Investigation

‘You Feel Like You’re Marked’: Salvadoran Workers at Tyson Foods Face Risks Due to Work Permit Delays

Policy•9 min read

Perspective

There is currently no entity that keeps track of emotional support animals nationwide, which is causing confusion and abuse of the system. Owners who don't need a support animal are making it harder for those that do to have one.

Words by Faith Marnecheck

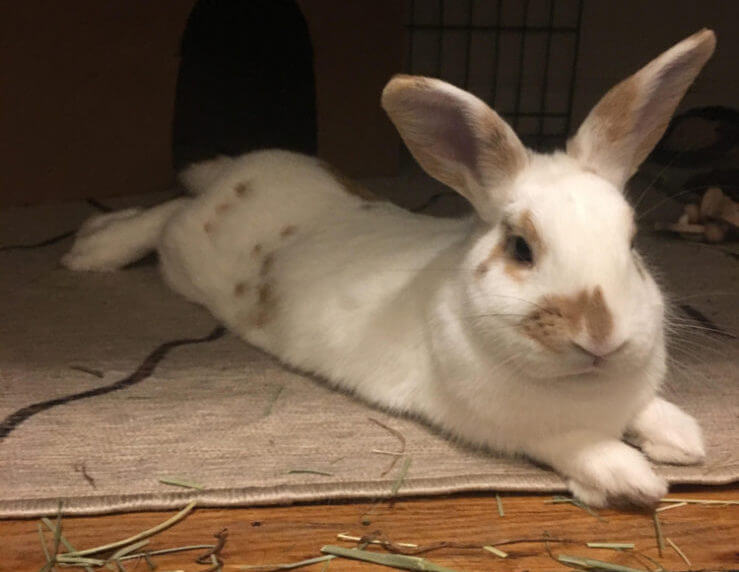

Noah DeFranceschi has hay and chewed-up cardboard under his dorm bed. When he buys items, he leaves the boxes on the floor if they do not have too much tape or ink on them. This habitat below his bed is for his emotional support animal (ESA), Chai, a brown and white bunny who loves to chew.

DeFranceschi adopted Chai in July 2018 to help with his mental health: he has been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

“If I feel like really like out of it and I don’t feel like getting out of bed, I have to push myself,” DeFranceschi said and continued, “Then I’ll get up and feed him, and then I’ll end up eating too. So it makes me feel responsible for someone else, and then I end up being more responsible for myself.”

Chai helps DeFranceschi’s depression by also making him feel less lonely and sad. When he is feeling anxious or having flashbacks that are associated with his PTSD, he pets the rabbit slowly as a way of calming himself and grounding himself in the moment. Emotional support animals, like Chai, provide an incredible service to their caretakers, and our society has a responsibility to protect these caregivers’ rights.

According to Rebecca Stone, a licensed mental health counselor in Florida who trains other professionals on how to use ESAs for treatment, the number of people with ESAs has increased significantly recently.

Along with this increase, comes attention — and abuse. On June 4, 2017, the large dog sitting next to Marlin Jackson on a Delta flight lunged at his face, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Jackson required 28 stitches and has visible scars. The dog’s owner said the Labrador mix was an emotional support dog, according to the Washington Post.

The exact number of ESAs is unknown; no entity keeps track of these animals, which has caused confusion. According to a Jan. 19 statement, Delta made its requirements for ESAs stricter because it is a “disservice to customers who have real and documented needs” to allow people to take advantage of loose regulations.

These new regulations were a long time coming. The airlines recently announced that it flew 150 percent more ESAs in 2017 than in 2015. Since 2016, Delta has had an “84 percent increase in reported animal incidents,” including urination, defecation, and biting.

This increase in incidents related to ESAs is not limited to Delta. In January 2018, a woman tried to board a United Airlines flight with a peacock she claimed was an ESA, but the airline refused because of the bird’s size, prompting the creation of a stricter policy to avoid case-by-case decisions in the future, according to the New York Times.

The lack of regulation regarding ESAs is in stark contrast to service animals. According to the Americans with Disabilities Act, a service animal is a dog who is trained to perform tasks that benefit someone with a disability, including pulling a wheelchair or pressing an elevator button. The key differences between these systems are the intense and strict training that service animals receive and the tighter regulations and requirements that leave less area for interpretation.

Stone explained that this abuse of the ESA system is in part because the system still exists in a “gray area.” She said that determining whether someone qualifies for an ESA is subjective and is decided on an individual basis according to their mental health professional’s judgment.

Although no strict set of criteria exists, Stone said that mental health professionals follow three steps in order to recommend an ESA: identify that the person has a diagnosis, confirm that “symptoms or effects of the diagnosis significantly impact the person’s daily life, and agree that the animal will alleviate at least one of these symptoms.

This “gray area” is what people take advantage of to abuse the system. Oftentimes, people try to have their pet fly for free or allow the animal to live in no-pet or pet-restricted housing, according to Stone, because these are rights afforded to ESAs by the law.

“A cottage industry sprung up in service of low-level fraud,” wrote New York Times Op-Ed Columnist David Leonhardt. “For $30 on Amazon, you can buy a bright-red dog vest that reads, EMOTIONAL SUPPORT. With a quick web search, you can find a therapist to diagnose you long-distance.”

Megan Jeter, 19, lives with her ESA Pheobe, a grey cat that Jeter adopted recently to help with her anxiety and depression. She supports stricter requirements and advocates for one central regulation system so that she and others with ESAs do not have to feel “invalidated” or have to explain themselves.

DeFranceschi,19, feels that many people assume that everyone with an ESA is exploiting the system for their own benefit because this is all that they have experienced, which “makes it so much harder to have them take you seriously.”

To protect people like DeFranceschi, it is vital that companies, universities, and governments provide accommodation to emotional support animals. With that responsibility comes the balancing act of defining limits in a world where public infrastructure was not made with animals and their caregivers in mind.