Solutions

Eating Just 10% Less Meat Could Help Protect Drinking Water

Climate•6 min read

Reported

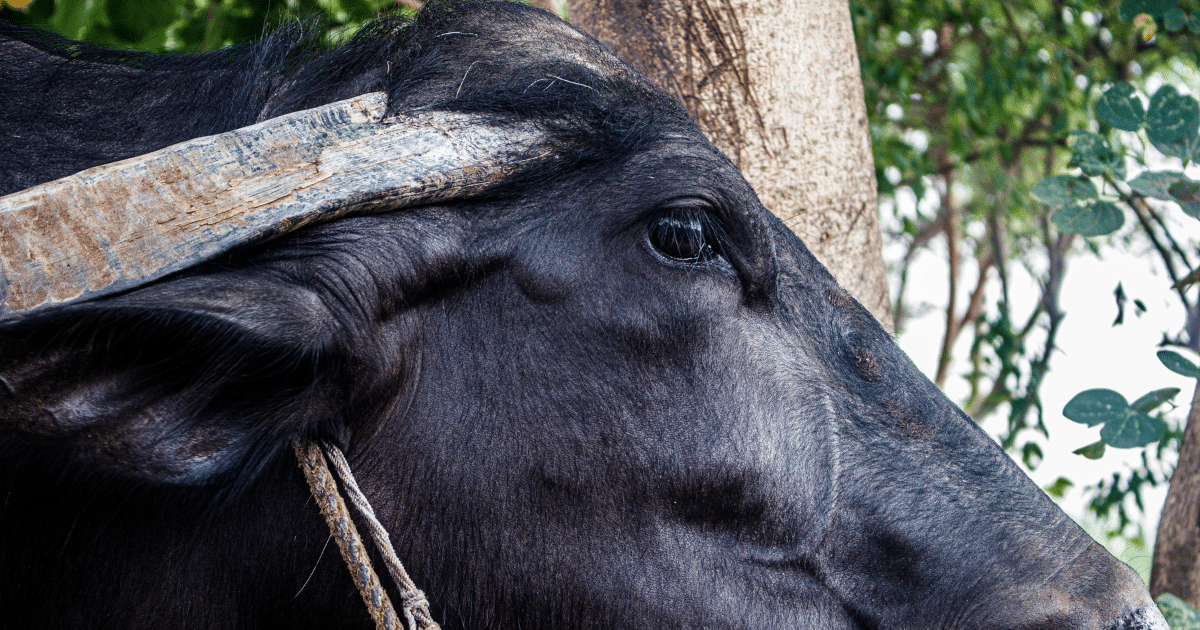

A vicious cycle of poverty, climate change, and animal suffering makes dairy farming unsustainable.

Words by Sanket Jain

In the past 40 months, four veterinary doctors visited the cattle on Babaso Punale’s farm over 40 times. “I didn’t know a single vet in our village ‘til floods devastated everything in 2019. Now, there are four vets on my speed dial list,” he says.

The 50-year-old farmer has been observing deteriorating cattle health since floods wrecked his village, Khochi, located in India’s Maharashtra state, on the western coast.

During the 2019 floods, Punale spent over four hours rescuing his Jersey cow, Mehsana, and his Murrah water buffalo from four-foot-deep, rapidly flowing floodwater. Around 6 p.m., the water level started rising, and within the next three hours, it drowned his house and the adjoining cattle shed.

Over the past decade, the region has seen increasing climate disasters like this one. After the 2021 floods, Khochi saw an intense period of dry spells, hailstorms, heat waves and incessant rainfall. Between July and October 2022, climate change events destroyed 4.5 million hectares of cropland in Maharashtra alone.

As the world gets closer to the projected threshold of 1.5-degree Celsius warming, climate disasters will likely become more intense and frequent. At the same time, the massive amounts of meat and milk that the world’s population is consuming — especially in the global north — is part of what’s driving this crisis.

Emissions from meat and dairy production make up around 14 percent of global climate pollution. India is one of the countries hardest hit by climate change events, and it has also become one of the largest dairy producers and consumers in the world — with nearly 200 million cows in 2019 and 19 percent of the global market.

