Investigation

What Does a Small Town Do When the Water Is Undrinkable?

Climate•8 min read

Perspective

Follow along as climate researchers debunk another industry-backed study bragging about the perceived benefits of regenerative agriculture.

Words by Nicholas Carter

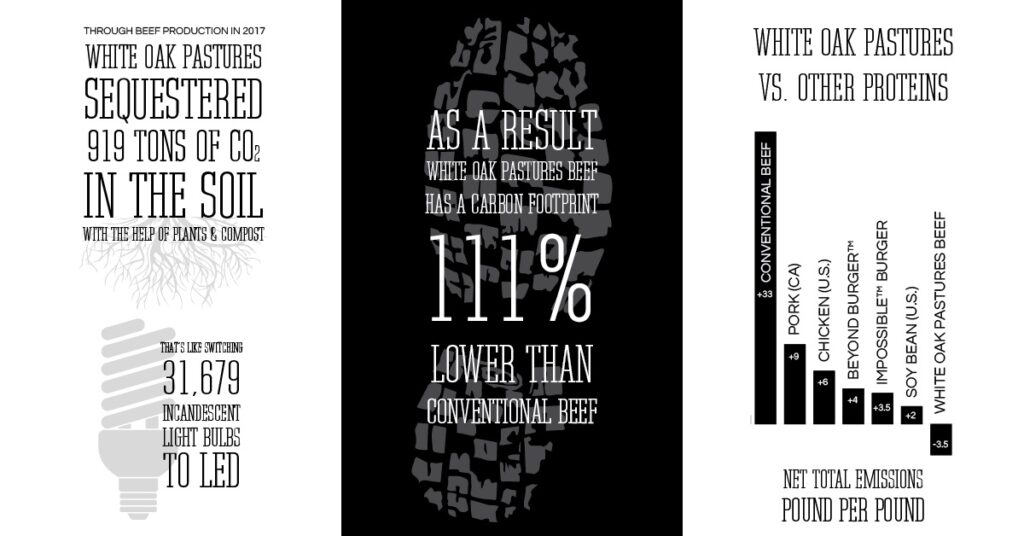

In June 2019, we reviewed a study by the environmental consultancy Quantis that was commissioned by White Oak Pastures (WOP). Quantis concluded that WOP was storing more carbon in its soil than the combined greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of its pasture-raised cows during their lifetime. Our brief review was critical, partly due to the clear bias in a previous Nestle-funded Quantis study which concluded that allowing plastic bottles in national parks was ecologically benign. However, the main criticism was because of the large body of scientific literature refuting the claims of so-called “regenerative grazing,” an idea popularized by Allan Savory, and which also goes under names such as “holistic grazing” and “rotational grazing.” Subsequently, WOP began to make wide-scale claims about their carbon-negative beef.

In late 2020, a peer-reviewed life cycle assessment was published by Rowntree et. al (2020): Ecosystem Impacts and Productive Capacity of a Multi-Species Pastured Livestock System. In this study, mixed farming of cattle, pigs, and poultry birds (mainly chickens) was compared to the conventional farming of each species.

Off the top, we note that WOP does use well-known methods that show potential improvements over standard North American grazing practices. They apply compost to their land, use legume cover crops to make nitrogen available, and also include local forbs, clovers, and nut-bearing trees. Chemical fertilizers and herbicides are not used. Such methods, amongst others, have long been used in Conservation Agriculture, and are also applied to farming plant-based foods.

WOP also prevents overgrazing by having limits on the number of animals per unit area, i.e. “stocking density,” and rotating animals to prevent overgrazing in any one particular area.

Soil organic carbon measurements

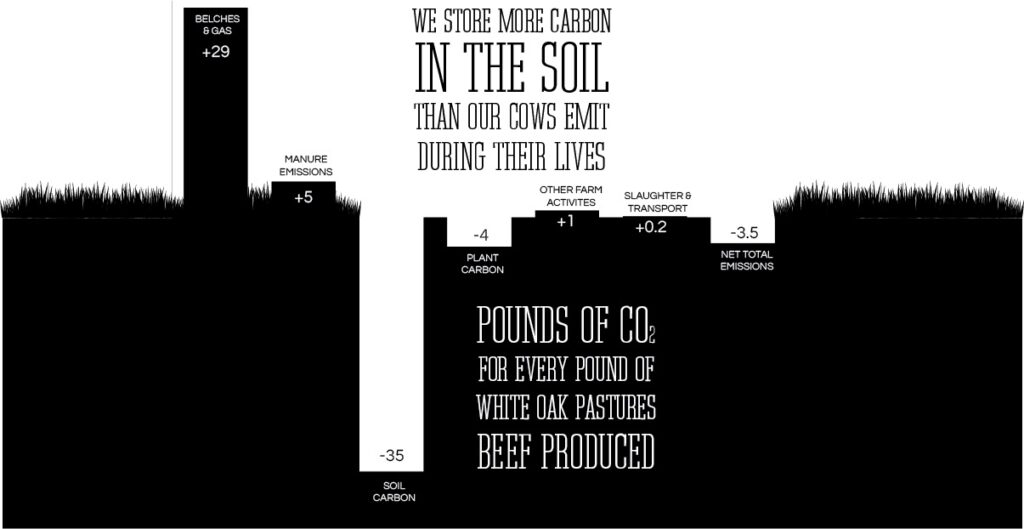

Evidently, the paper is making a special attempt to promote the idea that grazing cattle may be carbon negative. Below we will highlight why this suggestion is a skewed and exaggerated interpretation of the available evidence regarding the subject of optimized grazing and human-managed grasslands.

