Feature

Southern Right Whales Are Having Fewer Calves. Scientists Say a Warming Ocean Is to Blame.

Climate•6 min read

Reported

Beef production is a leading driver of climate emissions but in Brazil, a collaborative carbon sink project has returned a degraded cattle ranch to carbon-rich forest.

Words by Marina Martinez, Mongabay

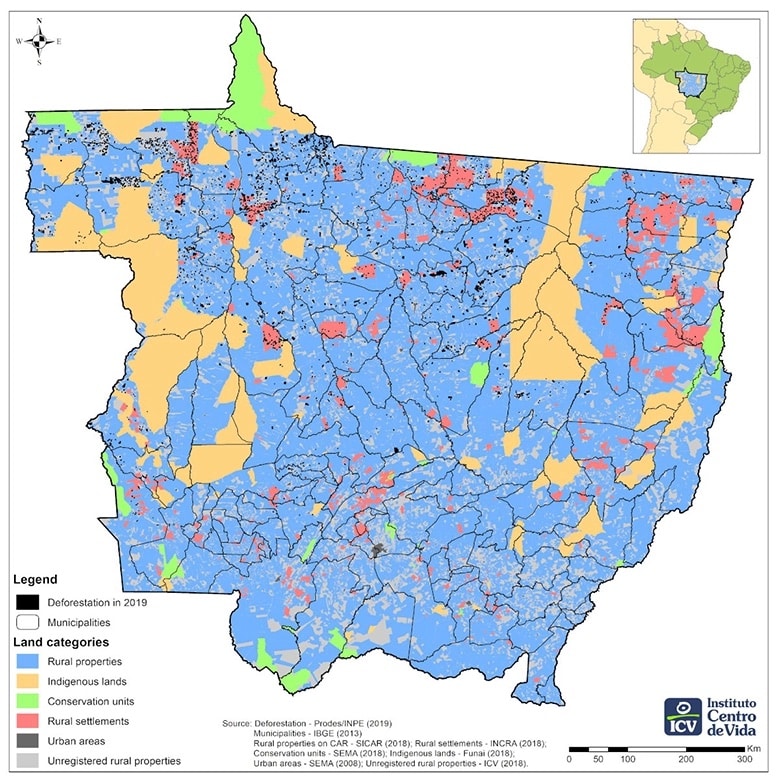

For decades, the highest deforestation rates in Brazil have been recorded at the eastern and southern edges of the Amazon rainforest. In this region, long dubbed the “arc of deforestation,” the conversion of primary rainforest into cattle pasture and soy monoculture, has been the status quo.

In 1999, a group of French and Brazilian organizations teamed up to confront that land degradation and deforestation trend. They launched an innovative reforestation and carbon sequestration project on a former cattle ranch in Cotriguaçu municipality, in Mato Grosso state, at the heart of Amazon’s arc of deforestation, introducing environmentally sound land use practices.

Despite setbacks along the way, the project is thriving today, offering its lessons learned — along with its ongoing scientific assessments and data set — as an example to others. Over the years, it has successfully strived to reforest 2,000 hectares (4,943 acres) of former cattle pasture, planting denuded soils with around 50 species of Amazon tree.

The project implementation on the ground was funded by Peugeot, the French car manufacturer, and by the French National Forest Office (ONF), a state-owned company. This 23-year-old initiative is managed today by ONF Brazil, and receives technical support from several Brazilian and international scientists from the Federal University of Mato Grosso, the National Institute for Amazonian Research, and the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development.

Initially, the Peugeot-ONF Brazil project aimed to “test the forest carbon sink concept,” a Clean Development Mechanism generated by the Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement to establish binding commitments for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gases emissions, says agro-economist and ONF Brazil manager Estelle Dugachard.

As the project matured, it became a living laboratory in which to observe the dynamics of forest restoration and carbon capture in the Amazon.

“It is an unprecedented forest restoration experiment, and we study it for that reason,” said Thiago Izzo, with the Postgraduate Program in Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation at the Federal University of Mato Grosso. Izzo is regularly joined by other university professors who teach field courses at São Nicolau Farm, where the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink Project is implemented.

Regrowing natural forests can help restore vital ecosystem services, such as clean water and healthy soils; improve biodiversity; and create quality jobs in poor rural areas — in addition to fighting climate change. The São Nicolau Farm offers real world examples of these benefits.

A recent study published in Nature found that natural forest regrowth can capture an even higher rate of carbon emissions than previously estimated by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

At São Nicolau Farm, the multi-decade effort to reforest an area the size of nearly four thousand football fields has created new habitat and an ecological corridor for wildlife endemic to the Brazilian Amazon.

