Investigation

What Does a Small Town Do When the Water Is Undrinkable?

Climate•8 min read

Feature

Students do learn about methane, but not about eating less meat.

Words by Gabriella Sotelo

In order to reduce climate pollution, we have to talk about food. Food production accounts for roughly a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and meat, particularly beef, is the biggest contributor to that share. Cattle produce vast amounts of methane, and raising them demands enormous quantities of land, water and feed. Yet as the scientific consensus around beef’s environmental impact has evolved, so too has the meat industry’s strategy for how we think about solutions. One fruitful approach has been to craft an educational curriculum that defines “sustainability” with no mention of what scientists say we have to do to mitigate these food-related emissions — eat less meat.

Through the federally mandated Beef Checkoff program, industry groups like the Cattlemen’s Beef Board and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) have long shaped public perception of beef. You might remember splashy ad campaigns like Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner, for instance.

This isn’t a new playbook. Documents from the NCBA acknowledged the climate impacts of beef as early as 1989 but worked to shift public attention. One strategy focused on shaping public opinion by targeting “influencers” — educators and the media, at that time.

“This sort of childhood intervention is not new,” Jennifer Jacquet, professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami, tells Sentient. “I see evidence that the meat industry has been intervening in childhood education since the 1990s around the issue of climate change.”

The industry has continued its outreach efforts, more recently aimed at reaching younger and more impressionable audiences, with a beef curriculum curated for classrooms, beginning as young as kindergarten and extending through high school.

“That this industry — notorious for environmental harms and adverse health issues — has set its sights on children doesn’t bode well for our educational systems,” Jennifer Molidor, senior food campaigner at the Center for Biological Diversity, writes to Sentient.

At first blush, its purpose sounds like a worthy one. According to a recent memo submitted by the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (AFBFA), one of the central goals of this educational program is to provide 1.65 million educators across the country with “materials that teach science through the lens of beef production.” That lens, however, is far from neutral.

The proposal sought over a half million dollars in Beef Checkoff funds, with an eye towards reaching as many students as possible out of the “nearly 3.4 million students” who received a high school diploma in 2024.

To carry out this work, the Foundation has, in addition to creating a training series for teachers, partnered with the Food and Agriculture Center for Science Education — a collaboration meant to “ensure that accurate and engaging educational materials reach classrooms nationwide.”

What counts as “accurate” in this case is, of course, largely defined by the industry itself. While the materials may meet formal education standards, they often frame beef production as environmentally sound and nutritionally essential — claims that conflict with leading public health and climate research.

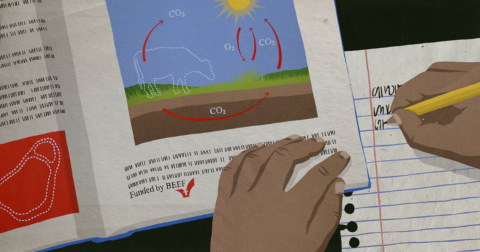

For high school students, one activity focuses on methane emissions from cattle. So far, so good, as beef production does produce climate pollution. Students are asked to analyze the “inputs and outputs” associated with raising cattle and to “articulate and evaluate solutions to the methane gas emissions issue based upon obtained knowledge.”

The materials make no mention of a critical solution, however — cutting back on how much beef we eat. Eating less meat, and more plants, is one of the most effective forms of household climate action, according to Project Drawdown. A range of experts who study the issue have said the world will not be able to make its climate goals, or at least avoid the worst global warming scenarios, without cutting back on meat.

The industry’s educational materials state the opposite of this research, and they also frame it in a way that sets up a familiar straw man. “It is not possible to eliminate methane production from ruminants, short of eliminating the rumen,” one passage reads.

Note the emphasis on elimination, rather than reduction, framing the notion of dietary change as veganizing the food system essentially rather than what famed food writer Michael Pollan has described, simply, as eating “mostly plants.”

The “elimination” mentioned in the beef industry’s materials is described as “undesirable” because it would make much of Earth’s land “unusable” for growing food. The rationale is that without cattle, there would be no manure to fertilize the soil.

In reality, meat production isn’t going anywhere any time soon. The meat industry is a 227.9 billion dollar business in the United States, and there has been no serious policy effort to reduce meat consumption, let alone eliminate it.

If the U.S. were to cut back on meat consumption — which is a critical component of climate models that include food — there will still be enough manure to fertilize cropland. After all, animal farming in the U.S is responsible for 940 billion pounds of manure and other animal waste each year. We produce too much in the U.S. — which is why nearby communities have runoff, spills and documented health impacts.

In this industry curriculum, students are also guided toward solutions that preserve the status quo — like breeding more efficient cows, tweaking feed additives or relying on carbon offsets (though many offsets are flawed or fraudulent).

“They get so close to “getting it” when they say the only solution is eliminating the source of the problem, which in a sensible world means fewer cows. With every effort to promote sustainable food, less cattle production should be part of the equation,” Molidor writes.

The materials are embedded across grade levels. In elementary school, students are introduced to cattle grazing systems. Middle schoolers examine the carbon footprint of beef, but the emphasis isn’t on how much of a massive emissions outlier beef is as compared to other foods — it’s on how improved genetics can reduce those emissions per pound of meat.

“The main concern I have is the way that they have positioned these technological advances that have to do largely with where the feed is coming from…dietary feed additives, how they position that relative to dietary choice,” says Jacquet. “The idea of meat reduction, especially beef reduction, is off the table, from their point of view, as an intervention.”

In high school, students are tasked with comparing rotational versus continuous grazing systems, often framed as a key strategy for sustainable beef production. While these industry interventions could all have some modest impact in drawing down emissions — none in terms of how animals and meatpacking workers are treated — climate scientists have made clear that it is simply not possible to abate food-related emissions without talking about the amount of beef we consume in the U.S.

Genetic improvements to reduce a cow’s carbon footprint may reduce emissions per animal to some degree, but on their own are not enough to curb beef’s climate impact.

“It is important to note that the alleged carbon sequestration posed by cattle herds in limited circumstances is temporary, not scalable, limited by location, easily disturbed, poorly measured, and does not cancel out the tradeoff that comes with it, which is increased methane emissions,” Molidor writes.

There are several goals of the program, according to the memo. One is to shape not just how students learn, but how they eat. “Students equipped with accurate information can make informed dietary choices as future consumers,” the document reads.

Another is to “play a vital role in earning trust and ensuring a positive future for U.S. beef production,” according to the same document.

Fostering trust in the meat and dairy industries became increasingly important to the meat industry after a decade or so of factory farm investigations, legal challenges and statewide reforms. One 2023 pork industry investment in higher level education also aimed to study ways to boost trust in consumers on animal welfare issues, for instance.

These materials are freely available to educators across the country, and while there’s no central tracking of where they’re used, they’re more likely to appear in states with strong agricultural ties. Programs like Oklahoma’s Ag in the Classroom partner directly with the beef industry, while the Kansas Beef Council offers a “sustainability reader series” to schools. Unlike textbooks, industry-sponsored materials can enter classrooms quietly — often through teacher training or mailings — without much oversight or review.

Jacquet, who is one of the researchers who has analyzed the NCBA’s archival documents, says the agenda here is clear: “They are certainly shaping the sort of popular discourse around what you can do to address your environmental concerns for children.”