Inputs from off-farm sources

Inputs that arose from off-farm sources were not properly accounted for. The study is presented as if the intrinsic qualities of the farm, especially the grazing methods, were responsible for the main SOC sequestration. However, the paper does note that large quantities of hay from off-farmed sources were added as feed and fertilizer during the initial land management and ceased thereafter. This was about 10,000 pounds per acre, for 200 acres according to the data. Resulting cattle manure and hay decomposition act as fertilizer. It is difficult to interpret whether this applied to a single 200 acre area, or if other 200 acres sections received the same treatment in stages.

More importantly, WOP monogastric animals, mainly chickens and pigs, consumed feed crops that were imported from off-farm sources, year after year. According to the supplementary data, the feed quantity was 1.8 million kg (4.034 million pounds) in a sample year. In addition, there was 11793 kg (26000 lbs) of mineral bar per year. See tab 1 of the supplementary data for details.

Considering that the combined carcass weight of chickens and pigs exceeded that of slaughtered cattle on the farm, this manure from the off-farm feed is a substantial fertilizer derived from external food sources. Manure from all animals, including these monogastric animals, was used to fertilize the WOP land. This is important since fertilizing soil contributes to vegetation growth, which is the main cause of increased SOC. On its own, this critical missing factor in the paper’s calculations could account for the majority increase in SOC, completely skewing the results, and invalidating their conclusions about “regenerative grazing.” Such lapses are signature characteristics of industry affiliated “research.”

Creative accounting of land use by WOP animals

Further accounting misdemeanors were found through examining the paper and supplementary data. Firstly, note that the land used to grow the monogastric feed discussed in the prior section was not accounted for. WOP consists of 3000 acres, equal to 1214 hectares. However, most or all of the monogastric animal feed was from off farmed sources; this land was not accounted for.

Hence, the calculation of monogastric animal feed should include the land used for their feed production. The promoters of regenerative grazing heavily criticize “row cropping” and monoculture, yet there is no indication that the feed for these animals (roughly 1.8 million kg per year in the year used in their data) was from any form of conservation agriculture. It is possible that chemical fertilizers and pesticides were used, ultimately benefiting the WOP farmland.

However, there is a much larger accounting misdemeanor. The study averages the proportionate share of land according to the net carcass weight of each animal species, as well as egg mass. As such, poultry birds, which made up 43.2 percent of the carcass weight, were attributed about 43.2 percent of the use of WOP land. Pigs were attributed about 10.2 percent, and eggs about 3.5 percent according to their relative mass. Cattle, sheep, and goats were attributed 42.1 percent, 0.82 percent, and 0.15 percent respectively. But note that the cattle, sheep, and goats mainly consumed plant matter derived from WOP pasture land, while monogastric animals were fed using imported foods. Despite this discrepancy, the study averages the land use amongst all the animals. This is accounting that attributes a much smaller amount of land to the ruminants, mainly cattle, while the monogastric animals are used to dilute their impact through creative accounting, masking the true impact of the cattle.

In reality, the majority of WOP land should be allotted as part of the cattle land footprint, thus up to 2.4x the land they are currently allotted. Currently, this paper implies that cattle utilize 2.5 times the land of conventional cattle, the same factor of 2.5x averaged with the other animals. However, cattle should be considered as using 5-6x the land of conventional cattle meat, while the pigs and poultry birds are allotted the off-farm land actually used to grow their feed.

Again, this drastically alters the conclusions we should draw about “regenerative” grazing, and how we understand the implications and patterns of industry-funded studies. There may well be other such liberties taken with data collection, handling, and calculations, but our team does not have unlimited time or access to material data from WOP to analyze further. We hope that the largest lapses are thus detected and encourage others to analyze for themselves. The disturbing problem is that few people have ample time to analyze every study, especially those conducted by the hand of industry.

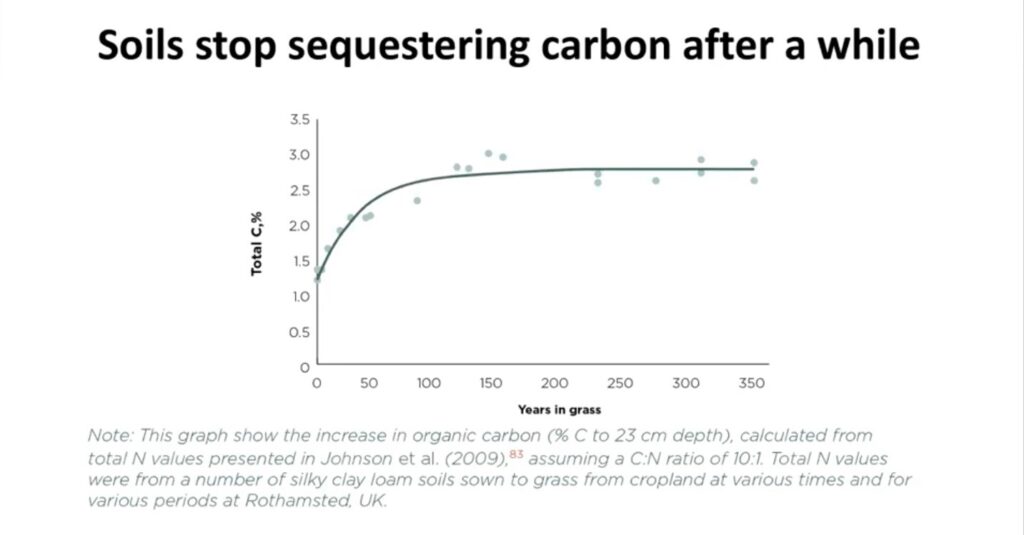

Land characteristics of WOP and SOC sequestration potential

WOP is a land area with excellent water and temperature conditions but was severely depleted from prior extractive farming techniques for corn, peanut, soybeans, and wheat. As such, initial years of either improved plant or animal farming should sequester SOC, noting that the yearly amounts are known to slow and plateau over time. SOC sequestration is a good strategy in areas such as WOP, but note that it has a limit. Net increased soil carbon sequestration would be less on land that was initially in better condition, closer to its peak carbon level.

