Solutions

West Hollywood Committed to Plant-Based Food. Here’s What That Looks Like So Far

Climate•6 min read

Feature

Thirteen civil rights complaints, including from communities impacted by poultry farm pollution, have been left in limbo.

Words by Grey Moran

Since the beginning of President Trump’s second term, the Environmental Protection Agency has not been allowed to accept new civil rights complaints or issue any findings of discrimination for existing complaints, according to former and current agency staff who spoke with Sentient. These informal directives have limited the EPA’s capacity to enforce Title VI of the Civil Rights Act — a provision of the law that requires recipients of federal funding not to discriminate, whether intentionally or not. In the past, the provision has been used to challenge government-sanctioned environmental racism, including the rubber-stamping of polluting industries in neighborhoods that are majority Black, Indigenous or people of color.

These latest restrictions on civil rights investigations have coincided with more sweeping, disruptive changes hitting the EPA’s environmental justice offices, which were ordered to close on March 12th. While the agency’s civil rights office has been spared so far, its enforcement has been weakened — frustrating staffers, communities and civil rights lawyers.

“This is a moment of uncertainty. I can promise that we are committed to civil rights and environmental justice, and we will continue that fight. But I can’t say more than that at this moment because so much is in flux,” Debbie Chizewer tells Sentient. Chizewer is an attorney at Earthjustice who has represented communities in filing Title VI complaints to the EPA.

During the first few weeks of Trump’s return to the White House, the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights’ management was provided with no instructions on how to proceed with their mandate to administer and investigate civil rights complaints, so they instructed staff to take the route of least resistance — pausing nearly all activities associated with civil rights oversight. For a period, the EPA’s civil rights division was under a near-total ban on external communication — including with other agencies, EPA regional staff, complainants and lawyers representing complaints, according to two sources with close knowledge of the office.

The communications freeze ended in February and the office’s staff began engaging again with complainants and lawyers, moving forward with existing investigations that had been stalled, according to the same two sources, who asked for anonymity out of fear of reprisal.

However, as of late March, the EPA’s civil rights team was still barred from opening up new investigations, while also restricted in how it carries out these investigations. The office is not allowed to draw any conclusions, known as “findings,” based on evidence gathered over the course of its investigations. This includes findings of discrimination, a determination that an EPA funding recipient violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

The office is allowed to review complaints, but if the complaint meets the criteria for opening an investigation, staff aren’t allowed to accept it, according to the same sources. For now, the complaints are languishing in the agency’s queue, with no timeline for when they will be processed. The office’s management also began meeting with, and running decisions about the complaint process by, Travis Voyles, the assistant deputy administrator of the EPA appointed by the Trump Administration.

“My fear is that they are never going to let the work proceed,” a former EPA staff member, who asked for anonymity out of fear of reprisal, tells Sentient. The source also expressed concern over how the Civil Rights Act, including Title VI, is being weaponized to threaten withholding funding from institutions that do not comply with the Trump Administration — an unprecedented use of this provision that has not once been used to withhold funding in the EPA’s history.

“Especially with this spate of actions targeting unexpected entities like law firms and universities, I can see a world where complaints against state agencies that are let’s say ‘friendly’ to the administration would be rejected but complaints against agencies that are ‘unfriendly’ to the administration might be allowed to go forward,” says the source.

The EPA’s enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act — distinct from its enforcement of environmental laws — largely target local and state government-sanctioned discriminatory practices on the basis of race, color and national origin. This offers a rare legal tool for fighting a quiet, insidious form of discrimination, often called environmental racism — as communities of color tend to be disproportionately exposed to pollution and other environmental hazards. As climate change worsens, Black communities in particular are more likely to suffer from property damage, flooding, displacement and health consequences from heat and toxic exposures.

The agency has long struggled with fully enforcing this provision of the Civil Rights Act — just take a glance at where waste incinerators are located in every U.S. city, the communities in Alabama’s ‘Black Belt’ still lacking access to sanitation services, the hog farms in North Carolina that are more than four times likely to be sited in a Black community — but now the future of the agency’s Title VI enforcement is even more uncertain as the Trump Administration launches an attack on civil rights, which it tends to call DEI, across agencies.

Historically, the EPA has rarely issued findings of discrimination. Instead, the potential for a finding was used as a bargaining chip to negotiate a stronger resolution agreement, a mutual agreement outlining steps for alleged violators of Title VI — often state and local agencies that receive EPA funding — to come into compliance with the law, without any penalty.