In India, the consequences of climate change have been devastating — both for farmers and farm animals. Extreme heat leads to decreases in milk production and increases in calf mortality, rising rates of skin infections and infertility. Heat-stressed cows stand for longer periods of time, leading to painful conditions like lameness. On top of that, rising temperatures allow parasites to multiply faster — quickly spreading disease between animals and people.

It’s an unsustainable cycle. But for marginalized farmers looking for a way out, options are limited. Shifting to only farming sugarcane, for example, is difficult because of the higher upfront costs of production. Farmers are already seeing mounting losses because of recurring floods, hail storms and other climate change events. So while producing dairy milk may often be unprofitable, it remains many farmers’ only source of potential income, making the transition away from animal agriculture a difficult prospect.

Still, some farmers are indeed beginning to sell their cattle. Finding nutritious fodder has become difficult, and the rising medical costs and frequent vet visits have made it an economic disaster to continue owning cows. So far, only a small number of farmers have quit — but the transition has begun. Many are moving towards non-agriculture-related jobs, finding work as factory laborers. But the farmers who wish to remain farmers are stuck.

The cycle of climate change and poverty is devastating, and a closer look at individual farmers like Punale shows how it progresses.

With the help of his brother during the 2019 flood, Punale somehow walked the cattle over five kilometers to a relatively safer place. But, for the next 15 days, none of the cattle got proper feed, since Punale had lost over a thousand kilograms of green fodder to floods. “For several days, they were hungry.”

To add to the misery, “After the floodwater receded, the stench left behind made the cattle sicker.” Punale was devastated to see his cow die within two weeks. “She didn’t get proper food, and the rise in mosquitoes caused a severe infection,” he says, teary-eyed.

Moreover, two buffaloes began producing less milk — down to 9 liters from 15. Then in July 2021, before he could cope with the mounting losses of more than 120,000 kilograms of his sugarcane crop (worth 348,000 Indian Rupees or approximately $4,240) and a dwindling dairy income, another flood destroyed his village.

This time, the damage was so severe that one buffalo stopped lactating within 15 days, and the other came down to producing just four liters of milk.

Since then, “I’ve been calling a vet every 15-20 days. Earlier, the climate was good, and we would call a doctor once a year.” Punale, who’s been farming cattle for over 25 years, says he has never before seen such deteriorating cattle health, even during the catastrophic 2005 floods that affected 20 million people in Maharashtra, claiming 1000 lives.

A report by International Livestock Research Institute, Kenya finds that of the 65 animal diseases most affecting animals kept by impoverished communities, 58 percent are climate-sensitive. For Punale and millions of farmers unable to cope with such disasters, this means utter devastation of their livelihood — and for the animals — it means disease, greater suffering and death.

Another reason so many animals are getting sick? Insufficient nutrition, due to a lack of green fodder and contamination of existing fodder by pesticides banned in other countries, like chlorpyrifos.

Never in his five decades of farming did farmworker and herder Sahdev Sapkal, 67, find so little nutritious cattle feed. “I spend around six hours daily just to find the right fodder,” says Sapkal, a resident of Maharashtra’s Bhadole village.

Sometime in January 2023, he saw a fellow herder’s cow falling sick. “A private doctor said the excessive usage of pesticides contaminated the green fodder, eventually affecting the cow.”

In several parts of India, climate change is driving a rapid surge in synthetic fertilizers and pesticide usage. “Every farmer wants to harvest the crop before floods,” he explains. ”So in the hope of expecting a faster turnaround, they have doubled the use of chemicals.”

Since 1990, pesticide use has increased by over 57 percent worldwide, reaching nearly 2.7 million metric tons in 2020. Many vets in the country are now advising farmers to avoid feeding contaminated fodder to animals altogether. However, Sapkal says that it’s easier said than done.

Dr. Ravindra Deshmukh, an assistant commissioner of animal husbandry based in Maharashtra’s Jaysingpur town, says that due to inadequate nutrition, “Cattle don’t even get ten percent of the required phosphorous from the existing feed.”