This point is important since “regenerative grazing” advocates usually imply SOC sequestration can be used as an unlimited strategy, which is not possible.

Total land carbon storage vs soil organic carbon (SOC)

The paper continues to focus on the misleading paradigm of using soil organic carbon, rather than total land carbon storage, which is the proper measure to use.

Total Carbon stored on a landmass = [Above Ground Vegetation (i.e. plants and entire trees)] + [Above Ground Detritus (logs, leaves, and all other organic matter)] + [Soil Organic Carbon (as measured in this study)] + [Soil Inorganic Carbon] + [Below Ground Detritus and Live Matter (i.e. carbon in the roots of trees and all other plants)]

Optimized grazing certainly stores more SOC than poor grazing or cropping practices. However, optimized plant agriculture also increases SOC, and produces more protein and calories per unit of land. Both of these practices, however, store far less total land carbon compared to rewilding and reforestation. Note that monogastric animals (i.e. chickens and pigs) also use less land than ruminants (i.e. cattle, sheep, and goats) and would allow some saved land for rewilding, but not as much as plant foods for direct human consumption. In such cases, livestock is thought to have a lower impact when diversified and integrated with crop cultivation, although the net benefit is largely due to lower numbers of animals per unit land rather than more intensive grazing practices. Furthermore, grain-fed cattle use less land and feed than grazed cattle, though still more than monogastric animals, to create the same amount of food. Therefore, the change in land use must be quantified when calculating the carbon impact of any product, especially ruminant/cattle meat.

According to Lal (2010), all undisturbed natural ecosystems contain more soil organic carbon than their agricultural counterparts that, on average, sequester 25–75 percent less. Such natural ecosystems include forests, wetlands, and grasslands. All pasture or cropland was originally a type of natural ecosystem that has been converted to human use.

As such, Rowntree et. al (2020) did not measure the carbon opportunity cost of land, which more comprehensive studies do include in LCAs. To understand the magnitude of this opportunity, it was shown that shifts in global food production to plant-based diets by 2050 could lead to sequestration of 332–547 GtCO2, equivalent to 99–163 percent of the CO2 emissions budget, 19 years of total fossil fuel emissions of upper and middle-income countries. This is very significant during our current climate crisis.

This is accomplished by replacing animal-based foods with optimal plant protein foods, grown on a much smaller fraction of land, but producing the same amount of protein, while then rewilding/reforesting the saved land.

Polycropping with the best area-adapted plant protein foods such as legumes, soy, nuts, seeds, and grains using conservation agriculture presents high potential. Supplying equivalent protein and improved nutrition, while storing more carbon, should be minded as the real benchmark for sustainability.

Rewilding not only stores the most carbon but is also essential for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Biodiversity conservation of grazing versus rewilding was not within the scope of this paper.

The Rowntree et. al (2020) WOP study claims that SOC sequestration is commonly excluded from Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs). This is simply not true, since there are multiple important articles dealing with the topic, as we have referenced.

Bottom line, we should be evaluating any plant or animal agriculture for the amount of land and other resources needed to produce a set amount of protein, calories, and other nutrients, using conservation agriculture techniques. The most efficient method will sequester SOC, but also use the least land, thus allowing the remaining land to be rewilded or reforested, and also prevents the conversion of more natural ecosystems into agricultural land, by meeting increased human population demands on a smaller total area of land. As such, there is data showing that an extra 4 billion people could be fed, without causing any further deforestation, if existing land used for animal foods were instead used for more efficient plant-based foods.

Does “regenerative grazing” sequester SOC in a linear or unlimited manner?

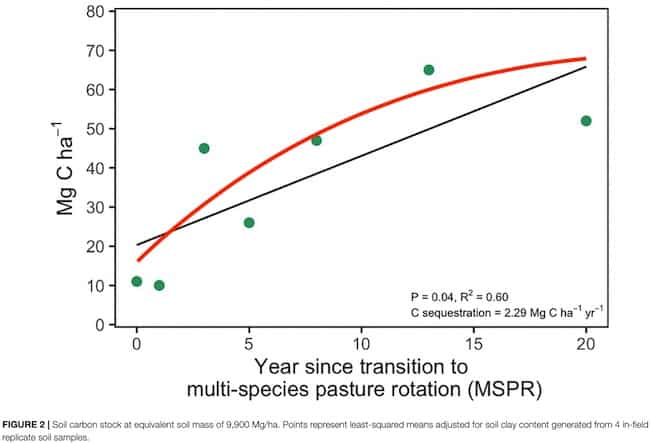

Rowntree et. al (2020) present the soil organic carbon storage as a linear, yearly event in their graph. However, they admit that the first three years were maximal, then slowed, and even peaked by year 13, though they question their own data. Their straight-line could be presented as a curve, such as the red line we superimposed, reflecting nonlinear storage of soil carbon. According to their sampling, there is also variation due to random effects. Yearly fluctuations in carbon storage and release may also be occurring. Small increases in grazing levels may inadvertently release carbon, and the threshold may change as yearly conditions vary, such as rainfall.