“It is evident that biodiversity is returning to the area,” said Izzo, who has supervised masters and doctoral students who have collected data from the reforested area. “Several species of pollinating insects that are very important for agriculture [including native bees and wasps] are reestablishing themselves there, making nests. We have also seen a wide variety of [medium and large] mammals like monkeys, tapirs, wild pigs and jaguars passing by.”

Dozens of studies conducted by researchers from national and international institutions have been carried out at the farm over the years. One study, for example, showed that the reforestation of the 2,000-hectare fragment, boasting more than two million trees of a wide range of Amazonian species, reached a level of biodiversity much more similar to native forest than to degraded pasture in just 10 years.

But, in reforested plots where teak trees (Tectona grandis) were planted, biodiversity restoration did not go so well, said Izzo. That’s because teak trees are “allelopathic,” producing a chemical that prevents other plants from growing around them. Furthermore, teak being an exotic species, has “an unusual characteristic compared to Amazonian plants;” it loses leaves part of the year, creating a very dry environment, which is not conducive for endemic Amazon fauna nor for fire resistance, added the professor.

Dugachard, from ONF Brazil, explained the reasoning of several project partners behind the teak planting: The plan was to test whether growing and harvesting this wood could be economically advantageous, while also creating a controlled experiment for measuring the difference in carbon storage between exotic and native tree species.

Being the only exotic species introduced into the project area, the teak plots were planted separate from others and on approximately 150 hectares (618 acres), less than 10% of the total reforested area. Once harvested, new teak trees or other timber-providing species will be replanted on these plots, Dugachard said.

Combining several forest restoration techniques within the same area, with each having different associated benefits, is an effective strategy, according to Mariana Oliveira, manager of the Forest, Land Use and Agriculture Program at WRI Brazil. Assisted natural regeneration (ANR), for example, is the most used reforestation technique in the Peugeot-ONF project area. It consists of planting trees native to the local biome, with little human intervention afterward. ANR generates tremendous environmental benefits, including a large amount of carbon capture, with low maintenance costs. But the financial return on these restored lands will also be low.

On the other hand, silvicultural or agroforestry techniques, which combine the exploitation of timber or non-timber products with forest conservation, can generate significant environmental benefits, although smaller compared to ANR, but with a higher financial return.

This financial aspect is important for two reasons, says Oliveira: First, because financial sustainability is a determining factor in the success and longevity of restoration projects, and helps to provide jobs and support local rural economies. Second, meeting the growing demand for wood in domestic and foreign markets with sustainably grown and harvested trees helps ensure the preservation of primary forests.

The Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink project, as originally conceived, is planned to last at least 40 years, from 1999 to 2039. In 2011, the initiative was validated by Verra, one of the world’s most used and trusted carbon offset certifiers, and became eligible to trade carbon credits on the voluntary market. Currently, it is in its third verification phase, which will be conducted by an independent auditing entity accredited by Verra.

The project measures the carbon stock of planted trees using the methodology recommended by Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard and by the UNFCCC, says Dugachard. “We have more than 400 permanent plots, which have existed since the beginning of the project’s certification, and we measure all the trees in these permanent plots (about 40,000 in total) for biomass monitoring.”

Biomass measurement is the method most recommended by scientists for calculating carbon stock today, says Paulo Nunes, an agronomist who was responsible for estimating carbon fluxes in the project area in its initial phase. He explained that, prior to the project’s certification, the measurement was done using a carbon flux tower installed inside the farm; it measured only CO2 fluxes in the atmosphere and other climatic conditions, providing a less accurate estimate of carbon storage.

Dugachard notes that the ONF Brazil team monitors the biomass of planted trees and takes a carbon inventory annually, even though the inventory is only verified every five years by auditors. This annual assessment is done for “quality assurance,” she said. “After all, a lot changes in the forest in five years.”

A total of 394,400 metric tons of CO2 has already been sequestered by the project — the equivalent of 85,000 cars taken off the road for a year — all of which have been issued as carbon credits. According to ONF’s manager, the carbon stock significantly increased after the first 10-15 years, as planted trees reached maturity, and with the natural regeneration of vegetation.

“The amount of carbon in a restored forest increases as the succession of vegetation advances,” said Euler Nogueira, a Ph.D. in Tropical Forest Sciences from the National Institute for Amazonian Research. However, he added, carbon storage gradually decreases after the climax stage is reached. Another point of caution: If major anthropogenic or natural disturbances occur in the restored area, the young forest may begin to emit more CO2 than it sequesters. A forest fire, for example, could undo the initiative’s work overnight, releasing stored carbon into the atmosphere.

