Feature

Budget-Friendly Foods Can Be Better, for Both You and the Planet

Climate•5 min read

Feature

Two new studies reveal decades of industry tactics to downplay beef’s role in climate.

Words by Nina B. Elkadi

In a new paper, University of Miami Professor Jennifer Jacquet and a team of researchers argue that the industry-funded National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) knew about the harms of beef production on climate change as early as 1989 and worked to obfuscate the science. In a subsequent paper, Jacquet and post-doctoral associate Loredana Loy trace how trade groups worked to incite doubt that consumers could make a difference, by choosing to eat less meat, on global climate emissions. There is some evidence, albeit indirect, that these efforts have paid off — a 2023 public poll of 1,404 U.S. adults found 74 percent of them said not eating meat would have little or no impact on climate change.

“Meat and dairy does not want the individual or the consumer to think they have any power, or to think that their choices make a difference at all,” Jacquet tells Sentient. “They’re constantly saying what you do as a consumer will not make a difference. ‘Eating less meat and dairy will not make a difference.’”

Yet a large body of climate research from nonpartisan research groups like the World Resource Institute and EAT-Lancet have concluded that dietary change, in the form of reducing meat consumption, is a necessary component of reducing the anthropogenic effects of climate change.

In a parallel to Naomi Oreskes’s and Eric Conway’s Merchants of Doubt, which details how a group of scientists worked to incite doubt around scientific topics such as anthropogenic climate change and the harmful effects of tobacco, Jacquet’s and Loy’s research describes how the meat and dairy industry worked to create doubt that consumers can take action to address the harmful effects of beef on the environment. “I call them the moo-chants of doubt,” Jacquet says.

In their other paper, Jacquet and her fellow researchers trace how this stems from a history of recognizing, then downplaying, the effects of the beef industry on global warming.

“There is a long, well-documented history of industry attempts to downplay, discredit and even outright deny science that demonstrates the harms of its activities and products. This strategy was honed to a fine art by the tobacco industry; the beef industry now appears to be following the tobacco model,” Oreskes wrote to Sentient.

The question that underlies the research investigating the impacts of industry funding is just how much free will consumers have in their decision-making — especially if the information they receive is flawed.

Trade groups like the NCBA are funded by industry checkoffs, which farmers who sell the commodity pay into on each unit they sell. The checkoff industry is a pot of money worth over $1 billion, and is used for researching and marketing the commodity. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that a commodity program would work to make its commodity look good. But the result, in this case, Jacquet argues, is a misinformed public.

In 2006, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization published a report highlighting the impact of animal agriculture on greenhouse gas emissions. In it, the researchers found that the livestock sector is “responsible for 18 percent of greenhouse gas emissions,” which is a higher share than that of the transportation sector. The report ultimately warns against continuing on with “business as usual.”

In response to this report, Jacquet et al. write, the beef industry commissioned studies to downplay these findings. In 2009, the NCBA gave University of California Davis Professor Frank Mitloehner a grant to investigate the claims made in the FAO report. Throughout his career, Mitloehner has received millions of dollars of industry funding, Jacquet writes, from corporations and trade groups like the NCBA, the National Pork Board and Eli Lilly, funding that was not always disclosed and that in part funded communications efforts to defend the industry.

Jacquet became interested in the origins of the grant, and its goals, and began digging deeper into NCBA archives. Through her archival work, she discovered that climate change was on the industry’s radar long before the FAO report, and that the industry was building plans on how to counter claims that reducing meat consumption could have an impact on the environment.

One of the documents Jacquet uncovered was a 1989 NCBA (then NCA) “Strategic Plan on the Environment,” which acknowledged global warming and the great impact it could have on the industry. The recommendations set out in the plan include taking “a leadership role in positively influencing legislation and regulations,” as well as a campaign to reach “influencers,” then defined as media and educators, as well as lawmakers and the leadership of environmental organizations.

The public relations part of the plan mentions “vegetarian messaging” — messaging that encourages consumers to eat less meat — and included one strategy that recommended establishing “a system for monitoring the media and environmentalist advocacy groups actions.”