“In many situations, having the [EPA] come in and issue findings would add pressure to the funding recipient — the state or other actor — to come to the negotiating table with a serious offer to change practices,” says Earthjustice’s Chizewer. “So having a policy that excludes that possibility could reduce the pressure on the funding recipient.”

There are currently 30 active civil rights complaints at various stages of the EPA’s process for reviewing, investigating and resolving alleged violations of Title VI, filed by largely Black, Hispanic and Indigenous communities across the country to seek relief from environmental contamination and health hazards.

These include Black and Indigenous residents in North Carolina surrounded by hog and poultry farms that spill animal waste into the rivers and groundwater, Black residents in Port Arthur, Texas living nearby a Koch-owned plant that rains sulfur that coats their neighborhoods in yellow and black dust and a Black neighborhood in Hartford, Connecticut that suffers from flooding and sewage overflow every summer — to name just a few of the communities still awaiting justice before the EPA.

Compared to the EPA’s environmental justice offices, which have placed 160 employees on paid leave, the agency’s Office of External Civil Rights Compliance (OECRC) has remained mostly in-tact: two probationary employees were terminated and then placed on administrative leave; a student intern was terminated; one employee resigned willingly and another employee has been reinstated after being erroneously terminated for environmental justice activities, according to two sources familiar with the matter.

Even though the EPA’s small office of under 20 staff is still mostly preserved, its capacity to carry out its work is still disrupted by these informal directives.

Marianne Engelman Lado, a civil rights attorney who served as the acting principal deputy of the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights (OEJECR) during the Biden Administration, spoke on record, telling Sentient that “in terms of career leadership and direction, the office has already been diminished,” referring to the civil rights division. Just prior to her leaving the agency, Lado says that the process to hire a new director of the EPA office tasked with handling external civil rights compliance had begun. But since Trump’s second term began, that effort was effectively halted.

“Since that time, as I understand it, the offer to the director has been retracted,” says Lado, with no progress made to fill the role. “There is no effort to have a permanent director, to my knowledge.” The director position is currently listed as “vacant” on the EPA website.

There is little clarity right now, however, Lado stresses, and many speculative moving pieces. “In order to reorganize, any agency needs to take steps such as notify Congress, work with the unions,” says Lado. “I have not yet heard that the administration has taken those steps.” Beyond that, “it’s not clear what will happen to those portions of the office that have a statutory mandate,” which includes its civil rights division, says Lado.

The shuttering of the environmental justice office was something that EPA staff were bracing for, given that this is outlined in Project 2025, the blueprint for the current administration. This office was established early on in the Biden Administration, bringing together environmental justice and the office tasked with civil rights under one umbrella. Lado anticipates that the civil rights division will be preserved, given its statutory obligations, but potentially moved to a new location within the federal government.

Other federal civil rights enforcement teams have faced deeper cuts. The Department of Education’s civil rights office, which is the largest civil rights office in the government, recently laid off at least 240 employees — nearly half of the office’s total staff. The Department of Homeland Security’s civil rights team has placed 100 staffers on leave, effectively dismantling the office’s capacity to enforce civil rights. However, these offices have not been ordered to close, which would be more difficult given their statutory and regulatory obligations.

Instead, the Trump Administration is gutting the civil rights divisions from within. “They diminished it. They harmed it. They made it more difficult for that office to do its work,” says Lado, speaking about the cuts to the DOE’s civil rights office.

Regardless of the cuts however, federal agencies are obligated to enforce the Civil Rights Act. The EPA, for instance, is regulatorily required to review and process complaints. “I’ve sued EPA successfully on this, when they were taking decades to resolve complaints,” says Lado, who previously worked as a lawyer at Earthjustice, representing Title VI complaints. “They have an obligation to resolve these complaints in a timely way.”

Over the past several years, rightwing pressure has been building to urge the EPA to back off from enforcing Title VI. Last year, a group of Republican attorney generals from 23 states petitioned the EPA to rescind a key part of its Title VI regulations, requiring disproportionate racial impacts to be considered in environmental decisions. This was prompted by a 2023 court case in Louisiana, which the agency lost, barring it from enforcing disparate impacts in Louisiana.

The decision ended up having a much wider chilling effect in how the agency proceeded with Title VI enforcement. “This [Louisiana] case shifted the internal culture of agencies reviewing Title VI complaints,” says Mia Montoya Hammersley, an attorney and the director of the Vermont Law School’s Environmental Justice Clinic. Even before Trump’s election, she says, the EPA began shifting away from considering disparate impacts, in light of the prospect of legal challenges in other states.

