Perspective

The Government Wants You to Eat Real Food. But What Does That Actually Mean?

Diet•4 min read

Reported

Workers and residents say companies have downplayed avian flu, burning and burying culled birds just outside of town.

Words by Patricio Eleisegui

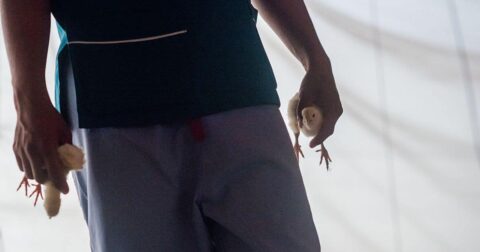

Warning: this story contains a graphic image of culled birds.

The chicken farms are already back up and running, a person close to Bachoco farms in the Yucatán region of southeastern Mexico tells me. “Everything was disinfected and the birds were replaced,” he says. Business as usual. The official count of culled birds for the region is 1.7 million. Yet according to interviews conducted with four farm workers, the actual numbers for this current outbreak of avian flu are nearly twice that — 15 mega-farm have slaughtered closer to 3 million infected or potentially-infected birds.

These same sources also say the companies have disposed of the chickens in unsanitary and potentially dangerous ways. Residents who live in Mayan Indigenous villages near the contaminated facilities, including Samahil and Kinchil, report smoke from farms burning culled poultry and heaps of dead birds disposed of in nearby woods. Photographs shared by employees reveal hundreds of dead chickens buried in the woods near farms, with no explanation from regional poultry companies.

The sources interviewed have asked to remain anonymous, fearing the company’s response: “Farm employees are forbidden to talk about what happens,” says one source. “They were threatened with dismissal.”

Yucatán has had the most infected farms in Mexico, with 16 contaminated facilities in total. Most farm workers are back to their regular work schedules, says a source close to the poultry production companies who remains anonymous for fear of recrimination.

“What they have done is shift some workers from one farm to another,” taking them to different facilities that have remained open. It’s as if the businessmen regulate themselves, says one of the workers.

Most of the 3 million birds come from egg production facilities. According to the workers, the bodies of culled chickens were either dumped in jungles in the southeast of the country or buried near farms.

Residents of the town of Samahil describe finding piles of birds gathered on land near the facilities that poultry company Crío owns in that town. Back in the town of Kinchil, smoke from burning chickens, hens and turkeys filled the air for a good part of December, according to residents.

One Kinchil resident told me, “in the village there is a farmer who breeds exotic birds. Peacocks, among other species. All those birds died from bird flu. The little birds, the pigeons, that roamed the farms were also dying. The only birds that seem to be unaffected are the vultures,” he added, “which are scavengers. And the herons.”

Many workers and residents alike blame the companies. “They completely stopped vaccinating hens and chickens at least 15 years ago,” said one worker, who said the farm operators have cited rising costs for the change in protocol. “They said that the doses per animal were very expensive. And that since there had been no new cases. The disease was not going to return.”

Avian flu has affected local egg prices dramatically over the last three months. In Yucatán and the neighboring states of Campeche and Quintana Roo, a 30-egg pack went from costing 60 Mexican pesos (just over $3 US dollars) to selling for as high as 120 Mexican pesos (around $6.50 in U.S. dollars).

The Mayan communities that neighbor the farms report that some of the specimens infected with avian flu were stolen from the discard areas set up by companies and then consumed by the population.

“I ate a buried chick. I had already eaten some delicious tacos when someone told me ‘that chick you ate was sick,’” said a journalist covering the story. And I stayed like that, with a surprised face. For me the chicken was well cooked, the meat looked normal.”

Fernando García Gómez, a veterinary expert from the University of Mexico, says the risk of catching avian flu from eating infected poultry or eggs is rare, but possible if these foods are undercooked.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, “while there is no evidence that anyone has gotten bird flu after eating properly cooked poultry products,” there is evidence of “a small number of infections” (outside of the U.S.) from “uncooked poultry and poultry products (like blood).”

“Cases have occurred due to the consumption of raw foods based on chickens or hens,” says Gómez, “For example, eggs or offal.”

Most human cases to date have come from handling infected birds. Farm workers come in ”contact with fluids, blood or feces of contaminated birds,” says Gómez, then “when they go to their villages or their homes,” they bring the virus with them, sometimes on their clothing or shoes.

Since the beginning of the outbreak, poultry and egg producers have minimized their role in disease spread.

Earlier this year in January, president of the Yucatan Poultry Farmers Association Jorge Puerto Cabrera declared that the situation was under control and that news about disease spread was unfolding “in an exaggerated way.”

“Yes, there was avian flu,” he said. “We had to slaughter birds, vaccinate those that were disease-free and be more aware.” Still, Cabrera insisted, “the number of affected farms is very small.”

Not only that but perhaps migratory birds were to blame, he suggested — a Eurasian duck or kau traveling south for the winter. Of course, wild birds can spread avian flu — something wildlife researchers in Latin America have been warning about since the summer. But the overwhelming majority of disease outbreaks take place on factory farms. Just over 6,000 wild birds have been affected by avian flu in the U.S., for example, whereas farmed birds infected or culled total a staggering 58 million, with no end in sight for this outbreak.

Despite several attempts to reach poultry and egg producers Crio and Bachoco, Sentient Media received no response or comment to this story.