It is difficult to base conclusions with only 7 plot points using space-for-time substitution. Numerous spatial samples on a true yearly basis would be better.

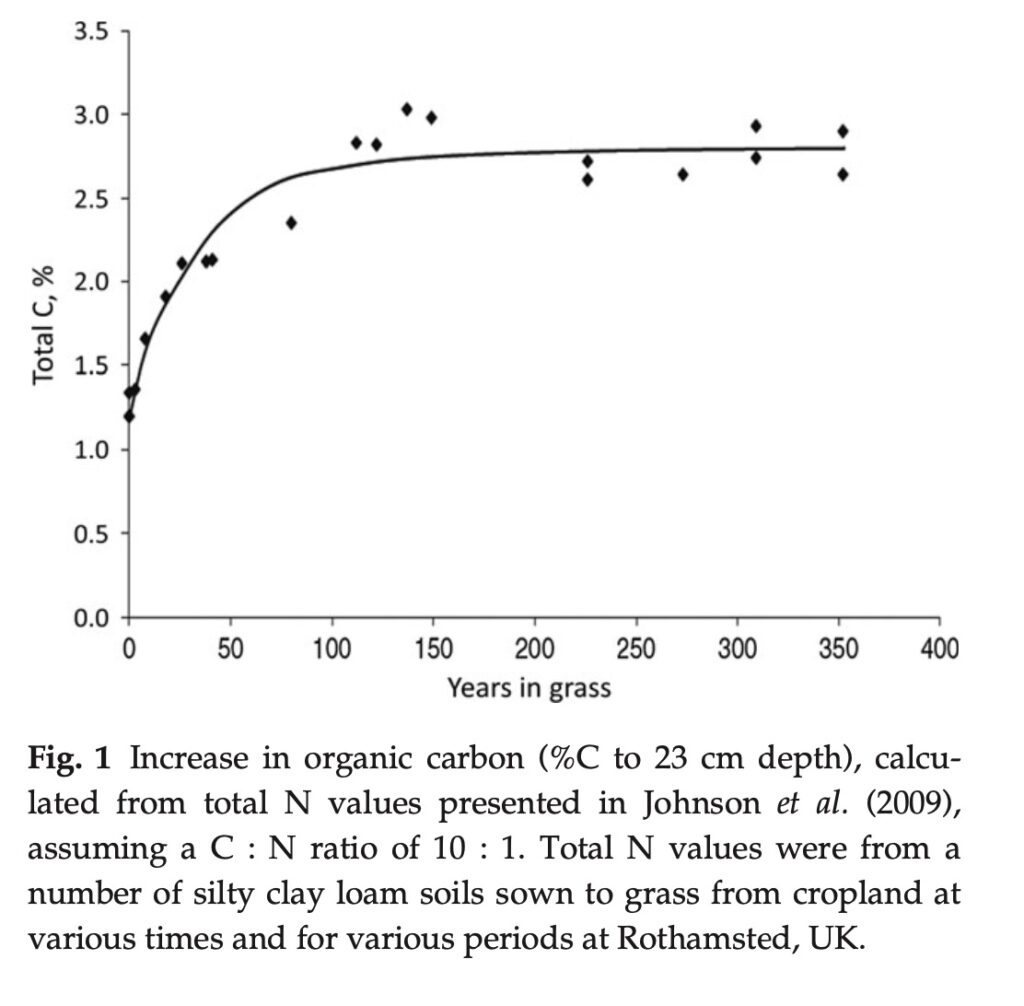

Other studies have demonstrated the process of soil carbon saturation at an equilibrium point. The graph below shows a long term example, partly relying on space for time technique, but also including actual samples that take over decades. The amount, rate, and duration of SOC storage would apply to the specific geographical area measured where the study was done. Also critical is the stocking density, where smaller numbers of animals allow greater vegetation growth. See the graph below from this study 2014 Do grasslands act as a perpetual sink for carbon?

Industry proponents of “regenerative grazing” often implicitly or explicitly exaggerate the SOC benefits of improved grazing techniques, as seen in the recent documentary Kiss The Ground, which makes absurd claims that global grazing could single-handedly solve the entire climate crisis. This would require significant SOC storage year after year, without a reduction in the foreseeable future (i.e. a linear pattern of carbon storage). Unfortunately, the notion is not true.

Once SOC becomes closer to the saturation point, the GHGs (per KG of meat) will be far higher in WOP ruminant meat, more similar to conventional grazing methods.

On page 10 of the Rowntree paper, the authors cite five papers suggesting that components of soil carbon may actually accrue indefinitely. However, when we read these papers, they did not suggest such a claim and in fact, supported the thesis of saturation, with some potential modifiers of the saturation point. As such, this seems to be a misrepresentation of cited sources, and again, inflated advertising of indefinite SOC sequestration by an industry-funded paper. See Appendix 1 below.

Use of references and interpretation of existing literature on optimized grazing

In addition to those mentioned in appendix 1, numerous articles are cited in Rowntree et. al (2020) article, creating the appearance of being comprehensive. Are these references warranted, or dumped into the article for appearance sake? Are their data and conclusions fairly represented? Few may endeavor to review each reference, though we chose a selection from parts of the paper.