The EPA’s Title VI enforcement began to shift to be more narrowly focused on intentional discrimination, which is more challenging to prove. Many cases of environmental racism tend to involve governmental neglect and more indirect actions that enable polluting companies.

“It’s just very disheartening to see not just this, but many tools geared towards addressing disparate harm being chipped away,” adds Montoya Hammersley. “This is really aligned with this larger cultural shift that we’re seeing towards color-blind regulatory structures.”

Chizewer views the Trump Administration’s current attacks on civil rights as part of a larger, coordinated effort to erode civil rights protections, drawing upon similar narratives to redefine what counts as discrimination and how it is enforced.

“I see the current actions of the administration as the logical progression of the arguments that we’ve seen over the last several years that are designed to undermine civil rights and environmental justice,” she says. She sees a parallel in the language of the current executive decisions and the EPA petition filed by attorneys general, including the “notion that efforts to protect communities that are experiencing disproportionate harm is some form of its own racism.”

As the Trump Administration has moved to delete portions of federal websites, Sentient has created a copy of the EPA’s Title VI complaint docket, which includes copies of complaints, rejections and resolutions. (It’s available in editable form as a zip file, or non-editable as a Google Sheet.) Spanning between 2010 and 2025, the docket confirms that the EPA has not accepted any new complaints since Trump took office. Though the agency has moved to reject five Title VI complaints under the new administration, 13 complaints have been left in the queue, awaiting a review.

There are also 9 active investigations, including one from David Ludder, a civil rights lawyer who filed a complaint against the city of Dothan, Alabama, where a landfill is set to expand to over 500 acres, saddling largely Black neighborhoods with more pollution.

Ludder says he has not received an update from the EPA since Trump took office and is not confident that the ongoing investigation will prompt substantial change for Dothan communities.

“‘I think the program is virtually — I don’t want to say dead, because it could be revived someday — but it’s in a coma,” says Ludder, in an interview. “It probably won’t be revived under the current administration.” Instead, he says he plans to pursue other avenues for protecting the environment, including an ongoing state lawsuit over the landfill.

The EPA has reached three informal resolution agreements with agencies accused of violating Title VI, outlining how the agency will come into compliance. Arriving at resolution agreements is a primary objective of the EPA’s civil rights division, which is required to “attempt to resolve complaints informally whenever possible,” according to the agency’s regulatory requirements for Title VI enforcement.

While three resolutions may look like a mark of progress, these agreements don’t always indicate that a community’s concerns have been addressed. In actuality, the results may be more like watered-down resolutions to move complaints more quickly out of the system. This was a pattern that was encouraged under the first Trump Administration, according to a former EPA staffer who asked for anonymity because he still works for the federal government.

“Just because the case is closed, it doesn’t necessarily address the complaint or the issues, right? And I saw that a lot,” the source tells Sentient. “It essentially could be a slap on the hand.”

This pattern appears to have continued with a recent resolution agreement reached on March 12th with the EPA Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health over issuance of a new air permit for a gas-fueled electricity generator at the Wayne Junction rail station. The plant has been protested by locals for a decade for polluting the predominantly Black neighborhood of Nicetown, which has one of the highest rates of childhood asthma hospitalizations in the city.

“If you go along the rail line, and you go up the rail line into Chestnut Hill, the air is fine. At the same time, the air down in Wayne Junction is not,” says Peter Winslow, who is an activist with the interfaith group POWER that filed the Title VI complaint in 2021. He was initially hopeful that this process would result in long-sought relief for residents.

“They were much better under Biden, and we had good communication. With the Trump Administration, that all got shut down.” he says. He says he used to be able to call the agency to talk informally about his complaint, but this stopped once Trump returned to office — coinciding with the period when the civil rights division was not allowed to communicate with the public.

His hopes were ultimately dashed when he received an email with the resolution agreement — one that sidestepped most of the community’s concerns and requests. “Much of what the city has agreed to do are things that were not part of our complaint at all,” says Winslow. “They have improved their process for grievances and in terms of their employment practices and providing information to people in languages other than English and with disabilities, which is a very good thing to do, but is not what we were complaining about.” Winslow was hoping the resolution agreement would result in a plan for the regional transit authority to reduce pollution in Nicetown, among other relief.

