News

People Can Give Cows Tuberculosis, But We Rarely Look For It

Health•5 min read

Perspective

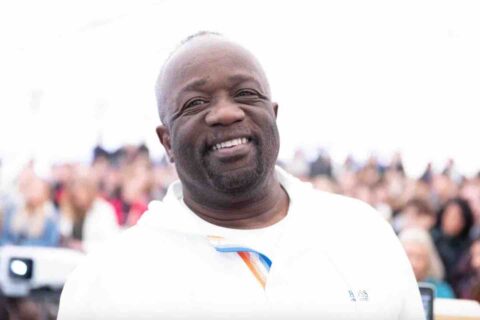

The star of the Netflix documentary, What the Health, speaks out about his experience advocating for truth and justice in all its forms. “Being a Black man in America prepared me for being vegan.”

Words by Christopher Sebastian

The first time I met Dr. Milton Mills, he was hastily eating a vegan breakfast burrito in between giving multiple lectures at Griffith College in Dublin. The burrito was cut in two, and he quickly downed the first half with a satisfied moan. Then, like your favorite auntie who is overly concerned with how thin you are, he offered the other half to me. I declined, but he wouldn’t rest until he unloaded that burrito. So he asked everyone else in the room.

Because the burrito was good, and good things were meant to be shared.

After his burrito, he rushed off to do his second lecture of the day. I caught part of it. The event was outdoors, and the main stage was under a tent. It was a packed house, and Mills was as charismatic as he always was in his lectures online.

The lecture was about veganism. He was talking about the three modes of disgust: pathogenic, moral, and sexual. As a doctor, he focuses primarily on pathogenic disgust, on how we—as humans—change the way meat looks in order to fool our subconscious brains so we won’t be disgusted by it.

That was exactly one year ago this week.

This time we were meeting on Zoom because the world had changed infinitely since the last time we met. He turned on his camera and I could see him sitting in his DC-area office wearing his scrubs.

We talked about that lecture. It’s one of the standby presentations that he does for audiences unfamiliar with the value of adopting a plant-based diet. But pathogenic disgust is not the only facet he likes to focus on, even if he is compelled to do so by default as a medical professional.

“I want to do a lecture focusing on the issue of moral disgust. Because that is just as important and just as central to who we are as human beings. And the interesting thing is that killing is so antithetical to our nature as human beings that we always have to have a reason to kill something.

“Now mind you it can be utter bullshit. But we still want that moral justification… because I know I’m violating something in my soul that says I shouldn’t do this.”

I asked him about the distinction between being vegan and being plant-based, about veganism as an ethical position and plant-based referring to a diet.

As a physician-scientist and a clinician, Mills speaks primarily about being plant-based. “I more often use plant-based because I see it as being descriptive and less political.”

That is not to say that he disagrees with the political aspects of veganism or that he doesn’t understand where people are coming from when they stake out the territory of what veganism is supposed to mean. His is a tactical decision.

“Most of the time when I’m talking to people, I’m trying to approach them from an issue of health. And I want to try and be as pure about that as I can.”

Dr. Mills posits that if people make a change based on their health, it frees them up from continuing to imbibe all the ‘BS’ rationalizations that we tell ourselves in order to justify what we do to other animals.

“That’s why I try to talk about what you should be eating because then in my mind everything else is going to come in its wake,” Mills said. “In our soul, [killing animals] is wrong. And [veganism] will also, I think, help us have better relations with one another. Marijuana may not be a gateway drug, but killing animals is a gateway to losing our moral center and throwing our moral compass off.”

That said, Dr. Mills has strong feelings about the mainstream vegan community. I asked him to describe times when he found himself at odds with his peers in the movement for animal liberation. He is not shy to talk about his experiences, but you can tell that some of them are sensitive. The alienation he felt for being outspoken for his conviction could be heard in his voice.

“Um, it can be at times very exhausting,” he said. “I think you were a part of that whole conversation I had last year? Around the Million Dollar Vegan campaign where they attempted to reach out to Trump?”

Mills was referring to an offshoot of Veganuary in which the organization designates a public figure to go vegan for a month in exchange for a million dollars to be donated toward an important cause.

The previous year’s campaign reached out to the Pope. The 2019 campaign singled out Donald Trump, asking him to eat a plant-based diet for 30 days in exchange for a million dollars donated to veterans. Mills was one of Million Dollar Vegan’s spokespeople. But he said he had no idea at the time what he was co-signing, that his likeness and his words would be used for a Trump-focused promotion.

“I came out, you know, forcefully against it. And then people started attacking me, saying why are you attacking them? And then people even tried to say, you knew that they were going to do this when you agreed to be part of their other White Coat Campaign, which I did not because there’s no effing way I would ever partner with anybody who would reach out to an open and avowed racist like Donald Trump. So there are times it gets tough.”

