Investigation

‘You Feel Like You’re Marked’: Salvadoran Workers at Tyson Foods Face Risks Due to Work Permit Delays

Policy•9 min read

Feature

Earlier this summer, the largest meat lobby in America, the North American Meat Institute, and clean meat manufacturer Memphis Meats asked for more regulatory input from the FDA and USDA—specifically, what to call "clean" meat. On Tuesday, they settled on cell-based meat, but not much else. Food regulators from the USDA and FDA said they plan to split the responsibility of governing the cell-based meat sector between the two departments, probably because of its prospective growth. In a recent survey from animal advocates Faunalytics, 2 out of 3 people said they would try cell-based meat and more than half of them said they would replace conventional meat with "clean" meat. Almost half said they would buy it regularly. But if big meat and its consumers see a future for clean meat, then what's next from regulators?

Feature • Meat Lobby • Policy

Words by Matthew Zampa

Food regulators from the USDA and FDA said they plan to split the responsibility of governing the cell-based meat sector between the two departments, probably because of its prospective growth.

In a recent survey from animal advocates Faunalytics, 2 out of 3 people said they would try cell-based meat and more than half of them said they would replace conventional meat with “clean” meat. Almost half said they would buy it regularly.

But if big meat and its consumers see a future for clean meat, then what’s next from regulators?

Hold-ups, lots of bureaucratic hold-ups: The UK’s climate minister went as far as to say it’s not the government’s place to advice people on a climate-friendly diet, which is one of the strongest pulls for cell-based meat.

On top of shaky regulatory grounds, there’s a laundry list of other labeling problems, down to state-by-state complaints on what they classify as meat, that has not been addressed yet.

In Missouri, it is now illegal to use the word “meat” to advertise anything that does not contain flesh from a slaughtered animal. This effectively blocks the sale of Impossible Food’s 100% plant-based products statewide because they have meat on the label.

What’s worse is that a draft of the latest Dietary Recommendations for Americans said that it’s healthier to eat less red and processed meat. When others meat lobby got the word, the claim miraculously disappeared from the document.

All this confusion leads to the one logical conclusion: regulators aren’t ready for cell-based meat.

For the first time since 2012, meat is on the rise. Exports for the 35.4-billion-dollar beef industry are forecasted to increase 5% in 2018. Broiler meat, which are chickens raised specifically for consumption, is up 2%, and pork is up 1%.

The volume needed to produce this much meat is massive and can be hard to grasp. Here’s how many animals are being killed around the world, right now.

There are over 100 billion farmed animals alive today. That’s more than 10 times the number of humans. In the U.S., 99% of farmed animals live on industrial, large-scale factory farms in miserable health conditions. Earlier this summer, we spoke to Jacy Reese about the future of factory farming.

“When we combine the moral progress we’ve seen in the 20th and 21st centuries with new food technologies like clean meat,” said Reese. “It becomes clear that we can and will end animal farming. There’s simply no need for us to be producing food in such an inefficient and unethical way. I think by 2100, our descendants will look back on animal agriculture as one of the worst crimes in history.”

In Spain, there are 3.5 million more pigs than people, an increase of about 9 million pigs since 2013. Spaniards consume almost 50 pounds of pork, while the average American eats a 200-pound plate of meat every year. All this real meat consumption helps to make livestock the fourth largest generator of greenhouse gases in the world.

New trade agreements are shuffling import-export relationships around the world. That means these rankings are in flux, at least in terms of the runner-up rankings.

With China on the boilerplate, the U.S. is looking to Mexico, South America, and Japan for new trade opportunities. Plus, India and Australia just signed a free trade agreement to bolster their struggling beef markets. And Russia is increasing its pork production, mostly to meet domestic demand.

Unmitigated, the consequences of this level of demand on the climate—from animal feed production to food processing and transport—will be catastrophic.

The world’s population will demand 50% more food in the next 30 years. If that need is met by meat, the environmental stress of human food production will rise by 90%, too.

The author of this new report said by that point, the planet will not be a “safe operating space for humanity.”

Cell-based meat might be part of the solution to the consequences of meat consumption. However, manufacturers face even bigger obstacles outside the legislature. The name cell-based meat, for one, is not the most marketable.

According to the Good Food Institute, “slaughter-free meat” was the most promising in a survey of Oklahoma State University students. But is it neutral enough?

The assumption here is that “clean” meat was not. Any leanings towards advocacy could ostracize certain regulators who can’t decide whether or not “cell-based” fixes all the potential problems with the name “clean” meat.

Note: “cultured meat” performed better than “cell-based” in terms of likelihood to buy. The potential problems loom large when experts outside the legislature put cell-based meat in people terms. What works for consumers does not work for regulators.

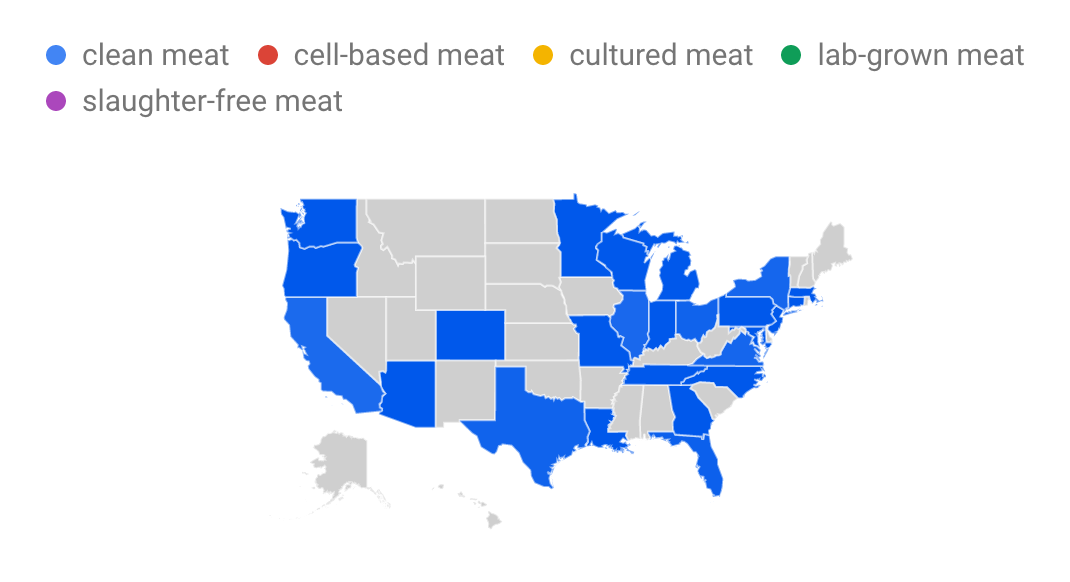

Here’s how the use of each term breaks down by region. As you can see, the industry still has some work to do.

At Tuesday’s cell-based meat summit, Kevin Kester, President of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, said he just wants a level playing field. Call beef beef and cell-based meat cell-based meat, or whatever regulators want to call it.

For now, Kester said the playing field is not level, referencing the recent pandemic over alternative milk labeling.

“Unfortunately, the FDA has consistently shown that they are unwilling, or unable, to enforce public labeling standards,” said Kester. “That agency turned a blind eye to labeling abuse for fake milk manufacturers for nearly three decades.”

That statement and the nod to “fake milk” puts him in the “almonds can’t lactate” camp. This poses yet another problem for the future of cell-based meat.

What happens when cell-based meat becomes fake meat? Kester, a beaming icon of big meat legislation, is hinting at the ability for regulators to change their minds, seemingly overnight. If the decision in Missouri provides any warning, another name change is absolutely in the cards.