The buffalo at Sapkal’s farm eats roughly 30 kilograms of fodder daily. But in the heat waves this year, the buffalo ate less than seven kilograms. Eventually, he called a vet. “The doctor diagnosed her with a heavy fever. She recovered only after administering injections and giving medicines,” he says.

In just the past nine months, the Sapkal family spent over $125 on medical fees for the pregnant buffalo. They spent an additional $200 on buying sugarcane as fodder — but it isn’t helping. As Dr. Deshmukh explains, “Sugarcane isn’t cattle fodder. They should be given para napier grass, maize feed, para grass, elephant grass and several other varieties along with proper mineral mixture.”

Yet Sapkal and thousands of other farmers in the region feed none of these to the cattle. “They just aren’t available here because a majority of the farmers only cultivate sugarcane,” explains Sapkal. With the rising floods, farmers are shifting more towards sugarcane because the crop remains safe until the floodwater enters its vascular bundle over eight feet. “So even if it floods, farmers believe there’s a hope that sugarcane can survive, but other crops won’t,” says Dr. Deshmukh.

Last year, India produced a massive 500 million metric tons of sugarcane — reflecting a transition away from from pasture. A research paper published in December 2021 in Grass and Forage Science noted that “Cultivated fodders occupy only 4 percent of the entire cultivable land in the country. Presently, the country faces a net shortfall of 35.6 percent green fodder, 10.5 percent dry crop leftovers, and 44 percent concentrate feed ingredients.”

Sapkal’s working hours are now spent finding good fodder. Ironically, he earns $3 from the cattle milk and spends over $6 on fodder daily. “Rearing cattle has become unaffordable.”

Within 15 days of flood water receding in 2021, 55-year-old tenant farmer Jaysingh Patil saw four buffaloes die. “I just couldn’t understand what happened,” said Patil, a resident of Khochi village.

At first, the cattle were seen drooling, with wetness underneath their muzzles, and lots of foam around their lips. Within a week, their diet fell severely to the point where they all stopped eating. Simultaneously, they also reported swelling and rashes on their legs. For ten days, he says, at least two doctors treated them. “Collectively, I spent over $400 on treatment.”

The infections and diseases spiraled quickly, and none survived. Even today, Patil can’t stop thinking about what went wrong. This major loss pushed his family into a deeper poverty cycle. Patil and his wife, Sunita, 50, spent ten hours on the cattle daily, mostly seeking loans, “to pay off the medical bills,” Sunital Patil explains. Even today, the loan remains unpaid, and the financial burden still weighs heavily on the family.

Patil is not alone in this. India, which has witnessed 17 floods annually for the past two decades, has reported a six percent decline in indigenous cattle numbers since the previous 2012 census. Between 2008 and 2019, India lost 849,403 cattle to climate-related disasters.

What’s more, the effects aren’t restricted to flood damage. A public vet and livestock supervisor, Raosaheb Salunkhe, from Maharashtra’s Danoli village, says, rising temperatures in the last few years have caused “a rapid increase in cases of diarrhea, heat strokes and indigestion.”

Last summer, farmer Janabai Sonawane from Bhadole village began seeing a new and unfamiliar type of skin infection on buffalo. Sonawane, who is in her mid-60s, says she’s never seen this disease before. “I consulted at least three doctors, but the red nodes keep showing every three months,” she says. Unable to afford the private vet’s fee, she started trying several indigenous medicines, but none have helped. To make matters worse, “as the temperature rises, the nodes become more prominent,” she says.

India’s understaffed public veterinary hospitals make it difficult for sick animals to receive care. India has 73,129 registered public veterinary practitioners and only 54 recognized veterinary colleges — yet a bovine population of 302.79 million.

For Sonawane, Patil, Sapkal, Punale and several others, climate change has caused more than immense financial loss. It’s as Punale says, “A loss of an important family member.”

Every rainfall now reminds him of his deceased cow, and every day, Punale spends several hours looking after his buffaloes. “I can’t lose them.”