Explainer

Why Eating Organic Isn’t a Climate Solution

Climate•8 min read

Analysis

New research shows Canadians can reach their climate goals by reducing meat and dairy consumption.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

A new commercial has played on repeat across Canadian television since June — showcasing hard-working farmers who “preserve the land,” “take care of others more than themselves” and are “all-in” to cut the environmental impact of dairy farming.

Paid for by industry advocacy group Dairy Farmers of Canada, the spot highlights a commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050. While the pledge offers little in the way of specifics or accountability — unsurprising for the food and agricultural industry — the commercial highlights on-farm efforts to reduce climate emissions like crop rotation, solar energy and biodiversity protections.

According to a new report, however, Canadians should look to another strategy to reduce their agricultural emissions — a solution that Dairy Farmers of Canada isn’t likely to make a commercial about — substantially reducing our intake of red meat and dairy products.

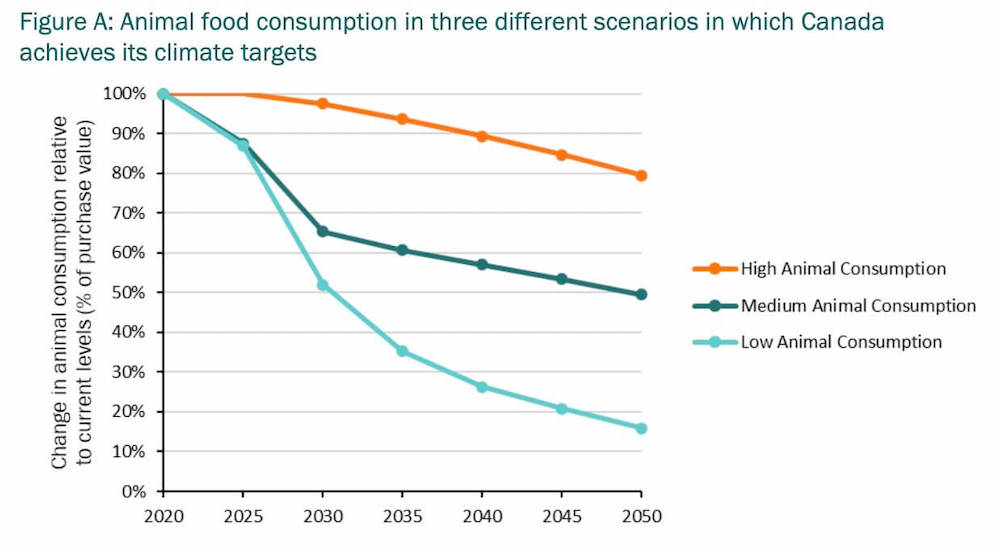

Published by the non-profit organization World Animal Protection and energy-economy research consultancy Navius Research, the report found that Canada can cheaply and effectively reach 2030 climate targets if meat and dairy consumption is reduced by 30 percent, and reach net zero emissions by 2050 if meat and dairy consumption is cut in half.

As reported in the National Observer, Canada’s agriculture sector currently emits 91 megatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions per year, accounting for around 12 percent of the country’s total. The highest contributing source to food-sector emissions comes in the form of enteric methane — primarily cattle burps. Agriculture is responsible for 24 percent of Canada’s overall methane emissions.

“There’s been no acknowledgment [by the Canadian Government] of animal agriculture as a major contributor to climate change,” says Lynne Kavanagh, farming campaign manager at World Animal Protection. The group set out to provide evidence specific to Canada in an effort to demonstrate the urgent need for country-level action. “There is so much data already globally on the connection between animal ag and climate,” she says, but very little on Canada.

The new research looks at the role Canadian animal agriculture plays in increasing climate emissions, and whether a dietary shift could help the country reach its emissions targets.

It would, the report found.

One of the things the group wants the Canadian government to do is to finally recognize animal farming as part of the problem, Kavanagh says. The next step, she adds, would be to “start promoting more plant-based eating to align with Canada’s Food Guide.”

In 2019, the federal government published a new food guide encouraging Canadians to choose plant-based proteins more often than animal sources. Dairy was also removed as a designated food group altogether. Regulators cited environmental concerns as one motivating factor behind the major shift from the meat and dairy-heavy food guides of the past. Yet since 2019, the Canadian government has mostly avoided including animal farming or much of any other food system change in their climate action plans.

While the federal government has shown some interest in financially supporting Canada’s plant-protein sector, current investment pales in comparison to the government’s continued financial bolstering of animal agriculture. The Canadian government is a major investor in the meat, dairy and egg industries. “Animal ag is a huge economic driver in Canada,” says Kavanagh.

According to Nation Rising — a Canadian non-profit working to shift government subsidies from animal agriculture to plant-based food production — the federal government committed well over $1.7 billion in subsidies to animal agriculture in 2021, and millions more have been contributed at the provincial level. For comparison, Prime Minister Trudeau pledged $100 million to the plant-based food sector in 2020.

According to the report, if Canadians reduce their consumption of animal products, the country would also save money, costing the economy 11 percent less to comply with the 2030 emissions reduction targets, “compared to a future where animal consumption remains at the current level,” Kavanagh explains.

Kavanagh says she has seen mixed reactions from the public as a result of the report, but she believes more people are coming to realize the undeniable consequences of animal farming upon the planet and the animals. “There’s a growing understanding of how animal ag impacts climate,” she says. “And of course, more people are concerned about how the animals are treated, too.”

She also believes Canada has the potential to become a leader in reducing food-sector climate emissions. “Experts are calling for wealthy nations to eat less meat and dairy, saying that we have to do it to reach climate change targets and basically prevent catastrophe,” she says. “Canadians eat a lot of meat. We eat twice the global average. That alone shows there is huge potential. There’s room to reduce.”

This story has been updated.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.