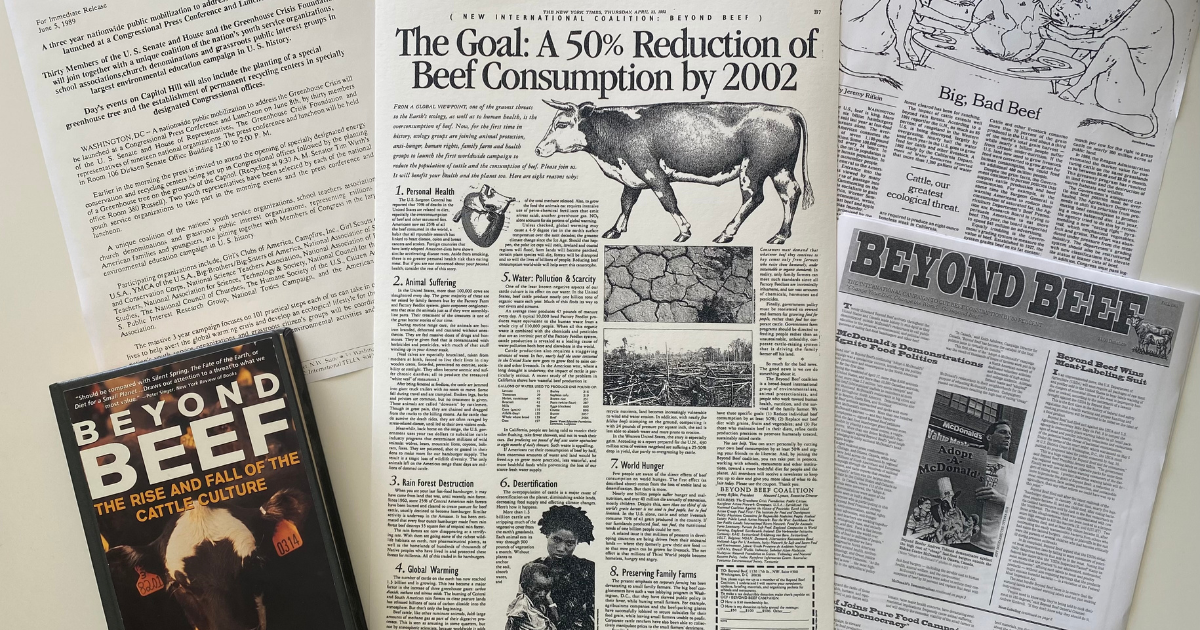

In 1992, a campaign spearheaded by the Beyond Beef Coalition singled out “beef production as a major source of global warming” and encouraged consumers to decrease their beef consumption by 50 percent. The industry fought back with a campaign of its own, Loy and Jacquet write, urging consumers not to blame cows for climate change.

While fighting one campaign with another campaign seems like par for the course in public relations, Loy and Jacquet write that the NCA also urged radio and T.V. producers to refrain from publicizing campaigns like “Diet for a New America” (1990), and funded academic research at Texas A&M to rebut claims made in the Diet for a New America book, such as “it takes 40 times more fossil fuels to produce one pound of protein from feedlot beef than from wheat.”

“They emphasized that individuals would not make a difference, and they also obstructed the sort of public understanding of the role of cows and climate change significantly,” Jacquet says.

When asked for a response on the conclusion of these two most recent papers, Chief Executive Officer of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, Colin Woodall, wrote to Sentient: “The author of these papers takes significant liberties with the information available to her. Correcting misinformation with science-based data, is just one of the essential roles of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, one for which we are unapologetic. The Environmental Protection Agency has calculated beef’s actual greenhouse gas emissions at just 2.3 percent of U.S. emissions. Meaning that any effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by lessening beef consumption would be inconsequential. Any suggestion to the contrary is irresponsible.”

The trade group frequently cites the 2.3 percent figure, which is accurate, but missing important context, according to climate researchers who study food-related emissions. Focusing solely on U.S. emission percentages is misleading, writes Princeton University researcher Tim Searchinger “because overall U.S. emissions are so high.” Per capita, these same emissions would be 24 percent “of an average European’s total emissions and roughly all per capita emissions in sub-Saharan Africa.” Also left out of this figure is just how much beef the average U.S. consumer eats — three times more than the global average.

Changing your diet is one of the few things that an individual consumer can do to impact the climate, Jacquet tells Sentient. As household actions go, shifting to a plant-forward diet is one of the most effective, according to a 2021 study from Project Drawdown.

Reduced meat consumption helps curb how many cows are raised for food. Beef has an outsized climate impact due to the methane they burp into the atmosphere and the massive amounts of land and feed crops required over the course of their lifetime. And cutting back would also have other carbon benefits such as reverting pastureland back to forest and other wild landscapes, which helps keep carbon emissions out of the atmosphere.

Despite the relative consensus on the role of dietary shifts that emerged around 2018, industry misinformation has made its way to most of the public. In their paper, Loy and Jacquet write that “at least part of the reason for civil society’s diminished ambition and hesitation to advocate for dietary change as a climate mitigation strategy was due to strategic opposition by the animal agriculture industry.”

Through the 2000s and into the 2010s, trade organizations were still working against campaigns that encourage eating less beef, Loy and Jacquet argue. In 2021, Colorado governor Jared Polis declared a ‘Meat Out Day’ and encouraged residents to lessen their meat consumption. The Colorado Cattlemen’s Association organized against this, resulting in 26 Colorado counties signing “Meat In” proclamations. The Governor then back-pedalled and declared one day ‘Colorado Livestock Proud Day’ the following week.

The industry campaigns and funding have been so effective in changing public perception, Jacquet and Loy argue, that they have influenced governmental policy and guidance.

“There’s never been a huge buy-in on behalf of the government to address consumption,” Jacquet says. The Biden administration’s 2023 plan to reduce methane emissions did not mention reducing beef consumption once, for instance. “There’s a lot of talk about tweaking production methods, very similar to how it is now with feed additives. Not about reducing head counts, by the way, but about proving efficiency. That is the grand narrative, I think, that we are all operating under.”

Disclosure: Naomi Oreskes advised the author’s undergraduate thesis and the author has worked for Oreskes as a researcher.