The difficulty of standing at the crossroads of two strongly intersecting identities that are sometimes presented as being at odds was clear—your conviction as a Black person against racism presented against your conviction about the liberation of other animals as marginalized persons themselves.

For Mills, these identities should not (and need not) exist in binary opposition. The struggles against discrimination based on race shares significant overlap with the struggle against discrimination based on species. But the mainstream community has a hard time with creating campaigns that are sensitive to the needs of both groups.

He described another situation at a conference where, in his words, people were asking him not to speak his truth.

I was at a very large conference two years ago, and I did a presentation and they told me not to be overtly political. Let’s just say I didn’t say any names. But after my lecture was over, one of the leaders of the conference came up and said, ‘You know, I really understand what you’re saying, and I agree with most of your points, but we don’t want to offend people who may be followers of this person.’

And I mean, you could see I’m still a little speechless because I [was] thinking, ‘How the hell can you ask me to give a damn about chickens in cages, about calves being ripped from their mothers, but I’m not supposed to care about human beings being ripped from their parents and put in cages and abused. What kind of morality allows you to look at this type of evil and choose not to comment on it?’

I mean do we not have some sort of moral principle that prohibits us from embracing people who are cruel and abusive? It seems to me that if you are truly what a vegan is supposed to be—and that is against cruelty and abuse and the mistreatment of the other—that covers everybody, including human beings. And if you can look at what’s happening to people of color and turn a blind eye, and come up with an excuse not to say anything or not to do anything, and you can embrace people who practice those types of behaviors, then I think you’re full of shit. And you are the worst hypocrite on Earth.

That’s when it gets tough. But I tell people all the time being a Black man in America prepared me to be vegan. Why? Because from day one, this society was telling me, you’re no good…you’re less than…you’re not smart…you don’t know what you’re doing…you need to sit down and shut up…you’re wrong.

And any person of color—especially a Black male who breaks out of that and goes on to discover who they are—has had to deal with that sort of mental assault. And […] if you have the integrity to make sure that the positions you take are founded on truth and justice, you know that what you’re doing is right.

That conviction and determination have served Mills all throughout his academic and professional career. He’s shy about revealing his age, which he laughingly calls a “carefully guarded state secret.” But his medical career has spanned more than two decades, including an appearance in the 2017 documentary What the Health.

He recounted the early days of his undergraduate years and his experiences of racism in the workplace where his perseverance was key. He said he was working full-time during the day and going to school full time at night. It was at Pacific Bell, now owned by AT&T, where Mills worked in the graphics department designing intra-company forms when he made the decision to attend medical school.

It became clear that the pre-requisite courses he needed were only available during the day so he had to quit his job. “And so I went in and I told my boss, a white woman, Bobby Maloney. I said, ‘Bobby at the end of the summer I am going to be resigning because I want to go to medical school. And I have to go to school in the daytime to get my pre-med reqs.’ She looked me up and down like she was looking at a shiftless, lazy, half-steppin’ n****r and said to me, ‘I can’t believe you’re going to quit a good job to go chasing a pipe dream.’”

Mills paused and chuckled while I looked at him in disbelief. “She most certainly did.”

I asked if he had seen her since, and he eagerly confirmed he had. “Uh-huh! Because when I got my acceptance letter from Stanford…Duke…I got five acceptance letters, I went right back to her office and spread them all on her desk, and I said you should be careful what you say to people. Because if I had less confidence in myself, if I was more insecure, I might have listened to you. And I picked up my acceptance letters and walked out of her office.”

Mills said he went back again after he graduated, but by that time she had retired.

Probably a good thing. You don’t want to be on the receiving end of Mills’ tongue when he’s on a roll.

I asked Dr. Mills if he had any words for people who are on the backfoot about veganism. Plant-based living and anti-racism have been cornerstones of his work throughout his career. And he can’t recall a time when people were collectively warm to his message. These topics are the third rail that most people avoid touching. But he grasps them both firmly with both hands, undeterred by the electric shock. He said,

I take my cue from [the book of] Isaiah. God said, “Cry aloud, spare not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their transgression, and the house of Jacob their sins.” And that’s what I try to do. In a non-condemning way, but in a forceful and direct way because I know that people oftentimes will not accept something that.

It challenges them internally the first time they hear it. But once they’ve heard it, it’s in their minds. From that point forward, it’s going to build on that foundation until eventually they can no longer deny the truth. Now that still may not mean that they are going to change their diet or lifestyle, but I can’t concern myself with people who won’t change. I’m only trying to get the ones who will.