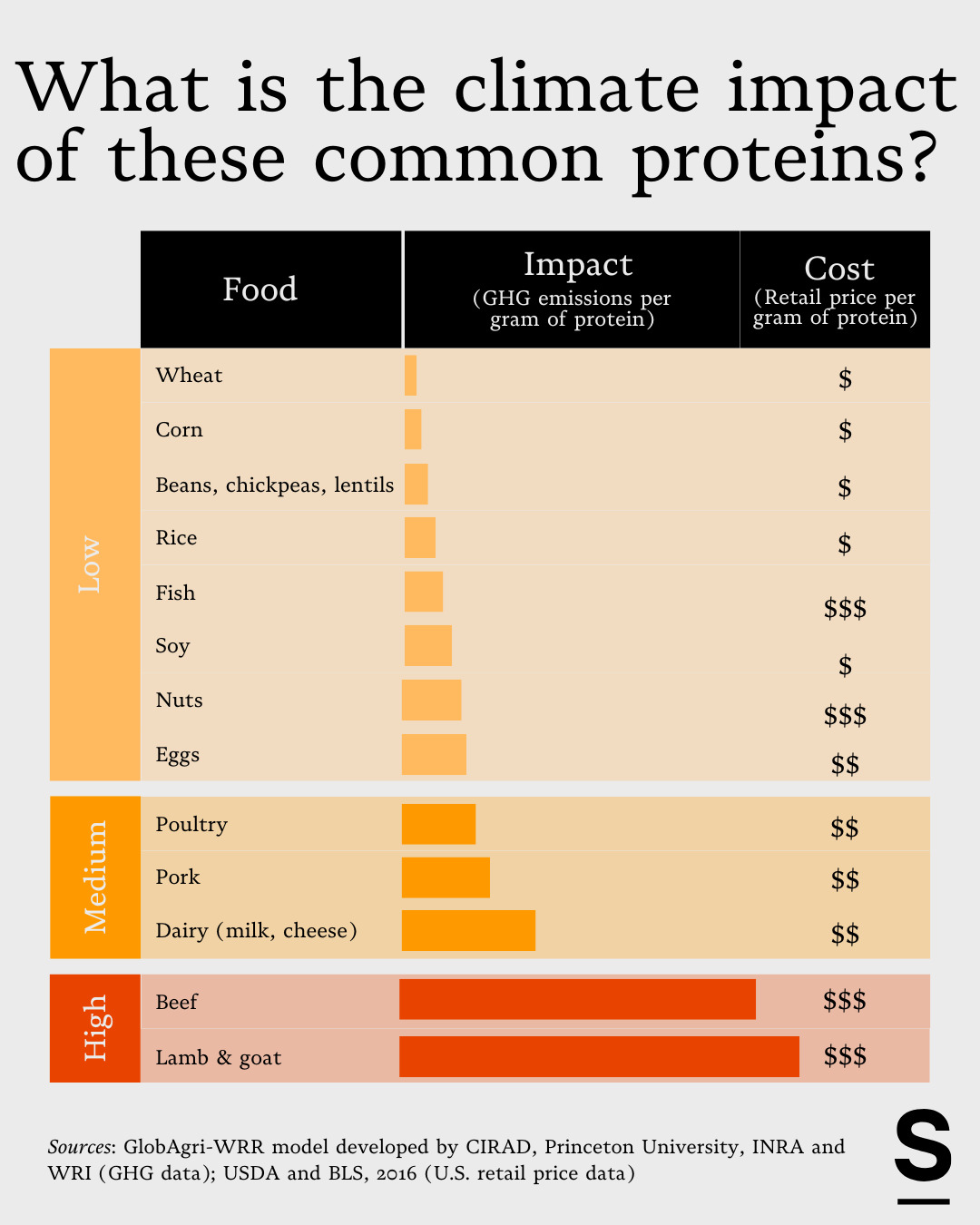

There’s one exception to this, however. It concerns the impact of shifting to lower-carbon meats, which in practice, means replacing beef, lamb and goat meat with pork, chicken or fish.

Cows, sheep and goats all produce significant amounts of methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gasses, as part of their natural digestive processes. This makes the production of those meats far more damaging to the environment — if we focus solely on emissions — than the production of pork, chicken or fish meat. If we take into account other impacts like animal welfare and clean water, the calculus of choosing between meats is far less clear.

Goldwert’s study addressed this very precisely: It looked at the impact of replacing 30 percent of the calories one gets from beef with pork- or poultry-derived calories instead. Because pork and poultry generally have fewer calories than beef, this effectively means eating slightly more meat than before — just a different kind.

One could argue that this is one of the easier dietary changes for a meat-eater to implement. And though it doesn’t address animal welfare concerns, it remains one of the more effective ways to reduce one’s climate emissions, and one that participants underestimated the impact of. As such, this specific type of dietary change may be fertile ground for anyone advocating for more climate-friendly diets.

But how can people be convinced to change their behavior in this way? The study addressed that, too.

One of the study’s more encouraging findings was that respondents expressed a willingness to act in more climate-friendly ways after the researchers told them the true impact of the various behavioral changes. But even this had some nuances to it.

In addition to assessing the climate impacts of individual-level actions, participants were also asked to rank the climate efficacy of five collective actions: Voting for pro-climate candidates, attending a climate march, cutting ties with financial institutions that invest in fossil fuels, donating to nonprofits and promoting climate action at work.

Unlike the individual-level actions, these collective actions were never assigned a “true” ranking of impact from the researchers themselves; this is because it’s effectively impossible to measure the real-world climate impact of, for instance, one additional person attending a climate march, or one person discussing climate change at work.

After informing the participants of the actual climate impacts of the various behavioral changes, the researchers then asked them how, if at all, they planned to change their own behaviors going forward. This yielded some very interesting findings that may be of use to policymakers in the future.

“We found that decisions about individual-level actions are driven more by perceived ease of adoption, while with collective-level actions, people care more about how impactful or effective those behaviors will be,” Goldwert says.

This has important implications for politicians, environmental non-profits, advocacy groups and anybody else seeking to bring about a large-scale reduction in climate emissions, as it suggests that different messaging is required depending on the type of behavior that’s being promoted.

“If you want people to change their lifestyle habits, then you need to emphasize convenience and reduce barriers,” Goldwert says; this could include making alternative proteins more affordable and tasty, and increasing access to and quality of public transportation. “But if you want people to engage civically, you should highlight the effectiveness of collective action, like how voting shifts policy, how protests change the conversation, and how system-level actions can multiply individual-level efforts.”

The researchers also identified what’s called a negative spillover effect, or “backfire” effect. When respondents were told which individual-level behavioral changes were the most effective, they generally increased their commitments to those behaviors — but they also reduced their willingness to participate in collective action to reduce climate change.

The point isn’t that everybody needs to get rid of their dog, go vegan and stop flying overseas, says Goldwert (herself the proud parent of three dogs). Rather, it’s that good intentions aren’t enough. We can’t begin to make a dent in our carbon footprint if we don’t know which of our actions are having the most impact — and as Goldwert’s study shows, we can’t rely on our intuition in deciding which actions to adopt.

“You don’t need to give up the things you love,” Goldwert says. “But you need to understand where your actions matter most, and then pair them with collective action to drive system level change.”