Investigation

‘You Feel Like You’re Marked’: Salvadoran Workers at Tyson Foods Face Risks Due to Work Permit Delays

Policy•9 min read

Feature

Sentient’s analysis finds 38 different agricultural companies were cited for noncompliance with NPDES permits, and only one was fined.

Feature • Meat Lobby • Policy

Words by Nina B. Elkadi

Deb El Food Products LLC is one of hundreds of Iowa-based companies cited for violating its National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit in 2025. Of these, 38 were food or agriculture companies. After months of dumping wastewater that exceeded the toxic compound limits set forth in the permit, the liquid egg company was cited for “significant noncompliance” by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. These types of violations pose a great threat to water quality and public health, as high concentrations of certain toxic compounds in drinking water, like nitrates, can be life-threatening to babies and may increase cancer risk in adults. Of the 38 agricultural violators identified this year, only one has been fined for its violations, in a “Sweetheart Deal” according to lawyers involved in a case against the facility.

Sentient reviewed publicly available NPDES violation letters sent by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources from January to August 2025 to identify trends in agricultural permit noncompliance. So far, in 2025, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources has issued hundreds of NPDES permit violations across various sectors. Thirty-eight different agricultural companies received 49 of these letters.

Sentient scraped NPDES violation letters from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources Document Hub and flagged discharges related to agriculture — including equipment manufacturers, chemical manufacturers and food processors. Each letter was then reviewed to confirm that it was issued in 2025.

NPDES permits were created as part of the Clean Water Act to regulate wastewater discharges from “point source” facilities, such as buildings, city water departments and manufacturing plants like Deb El Food Products. Yet under Section 402 of the Clean Water Act, farms, including factory farms that release trillions of pounds of manure each year, are not required to obtain a permit for their regular operations, unless they discharge, or propose to discharge, to public waterways.

In Iowa, fewer than 4% of CAFOs have NPDES permits, according to the EPA’s data. Discharges from CAFOs into public waterways are essentially unregulated, unless the violators are caught, in which case they typically receive a fine. Still, even regulated agricultural companies like Deb El frequently violate their wastewater discharge permits.

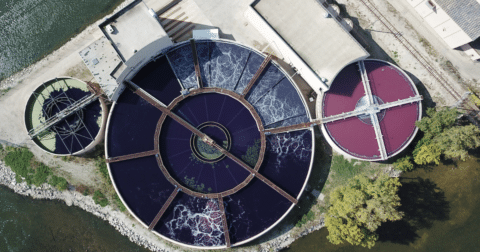

Here’s how the arrangement works. An NPDES permit serves as an agreement between the company and the water utility. The company agrees to pretreat its wastewater by filtering contaminants to levels at or below the agreed limits.

After pretreatment, the wastewater is sent to a municipal treatment plant, which finishes the treatment process of cleaning the water of its toxic pollution before releasing the water into nearby rivers or streams.

Deb El Food Products operates a facility in New Hampton, Iowa, a town with a population of 3,494. Whether the wastewater plant serves New Hampton or the Des Moines area of 600,000, the end goal is clean water. Yet even in the Iowa capital of Des Moines — which has one of the more advanced public water treatment operations in the state — the facility struggles to keep up with mounting pollution from food and agriculture production.

Many facilities in Iowa with NPDES violations have been cited repeatedly, often multiple times a year and continuing for many years.

After sending notices of violation, the Department of Natural Resources asks the polluters to report steps they “have taken, or will take,” to bring the “facility into compliance.” For Deb El Food Products, the company sent the DNR a five-step plan after it received its noncompliance notice that would enable the company to comply with the permit. These include upgrading their wastewater treatment system, increasing in-house lab testing capabilities and requesting that the city of New Hampton notify the company within 24 hours of any noncompliance.

Another violator, Daybreak Foods, updated its agreement in 2024 with the town of Eagle Grove, Iowa, to raise its permitted nitrogen and upper pH limits and planned, according to a letter to the DNR from environmental engineering firm Sigma Group, to send some of its most polluted wastewater to a lagoon system for pretreatment. Yet in 2025, the company violated again.

A fluid milk and dairy producer, DFA Dairy Brands Fluid LLC, violated its agreement with the City of Le Mars, Iowa, for three consecutive months in 2025, sending hundreds of pounds of excessive nitrogen and ammonia to a small, resource-strapped public water system for treatment.

Some polluters have violated their permits for years. Green Plains Renewable Energy describes itself as “a leading ag-tech company using innovative processes to transform annually renewable crops into sustainable, high-value ingredients.” The company was noncompliant with its NPDES permit every month, in all tested categories, from November 2024 to June 2025. This is nothing new for the company, which has violated its NPDES permit every year since 2021. Despite the ongoing nature of the violations, the state has failed to issue any fiscal penalties to Green Plains, according to the state enforcement action database.

Only one of the noncompliant agricultural facilities was penalized in 2025. Agri Star LLC received a $50,000 fine from the state for 60 total violations over multiple years. This amount is less than some one-day penalties under the Clean Water Act. Agri Star was in the midst of a legal challenge for breaching its wastewater discharge permit, but the case came to a halt with a state settlement described as a “Sweetheart Deal” by the environmental group’s lawyer in the case.

The Iowa Department of Natural Resources did not respond to an email asking how the agency determines when, or if, it intends to fine a facility. Sentient also contacted the companies mentioned in the story for comment, but did not receive a response.