News

New York Bill Aims to Ban New Mega-Dairies

Law & Justice•6 min read

Explainer

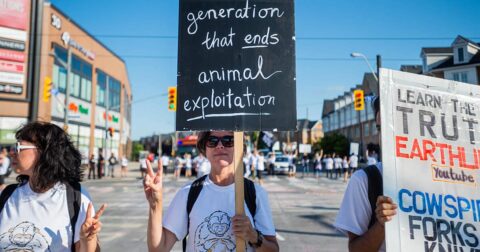

Animal rights is a revolutionary idea and social movement that requires humans to reexamine their relationship with animals, especially animals used for food.

Words by Hemi Kim

There are many awkward conversations you might have at family or work meetings as the singular vegan. It’s possible to find yourself carefully describing your food choices, aware that you are on the edge of disassembling a joyous bulgogi dish into the painful experiences that were required to produce it. Talking about issues related to animal rights can be emotionally difficult especially when eating with and cooking for others is a love language; rejecting family and friends’ cooking can be hurtful.

Yet animal advocates have managed to tap into common, shared values, successfully encouraging more and more people to reexamine what living their values really looks like, especially values of respect, empathy, imagination, cooperation, adaptability, and compassion for all living beings.

In the United States, many animals are defined as property and do not have rights in the same sense that humans have rights. At least 13 nations have symbolically acknowledged the dignity and personhood of nonhuman animals or the need to show compassion towards them as something other than objects in their constitutions. (These are Brazil, Germany, India, Switzerland, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Egypt, the Iroquois Nations, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, the People’s Republic of China, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia.) Yet such acknowledgments remain largely lip service—the animals in these thirteen nations are still treated similarly, both culturally and legally, to the animals in any other country.

Nevertheless, animal studies researchers such as Maneesha Deckha often see potential in the “shift in legal standing of nonhumans that constitutional recognition can precipitate.”

One advocacy approach seeks to translate the moral rights of animals into practical change by expanding how the law views animals: from property to personhood. Legal status as a person is something that U.S. courts have given to corporations, ships, and “entities of nature,” according to the Animal Legal Defense Fund, and it has been conferred on individual great apes outside the United States. Read more about the nuances of how advocates are trying to improve the status and legal protections of animals here.

Animal rights form part of a way of thinking about nonhuman animals as off-limits for human exploitation. People that espouse this way of thinking try to direct their own and others’ behaviors away from eating, dressing, conducting scientific experiments, and being entertained in ways that involve harm to nonhuman animals.

Animal rights is also a broad term describing animal advocacy, and the social movement focused on improving the lives of nonhuman animals. Yet the term “animal rights activist” can be alienating, which may be why groups prefer to use the terms “animal protection” or “animal advocates.”

The modern animal rights movement in the United States saw a major milestone in the 1970s with the publication of Peter Singer’s “Animal Liberation,” in which he argued that it was ethically important that nonhuman animals feel pain, and that this fact demanded far more equal treatment of nonhuman animals and humans. He also popularized the term “speciesism” to describe what happens when nonhuman animals are not given the same consideration as humans. Other thinkers, writers, and activist groups have also notably furthered and developed the fabric of the animal rights movement, both before and since Singer’s book, including Tom Regan and PETA.

Singer’s text itself reportedly sits on the shoulders of at least one British author who lived about a century prior. And for many centuries European travelers to India have learned about, and been attracted to, the concept of ahimsa and care for animals. Ahimsa, documented as early as the eighth century B.C. in Indian religious texts—Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist—affirms nonviolence and the alleviation of the suffering of all beings.

From the perspectives of scholars such as Cree writer Billy Ray Belcourt, and vegan theorists such as Aph and Syl Ko, the modern divide between animals and humans works in tandem with the imposition of white supremacy: on Indigenous people whose land was stolen by settler-colonists and who were targets of genocide, and on Black and Brown people who were and often continue to be treated as less than human.

Thus the animal protection movement in the United States is limited by the legacies and habits of thought of settler colonialism and other oppressions, and the history of the movement is whitewashed—something that people are now trying to undo. Belcourt, for example, argued in a 2020 article that people concerned with living ethically must challenge the white supremacy underpinning many efforts to expand the rights of nonhuman animals, and instead look to Indigenous traditions that see “animals as kin who co-produce a way of life that engenders care rather than and contra to suffering.”

The terms “animal welfare” and “animal rights” are similar, but animal rights is a broader idea than animal welfare. Animal welfare refers to the responsibility of humans to treat nonhuman animals well and directly care for their health, but without challenging the overall circumstances that animals find themselves in or the ways they are used in society.