The Peugeot-ONF project’s carbon credits are being traded through Pachama, an online marketplace for credits issued by a certifying entity — Verra, in this case. Pachama assesses the integrity of carbon sink projects before they enter its portfolio. “Our team of forest scientists use remote sensing data to identify any sign of harvest or deforestation and assess a project’s additionality, emissions claims and other factors to determine the quality of the project,” the company told Mongabay.

Confirming a project’s “additionality” is critical to the environmental integrity of carbon markets. If an emissions reduction activity would not have happened without a financial incentive, then it is considered additional and eligible for the market. The Peugeot-ONF project, for example, is additional because it is using financial mechanisms to restore degraded land and turn it into a carbon sink, which would not have happened otherwise.

Pachama declined to reveal the entities that have already acquired carbon credits from the Peugeot-ONF project through its marketplace. “As a matter of policy, we do not disclose client investments in individual projects.”

The revenue obtained from the sale of carbon credits is being 100% reinvested in the maintenance of the project, says Dugachard. She told Mongabay that this revenue source is very important for the project’s survival, and was even essential during the pandemic. As COVID-19 raced through Brazil, the São Nicolau Farm had to halt its complementary economic activities, such as ecotourism.

“But the price of carbon on the international market still is not enough to fully pay for a project like ours,” the ONF Brazil manager said, “not least because our choice is to multiply our development activities and our [social] impact on the territory.”

Although the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink does not yet have a SocialCarbon certification, the project team has been working to promote positive social impacts in the rural community.

Students from local elementary schools often take field trips to São Nicolau Farm to learn about environmental issues and the reforestation project. Farmers from neighboring communities are also invited to the farm to learn about agroecology and sustainable forestry practices. According to ONF, around 10,000 people from local communities have already participated in these activities.

“These environmental education activities have had a big impact on the region. It is a rare opportunity for the local population to gain access to specialized knowledge,” says Nunes, an agronomist who has lived for years in Mato Grosso state, near São Nicolau Farm.

WRI Brazil’s Oliveira emphasizes that for restoration projects to work in the long-term, it is important that they act to “improve the quality of life in rural areas,” which goes hand-in-hand with ensuring that “the local population is being involved and heard.”

A settlement of landless farmers, whose incomes depend on the agreements they make with landowners, is located right next to São Nicolau Farm. In an innovative move, ONF Brazil has established a cooperation agreement with these farmers, allowing them to harvest Brazil nuts on the farm to supplement their incomes. In return, these workers help with land maintenance tasks and fire surveillance, Dugachard said.

“First, we mapped the Brazil nut trees inside the farm, involving farmers from the neighboring settlement in this process. Then, they created an association of Brazil nut gatherers, and now they are the ones who manage these nut trees on the farm,” said Nunes, who currently coordinates a network that supports small-scale Brazil nut gatherers in the region called Sentinels of the Forest.

Even though the Peugeot-ONF Forest Carbon Sink at São Nicolau Farm is clearly achieving successful results, the project is not without risk.

Recent years have seen an increase in environmental crimes in northwestern Mato Grosso state where the farm is located, with the invasion of local properties by timber thieves and illegal miners becoming more common, said Nunes.

The rise in crime has been facilitated by drastic reduction in funding to Brazil’s environmental enforcement agencies, first under President Michel Temer, then with even more dire cuts under President Jair Bolsonaro. Last year’s budget to those agencies was the lowest in 17 years.

State environmental protections have also declined. In the last five years, Mato Grosso authorities guaranteed impunity to two out of five environmental offenders, including in cases of serious infractions, a recent study showed. This year alone, 1 million hectares of Amazon rainforest have already been devastated by illegal fires in Mato Grosso state.

“Our collaboration with local actors protects us,” Dugachard said, when asked about the risks posed to the farm by the rising wave of environmental crime in the region. “But these are lands where the public power itself has difficulty with command and control, so it’s challenging.”

Izzo mentioned another major potential threat: Plans are underway to install a large hydroelectric dam on the Juruena River. If approved and built, its reservoir will likely flood both Indigenous lands and productive areas on the banks of the river — including parts of the São Nicolau Farm.

These threats point up a problem inherent in all carbon storage projects: While they can sequester a great deal of carbon over time, that stored carbon can return to the atmosphere due to environmental disruptions caused, for example, by sociopolitical upheaval.

Then there is the problem of scale. If these initiatives are to capture truly significant amounts of humanity’s CO2 emissions, reducing the existential threat posed by climate change, then they will need to be massively scaled up — and quickly. The hope is that the lessons offered by the Peugeot-ONF Brazil project can be applied across the country and the planet.