Investigation

Oklahoma’s Loophole: How Tyson’s Water Use Goes Unchecked

Food•15 min read

Feature, Solutions

The two-year call to action finally persuaded the company to come to the table.

Words by Grace Hussain

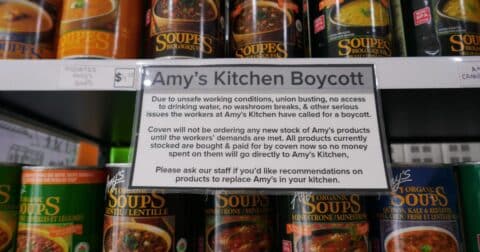

On June 12, Amy’s Kitchen workers called for an end to their two-year boycott of the company’s products. Launched with support from the vegan organization Food Empowerment Project, the boycott persisted in part thanks to support from shoppers across the country. Several grocery stores in California and Oregon even pulled Amy’s products from their shelves, according to the Food Empowerment Project.

Organizers say the boycott was a response to poor working conditions at Amy’s production facilities. “We wanted our demands and voices to be heard by Amy’s Kitchen,” Cecilia Luna Ojeda, an Amy’s employee for two decades, told Sentient in an email. “We felt this boycott was an important call to action.”

Amy’s kitchen production workers initially called for a boycott in 2022, but it was only in the last eight months that company leadership agreed to negotiate. “It took us a long time to even get a meeting, because we had to make agreements on how we’d be meeting,” says lauren Ornelas* who leads Food Empowerment Project. Part of the problem was that Amy’s leadership was hesitant to meet directly with their workers.

After months of back and forth, the non-profit, company and its employees finally sat down to a meeting — one that included translators for the workers who do not speak English and assurances that they wouldn’t lose their job for their organizing. “[The workers like Ojeda] are speaking to the people who decide if they have a job or not, and they were speaking very strongly and with great conviction about how they wanted to be treated,” says Ornelas of the meetings they had with Amy’s. “We put all our work concerns and truths on the table. They listened to our demands to improve working conditions and committed to making lasting changes for workers,” Ojeda wrote.

The months of back and forth and years of boycott eventually resulted in an informal agreement between the workers and their employer, with a promise of a pay increase and safer work conditions. Moving forward, the company will have translators available at production facilities to help staff better understand and access their benefits. Amy’s also agreed not to hire labor relations consultants moving forward, says Ornelas.

“This collaboration has facilitated productive discussions about how we can better meet our workers’ needs and enhance our communication,” said Paul Schiefer, President of Amy’s Kitchen, Inc. in a joint statement with Food Empowerment Project. “We look forward to continuing this positive dialogue and making meaningful improvements for our workforce.” Sentient reached out for additional insight, but was not provided with any additional comments.

Before agreeing to meetings, Amy’s Kitchen tried classic union-busting techniques at their San Jose, California facility — which they closed in 2022 — including firing workers who complained.

The workers who persisted, like Ojeda, continued to risk their livelihoods to fight for better working conditions, ultimately only backing down once the company agreed to certain demands. “My colleagues and I decided to end the boycott because Amy’s Kitchen has committed to improving workplace health and safety, increasing wages and respecting workers’ dignity,” Ojeda told Sentient.

If the company fails to meet these promises, Ornelas says that Food Empowerment Project is willing to support resuming the boycott, if the workers call for that step. “We don’t need anything to start campaigning again,” she points out. If the workers decide the company proves themselves to be untrustworthy, then she says she’d even back a permanent boycott of their products.

Though Ojeda and the other organizing workers were successful in coming to an agreement with their employer, some workers at Amy’s Kitchen were not on board with the activism. “At the time, the workplace was divided,” she says, but “many workers demanded improvements, and our voices needed to be heard.”

As a privately held company, it’s impossible to know how large of an impact the boycott had on Amy’s bottom line. But labor organizers can measure the engagement with the various tactics the campaign used to meet their goals.

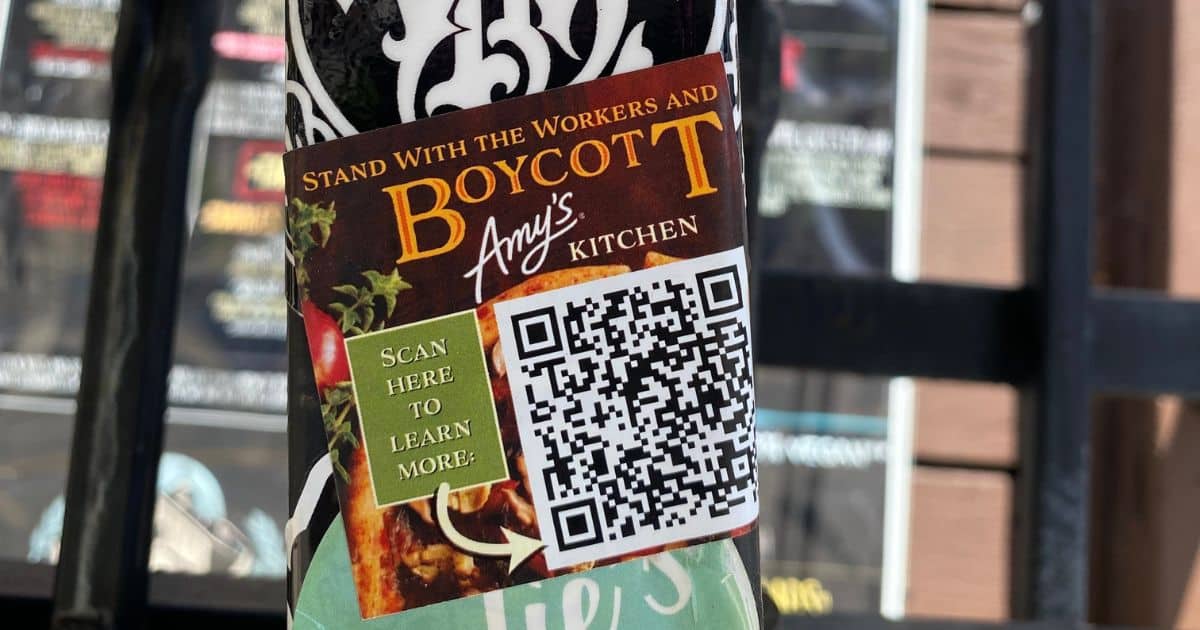

In support of the boycott, Food Empowerment Project created and distributed stickers that read “stand with the workers and boycott Amy’s Kitchen,” along with a QR code leading to the campaign webpage. The stickers, which were also available on the nonprofit’s website, were ordered more than 300 times by people in over 15 states and Canada. In total, the organization sent out more than 3,800 stickers. Food Empowerment Project encouraged recipients to stick them to water bottles or electronics but, according to Ornelas, many ended up stuck to Amy’s Kitchen products in grocery stores.

Some stores made the decision to pull Amy’s Kitchen products off their shelves completely Among them a handful of grocery co-ops, including several in California and Oregon. “We had a meeting with a whole bunch of co-ops, which the workers and I were able to speak at,” says Ornelas. “So the co-ops were able to hear from the workers themselves.”

For Ornelas, the campaign is a beautiful example of what vegans and other social justice advocates can accomplish together. “I know that for many vegans, it was hard to give up Amy’s during the boycott,” she says. Now that the boycott has come to a close, Ornelas says it’s been incredible to see vegan supporters name “what favorites they would buy again!”

Editor’s note: We spelled lauren Ornelas’s first name as she does.