As per our review, the findings of these references are often oversimplified and portrayed in a manner implying the importance of grazing for SOC sequestration. However, some of the cited references actually describe the inconsistency around grazing research. They show the inferiority of grazed land compared to natural ecosystems, an overall potential of SOC loss on grazed land depending on various factors, and actually make suggestions for shifting diets away from beef/ruminants. Some also recommend shifting grazing towards intensified cattle farming (i.e. factory farms) as an option to reduce land use and thus restore pasture to natural ecosystems and prevent future deforestation for grazing land. Conant 2017 and Gricom 2017 are two such articles cited in the WOP study, whose findings differ from the way Rowntree 2020 represented them.

Other references in the 2020 WOP study describe the known factors that contribute to improved or optimized grazing. These factors include lower stocking rates (i.e. having fewer animals on an area of land), use of legume cover crops, prevention of overgrazing which may strip vegetation from soil (i.e. having fewer animals and systematically moving their grazing areas), and better manure management to reduce the methane and nitrous oxide emissions that come from manure, and even water flow management or diversion to adjust retention, such as creating ponds. They also show that external fertilizer and water application increase vegetation growth and consequently increase SOC. Ultimately, these are factors that promote dense vegetation growth with the least disruption by cattle. Dense vegetation is what stores atmospheric carbon into plant matter and then to the soil. We agree with all of this, noting that the listed references do not demonstrate that large quantities of ruminant meat could be produced while sequestering significant amounts of SOC. Again, the question of “compared to what” arises. The references suggest that improved practices store more SOC compared to conventional grazing, but as previously stated, they do not demonstrate an advantage over grain-fed ruminant animals, monogastric animals, plant foods for direct human consumption, grown by either conventional or conservation agriculture, or rewilding.

We emphasize that the existing literature shows it is not cattle themselves that cause the majority of SOC sequestration during optimized grazing. It is the improved practices, outlined in the paragraph above, as well as exogenous fertilizer or water, that achieve a higher soil carbon steady state despite the grazing of cattle. Literature promoting regenerative grazing often conflates cause with correlation; especially the error of spurious correlation. When the authors make a sample calculation attributing the entire SOC sequestration to cattle, which would peg WOP cattle at −4.4 kg CO2 equivalent per kg of carcass mass, they could also arbitrarily assign the sequestration to the few rabbits they farmed, and then promote the carbon-negative rabbit “supermeat.” Much more likely, the manure from chickens and pigs fed from off-farm sources is a far bigger factor than cows.

Furthermore, just as in medical science, observational data outcomes should include more studies with relevant control and comparison arms, where optimized and standard rewilding practices are compared to optimized grazing and cropping practices, and further bolster existing literature. That is well beyond the WOP study, but we should recognize the need for such studies with lesser involvement of industry affiliation, whether animal or plant-based.

Grazing advocates suggest that cattle hoof action and dung cause increased vegetation growth. Could hoof action benefit degraded land where the soil was very compacted? Maybe during the initial year of land rehabilitation, but this should be compared to other methods to achieve the same goal. Also, we have yet to see reliable studies comparing such methods. Regarding fertilization, cattle eating and defecating on the same piece of land results in no gain in net soil nitrogen or nutrient content, unless fed using feed grown from off the land sources, in which case there is the transfer of nutrients from one place to another, resulting in loss from one place balanced by gain in another. On the contrary, cattle dung releases both methane and nitrous oxide, which are potent GHGs as mentioned before. The loss of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere is a potential net loss of nitrogen, as are the nutrients in any fecal matter that is washed into streams or groundwater. Ecological impacts of manure are a global problem, lessened but not eliminated by optimal management, including the health aspects.

The WOP/General Mills study claims that their animals use 2.5 times more land in a multi-species pasture rotation (MSPR) system, compared to conventional animal agriculture. As mentioned before, their cattle actually utilize 5 to 6 times the land of conventional cattle, taking feed grown on the land. Their monogastric animals, which were fed from mainly off-farmed sources, should be attributed to the off-farm land actually used to grow their feed but was not included in the calculations.

Consider land use from a different angle. WOP is located in an area of Georgia that used to be scrubland and oak savannas. How much carbon would be released from additional deforestation or land degradation if farmers switched from conventional animal farming to “regenerative” cattle grazing, i.e.the main use of WOP land?