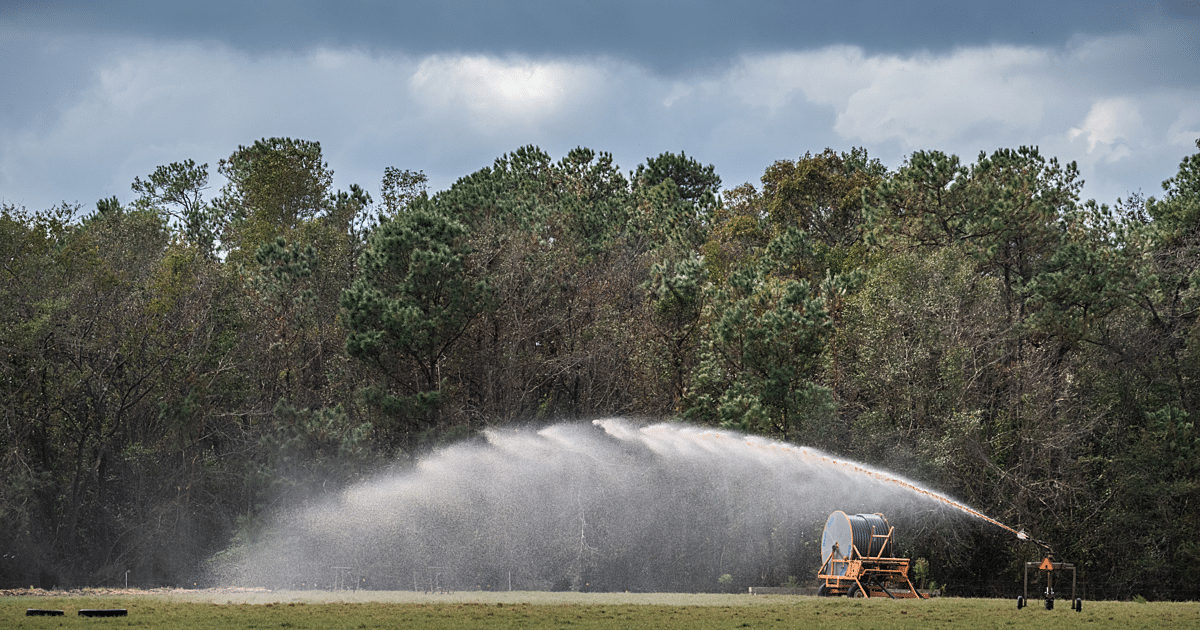

In North Carolina, the EPA is in the process of negotiating with the state’s environmental agency over a complaint concerning the permitting of hog farms. These farms are highly concentrated in a region known as the Black Belt, which the complaint describes as “the crescent-shaped swath of dark, fertile soils stretching from Virginia to Mississippi where large numbers of African Americans were enslaved on plantations before the Civil War.” Many Black residents have lived along North Carolina’s eastern plains for generations, alongside Indigenous tribes.

But this region is becoming less and less livable as longtime residents become overcrowded by the more than 2,000 industrial hog operations in the area that raise around 9 million hogs. These many millions of hogs produce 10 billion gallons of waste per year, sprayed on fields as fertilizer, but in practice also seeping into the streams and groundwater supply. The waste is also flushed into open air pits, known as lagoons, that emit methane, ammonia and other pollutants.

“This is a rural part of the state where the majority of folks rely on well water for drinking water, and a lot of people just don’t trust their water. They live close to hog operations. Their water tastes funny,” says Blakely Hildebrand, an attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, who is representing the North Carolina NAACP and North Carolina Poor People’s Campaign.

The complaint challenges the permitting of four new operations to collect methane from the lagoons and use it as “biofuel,” injecting it into natural gas pipelines. While billed as an environmental solution by the hog industry, the complainants contend that “industry-sponsored biogas projects exacerbate this long-standing environmental injustice by increasing the risks of the polluting lagoon and sprayfield system.” Three of the operations are sponsored by Align RNG, a joint venture of Smithfield Foods and Dominion Energy.

“You can’t let your children go outside and play like you should because of the air in Duplin and Sampson Counties,” says Deborah Maxwell, the president of the North Carolina NAACP. “Talking about particulate matter going across people’s yards, the inability to even sit outside and hang your clothes out, which is a Southern tradition.”

Hildebrand says that she’s received “no indication” from the EPA that they are no longer engaged in the information resolution processes, and she remains “hopeful” about reaching a resolution. “We are proceeding as we have been until we hear otherwise from EPA,” she says.

As the administration continues its efforts to undermine civil rights, Marianne Engelman Lado is holding onto hope too. “It is particularly sad to see this wrecking ball aimed at environmental justice. It will not be successful,” she says. “The communities that are overburdened are going to continue the struggle for justice, and many states will pick up the ball.”

Note: Sentient reached out to the EPA for comment and was directed to the March 12 press release referenced above.