News

Ten Million Tons of Manure In California Are Unaccounted for, New Report Shows

Climate•11 min read

Analysis

A new UN-backed report is calling for the rapid transition away from intensive animal agriculture, fearing it could lead to massive biodiversity loss and the next pandemic.

Words by Caroline Christen

A recent report by the Chatham House think tank identifies the global food system as the primary driver of biodiversity loss and a risk factor for future pandemics.

The report, published on February 3 and supported by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), warns that the “global rate of species extinction is at least tens and possibly hundreds of times higher than the average rate over the past 10 million years.” Nearly one quarter of all plant and animal species are already in danger of disappearing, and another 1 million species could be extinct in the coming decades.

According to the report, the conversion of wild ecosystems into farmland was the leading cause of biodiversity loss over the past 50 years. Since 1600, the land used for agriculture has increased by around 5.5 times and continues to grow. The report attributes the increase of agricultural land in large part to the rapid expansion of animal farming.

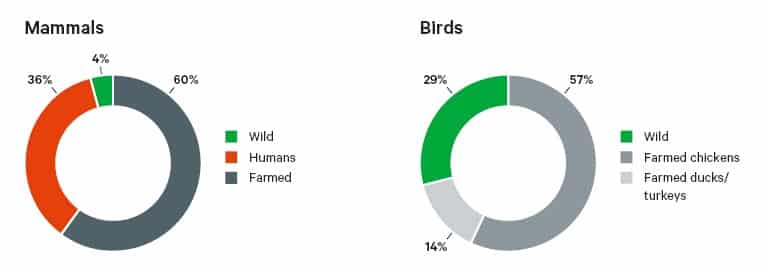

Animal agriculture currently occupies 77 percent of global agricultural land. While the biomass of wild mammals has declined by 82 percent since 1970, farmed animals now account for 60 percent of total mammal biomass, compared to humans and wild mammals, who account for 36 and 4 percent, respectively. Farmed chicken, turkeys, and ducks account for 71 percent of all bird species by mass, wild birds for 29 percent.