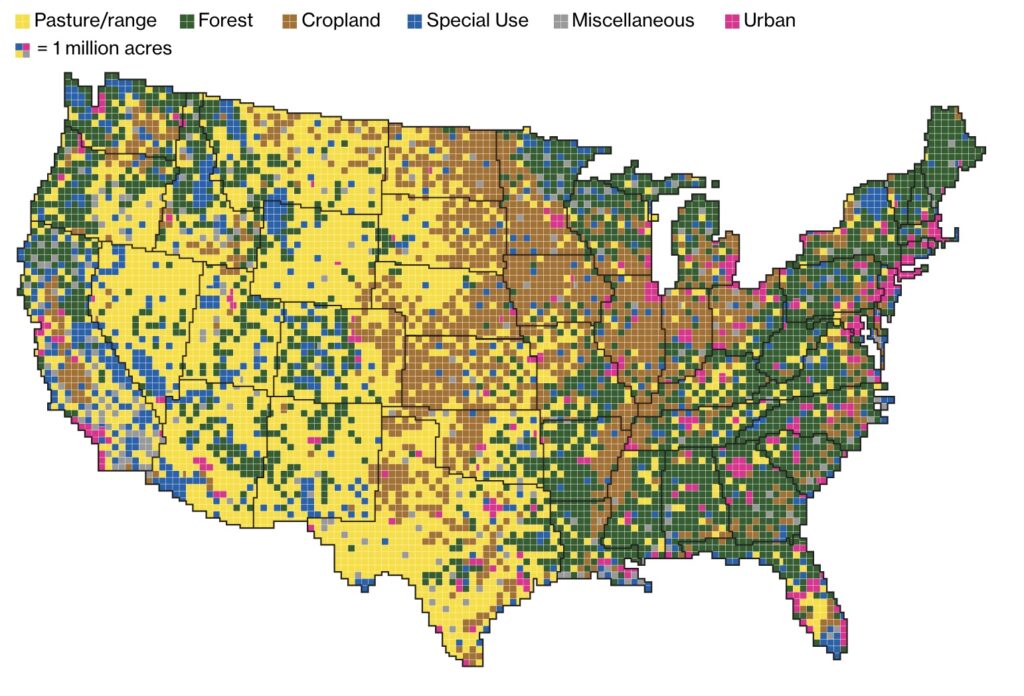

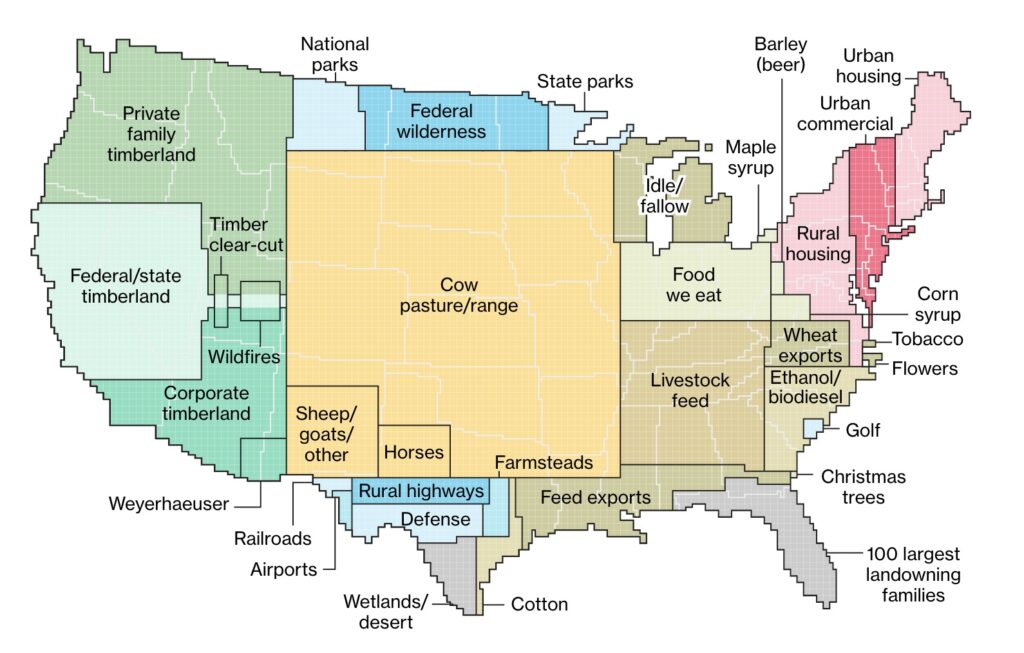

Observe the amount of land used for pasture in the U.S., and the consequence of switching cattle who are conventionally raised on grain (thus utilizing the landmass denoting “livestock feed,” and switching them to grazing. The chart below shows the current breakdown of land use for animal agriculture in the US:

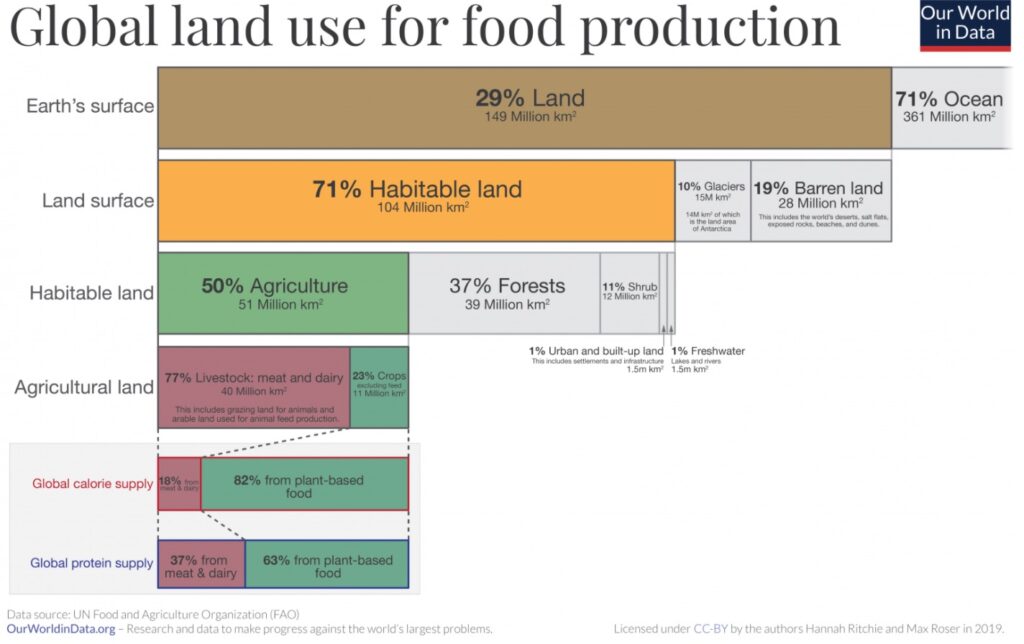

This problem exists on a worldwide scale, since about 45 percent of the Earth’s habitable surface is used for animal agriculture, but returns about 37 percent of edible protein. In comparison, plant foods for direct human consumption utilize about 6 percent of the Earth’s habitable surface and return about 63 percent of human consumed protein. Of the land used for animals, the largest amount is used for grazing.