For example, an animal welfare advocate may be vigilant about how animals such as bears and apes are treated in the movie industry when they are working on a set. An animal rights proponent may instead call for an end to the use of animals in films altogether.

Another example of animal welfare is when people campaign for better treatment of young chickens before they are slaughtered. Though groups that campaign for animal welfare may also support goals that are compatible with animal rights, for example when promoting the consumption of plant-based foods.

Animal rights supporters tend to be concerned that people use animals as a means to an end, typically without the animals’ assent to participate in an activity. In addition to the examples below, common areas of concern for animal rights include clothing, makeup, scientific experimentation, sports, and wildlife.

Hogs are not just the source material for a good slow roast, crispy bacon, and pork belly. The pork industry also disassembles pigs for their parts to be used as ingredients in manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, and other scientific endeavors. People who support animal rights tend to oppose all farming of livestock and fish. The fictional film “Okja” is often cited as an animal rights story dealing with these issues—one that is sympathetic to animals sent to slaughter.

Circuses, zoos, and aquariums have been the subject of animal rights campaigns and popular documentaries, such as “Blackfish”, that have resulted in changes to how the entertainment industry markets animal-based entertainment.

People concerned with animal rights might be more concerned with the potential for conscripting an animal into an unhealthy situation that exploits their labor than they would be about the benefits to humans of emotional support animals or land-mine-sniffing rats.

The arguments of critics and supporters of animal protection can seem as diverse as the number of people who express an opinion. Below are some common reasons why people may feel pulled toward or away from animal rights causes.

In “Aphro-ism”, Syl and Aph Ko promote a view of animal rights within Black Veganism that sees animal rights as essential to ending racism. They write sensitively about the topic in a way that acknowledges how white supremacy has animalized Black people. They also draw a line from the oppression of nonhuman animals to white supremacy and convincingly argue that being antiracist is essential to animal liberation.

People allied with animal rights might also include Coast Salish activists in the Block Corporate Salmon campaign, who identify themselves as Salmon People and oppose the introduction of genetically modified fish to the local wildlife environment.

People who oppose animal rights might see animals as property, and inferior to humans. They might argue that eating meat is a natural feature of the food chain, or that nonhuman animals exist for the benefit of humans.

Sometimes, deciding to disregard animal rights is a matter of practicality. For example, using life-saving products that were created with scientific research that relied on experimentation on nonhuman animals, as is the case with vaccines and pharmaceutical medicines.

As animal advocate, Christopher Soul Eubanks wrote in March 2021, “To Black people and non-vegans of all races, the animal rights movement can appear as an affluent far-left group who ignore the systemic oppression they have benefited from while using that affluence to advocate for nonhumans.” Indeed, roughly 9 out of 10 people working for farmed animal protection organizations are white. In a more racially equitable world, that number would be closer to 6 in the United States.

Colonialist harms brought about by animal rights and vegan activism can be investigated: it’s something people of the global majority and others have begun.

“Being labeled less-than-human” is a condition that most people experience, one that Black and other oppressed peoples live daily, according to Aph Ko in a chapter of “Aphro-Ism.” Ko also writes in a later chapter that “‘[a]nimal’ is a category that we shove certain bodies into when we want to justify violence against them, which is why animal liberation should concern all who are minoritized, because at any moment you can become an ‘animal’ and be considered disposable.”

For Ko, being a critical thinker is more important than believing popular, yet false, narratives about oneself and nonhuman animals. This desire to re-evaluate what one thinks is a launching point for Afrofuturist possibilities, or Black-centered creativity, a philosophical wellspring for Black veganism. You can read more about Black veganism here, here, and here.

Animal rights, then, is an opportunity to constantly ask tough questions. And asking questions creates spaces within which vulnerable communities can flourish. For antiracist humane educator Dana McPhall, the following questions guide her work:

“So what would it look like to imagine a world where I’m not defined by the racial and gender constructs imposed upon me? Where people racialized as white are no longer invested in whiteness? Where the lives of nonhuman animals are no longer circumscribed within the social construct “animal?” Where huge swaths of our planet are not considered disposable, along with the people and wildlife who inhabit them?”

Results of animal rights activism include the increasing popularity of vegan food products, a ban on selling fur in California, and state bans on using most animals in circuses. Keeping up with Sentient Media is one way to see these types of stories as they proliferate.

Nonhuman animals’ rights are not so much a question of legality or illegality, especially as laws tend to treat them as property. They are rather a way of thinking about what is morally right in a given cultural context. Avoiding the suffering of animals and respecting their right to exist are basic tenets of animal protection. As a way of thinking and being in community with others, animal rights can be an invitation for learning and imagining. Animal advocates of all races can dismantle white supremacy and undo “isms” by re-centering the experiences of Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, and other previously “less-than-human” people.