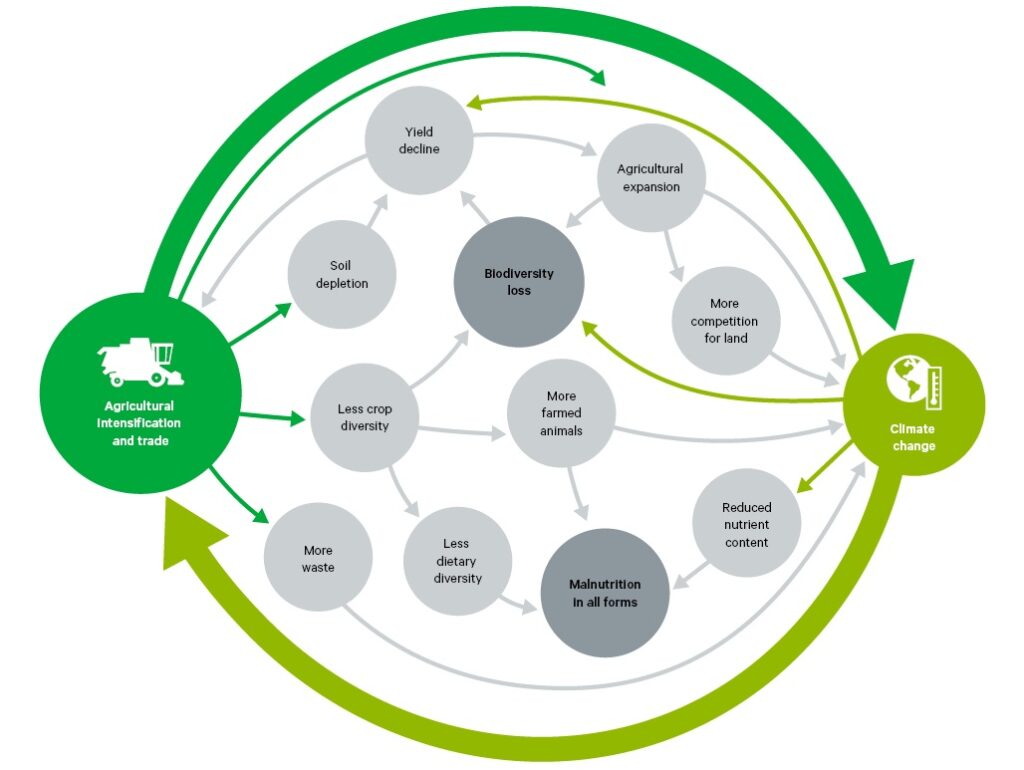

The report uses the term “cheaper food paradigm” to describe the single-minded drive for increasing productivity that has dominated the food system since World War II. According to the report, the continuous failure to consider the food system’s environmental and health impacts has created a vicious cycle that simultaneously accelerates malnutrition, biodiversity loss, and ecological breakdown.

The two main elements of this paradigm are climate change and the intensification of agriculture and agricultural trade. As climate change adds new obstacles, producers further intensify their practices, the report explains. Consequently, they convert more ecosystems into farmland, accelerate biodiversity loss, and, again, lower their output, for example, when pesticides harm important pollinators or diminish soil quality.

Intensifying agriculture is also leading to a decrease in food diversity, the report states. Intensive agriculture produces cheap calories derived from a few staple crops, while more nutritious crops are becoming more expensive.

Combined with an abundance of cheap calories, the report says that unbalanced diets can lead to an overconsumption of calories, underconsumption of nutrients, and less appreciation of food. Up to one-third of food produced for human consumption, equalling around 1.3 billion tons, is wasted every year. At the same time, about 3 billion people suffer from poor nutrition, costing the world an estimated $3.5 trillion annually.

“Driving down food prices makes it economically rational to waste and overeat food because we are surrounded by freely available calories”, says Professor Tim Benton, research director for Chatham House and lead author of the report. “We have got to get out of this mindset that we have got to grow more food. It’s about growing the right sort of foods in the right sort of way.”

Cheap crops have made it economically rational to feed grain to farmed animals instead of humans. The report also points out that increasing numbers of farmed animals displace more and more wild animals from their habitats. Over the last few decades, much of the healthy ecosystem loss has happened in the tropics, the report says, due to soy cultivation, cattle farming, and palm oil production. From 1980 to 2000, cattle ranchers converted 42 million hectares of tropical forest in Latin America into pastures.

According to the report, when wild animals lose their habitats, they come into contact with humans and farmed animals more often, increasing the risk of pandemics. The report describes novel zoonoses as “a predictable consequence of new and close contact between species caused by the expansion of agricultural land into natural ecosystems” due to an increased probability of pathogens jumping between species.

More facts and figures in the full report

To prevent the next pandemic and curb biodiversity loss, the report names three action steps:

These three action steps are interdependent because animal agriculture disproportionately impacts our access to food, water, and land. Animal products are among the most environmentally damaging foods and take up 77 percent of agricultural land while providing only 18 percent of global calories. We need to transition our diets away from such resource-intensive foods like meat and dairy to free up land and create a more biodiverse and less harmful farming system, the report explains.

If Americans switched from beef to beans, for example, they would free up 692,918 km² of agricultural land, the equivalent of 42 percent of U.S. cropland, to restore vital ecosystems or create more sustainable agriculture. The switch from beef to beans would further reduce diseases associated with red and processed meat and help the U.S. meet up to 74 percent of its 2020 greenhouse gas reduction goal, according to a 2017 study published in Climate Change.

“Demand is not a fixed quantity as a function of the number of people,” Benton says. “Demand is driven by the choices that we either make as individuals or that are forced on us by culture or food environments. We don’t need to grow ever more food to feed the world’s growing population. We need to empower people to eat healthily and sustainably, and if people make the right choices or are encouraged to have the right choices, it can make a huge difference.”

The report concludes that setting aside land exclusively to protect or restore natural habitats would provide the most benefits to biodiversity. Such a new biodiverse-friendly farming system could also be made possible by a shift towards plant-based foods. Growing plants instead of farming animals requires less land to meet the same level of human nutritional needs.