Rowntree et. al state, “All gasses were converted to CO2 equivalents (CO2-e) using current 100-year global warming potentials (CO2 = 1, CH4 = 30.5, N2O = 265).” However:

More on why methane is not just part of the carbon cycle and how others are creating false narratives that are not backed by credible evidence.

Methods should always be the first area of focus for critique, nonetheless, it is worth considering funding sources in the critical analysis. Industry funding does not discredit a study on its own, but if certain typical patterns emerge, then the effect of an industry motive often has telltale signs.

This industry study conveniently uses a low range estimate of 17 CO2e/kg for beef, which is much lower than non-industry studies that show 29 CO2e/kg, especially those which factor land use impact that have a mean global average of 60 CO2e/kg. Some papers use carcass weight or body weight (which includes bones and other inedible components). A footprint based on carcass weight will be lower than if you do the conversion to actual meat you get from it. These are ways visible environmental impacts can appear to be minimized.

Essentially, there are multiple levels of industry interconnection in the funding and authorship of this study, important lapses in the study, and exaggerated ecological claims. These claims go directly into further marketing of their products, including the notion of “carbon-negative beef.”

Furthermore, just after the publication of this article, as well as recent promotional movies on the subject of “regenerative grazing,” McDonald’s and A&W are promoting their grass-fed and sustainable beef on a massive scale. There is a strong mega-corporate branding strategy for “sustainable beef” at work, beyond only General Mills.

Our literature review caused notice of another disturbing tendency associated with the meat industry. During a New York Times interview, the owner of WOP remarked that the “confederate general Robert Lee” was one of his “heroes,” a man who is known to be a racist and involved in slavery. Note carefully that this does not necessarily reflect the personal racial bias of the speaker or on any person at WOP, but that there are systemic issues. The meat industry is often racialized and has a colonial history in America, and currently in turmoil in places like the Amazon, which is being actively deforested for cattle ranching. Cattle take more land per unit product, and a powerful global industry must get that land from somewhere.

Improved grazing and animal farming techniques, as well as improved plant farming techniques, are known to increase soil carbon sequestration, but the results are modest and time-limited. The WOP farming methods likely do have modestly reduced carbon emissions compared to conventional meat production.

We can credit the study for having the integrity to show the increased land use per unit product from WOP. It also disproves the “carbon-negative” status of WOP pasture overall. However, there are serious potential problems with studies funded by large industries, and this study by General Mills shows typical patterns. All studies require critical review, but industry studies even more so.

The study also has significant lapses that grossly exaggerate or misrepresent the true SOC sequestration capacity of their farming techniques, as well as the actual land used by their animals, especially cattle. To some degree, it still clings to the exaggerated claim of “carbon-negative beef.”

The study proclaims a 2.5X land use figure, an average for the carcass mass of various animals. This masks the actual land use of WOP cattle; likely 5-6X compared to conventional cattle meat. Due to this enormous land use, WOP and “regenerative grazing” techniques have serious climate and biodiversity effects when land use is actually factored in. The study does not even account for the land used to grow the enormous amount of feed for their monogastric animals.

However, the study has significant lapses that are likely to grossly exaggerate or misrepresent the true SOC sequestration capacity of their farming techniques. To some degree, it still clings to the exaggerated claim of “carbon-negative beef.”

Due to increased (2.5X) land use, per unit of meat/protein, the WOP and “regenerative grazing” techniques have serious climate and biodiversity effects when factoring land use. Grain-fed ruminants, non-ruminant meat, and plant protein foods for direct consumption have progressively lesser GHG and other impacts. But the topic of “regenerative grazing” has long been a marketing tool by industry, who are funding their own studies and using the results for marketing purposes.

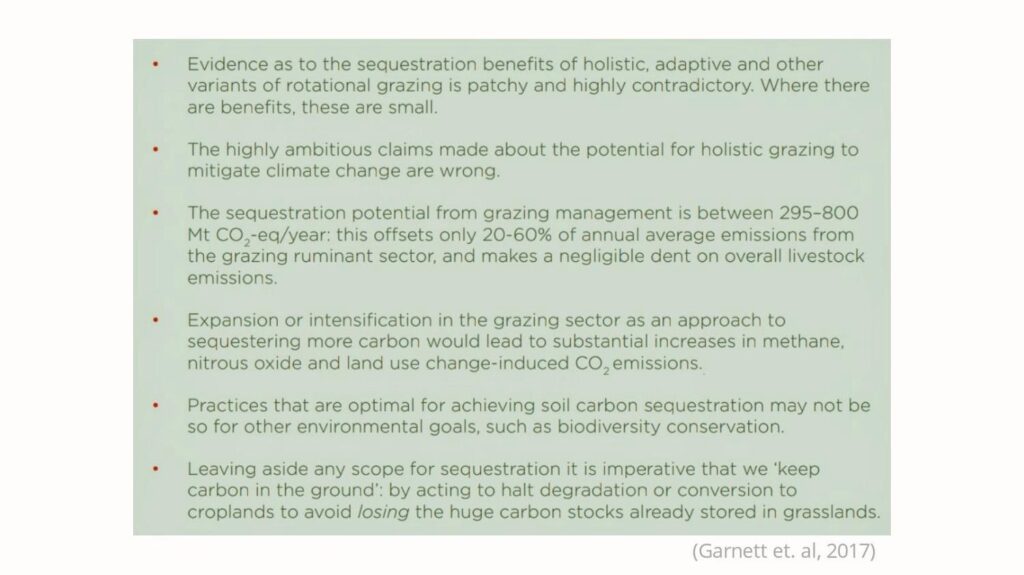

There are many papers outlining this subject over the years, and the recent report by TABLE (formerly the Food & Climate Research Network), is one of the most comprehensive on the issue. Aptly titled “Grazed and Confused,” here are some of the results:

The benchmark for sustainability should be food systems that use the least land to produce an equal amount of protein and calories, such as plant-based foods grown with conservation techniques. Saved land should be used for rewilding, which is the most important factor for SOC sequestration and biodiversity conservation. This recent textbook, Rethinking Food & Agriculture, is a comprehensive academic review of the subject.

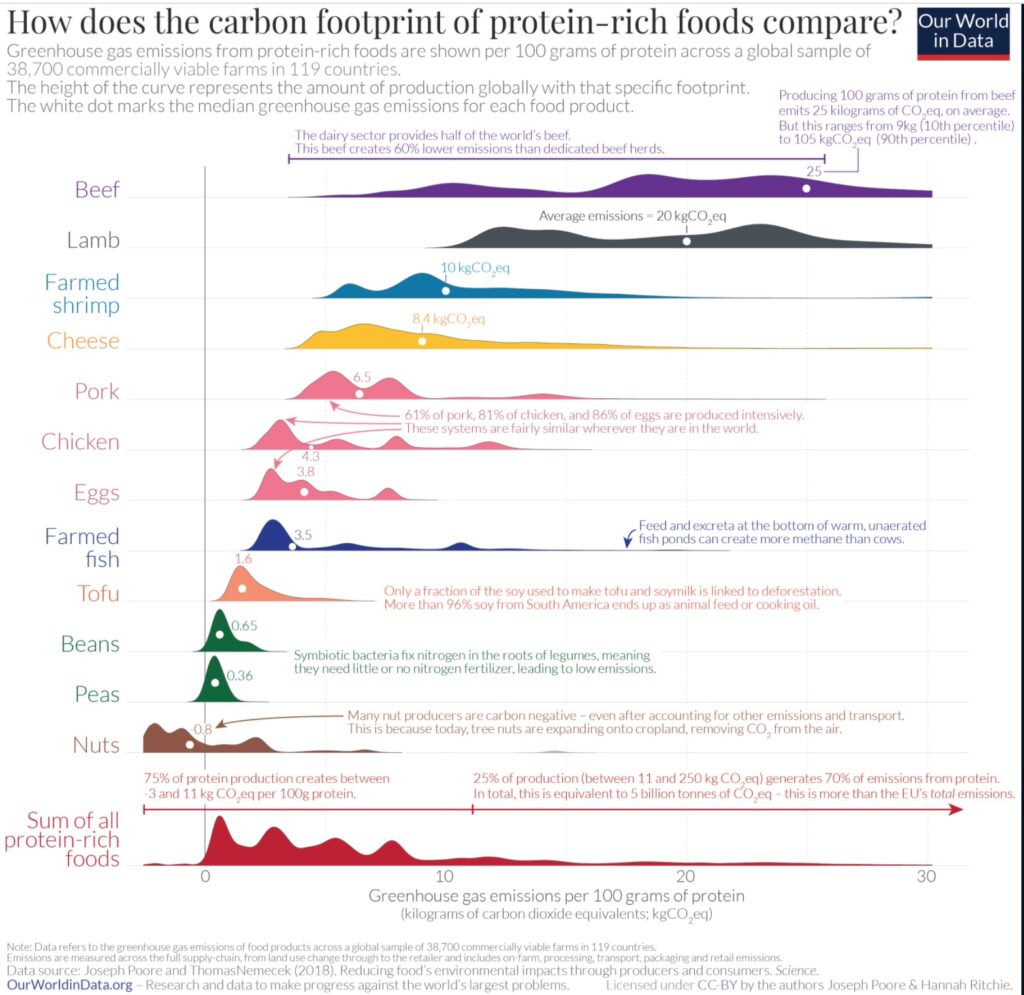

The chart below outlines the potential for the best and worst types of plant and animal agriculture and is a well-referenced summary by Our World in Data.

Here are the five references that are used by Rowntree et al on page 10 of their paper, where they suggest the possibility of indefinite carbon storage on grazed land, rather than saturation. A read of each paper shows that:

a) none of the papers are remotely able to make such a strong claim

b) most of these papers explicitly support the idea of a soil carbon saturation point, including natural variability, and somewhat modified by cropping or grazing practices.

As such, they are an example of exaggeration and inappropriate use of references to make a claim sound realistic. Please read the section on page 10 of the Rowntree paper on “C storage capacity” which leads them to “question the certainty of soil C saturation in grassland soils.” Then download and read the references below for yourself. All of these papers are in concordance with the references which we have used in our article, suggesting the importance of soil carbon, the potential for improved farming, and concur with the limits that other such papers discuss.

2019 Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral-associated organic matter

2014 Sorption of organic carbon compounds to the fine fraction of surface and subsurface soils

2018 Carbon saturation and translocation in a no-till soil under organic amendments