Southwest Wisconsin Dairy Operation Linked to Spill Affecting Eight Miles of Trout Waters

Climate•4 min read

Analysis

“We’re in an apocalyptic phase for animals in CAFOs.”

Words by Karen Asp

The first half of 2022 ranked sixth warmest on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The high temperatures and lack of water can cause serious health problems for people, even death, but heat and drought are also devastating for billions of farmed animals, especially those raised in concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs.

We don’t have exact statistics for how many farmed animals are dying from high temperatures or drought, but just one 2021 heat wave in British Columbia, Canada wiped out 651,000 chickens in one week’s time. The number of poultry deaths came from livestock industry emails, made public thanks to a freedom of information request.

Thanks to the lack of transparency and oversight for industrial farming operations in the U.S., we don’t know whether livestock producers are taking extra measures to keep animals comfortable when temperatures rise and water dries up. But we do have some startling statistics that show just how many farmed animals are living in these sweltering conditions.

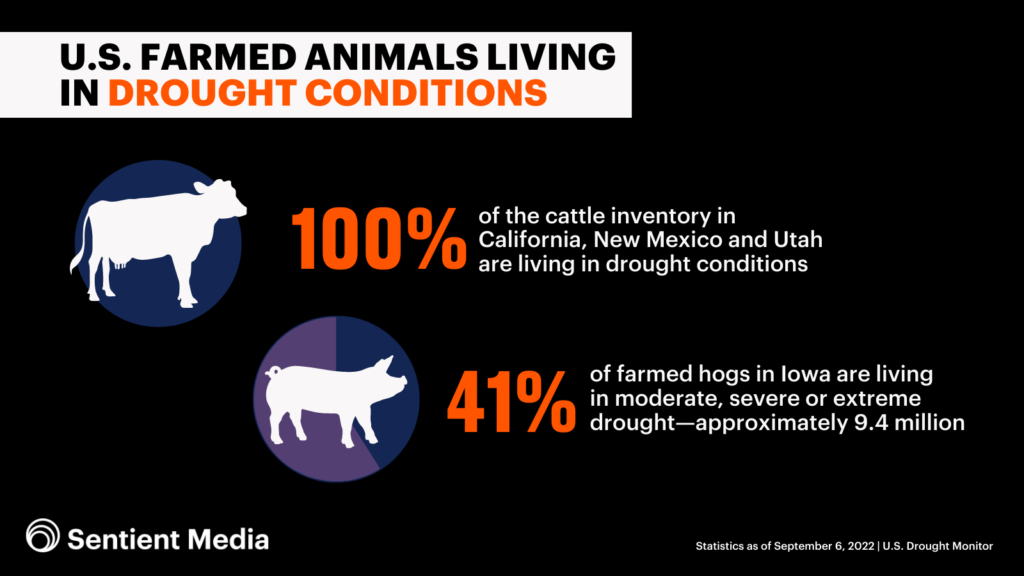

According to U.S. drought monitor figures, 41 percent of farmed hogs in Iowa were living in moderate, severe or extreme drought during the first week in September. Based on USDA figures, that percentage translates to approximately 9.4 million animals likely experiencing drought conditions. Even worse, one hundred percent of the cattle inventory in California, New Mexico and Utah are living in an area experiencing drought, with 61 percent of California’s farmed cattle living in what researchers describe as “exceptional drought,” characterized by widespread pasture losses and water shortages severe enough to cause water emergencies.

Just as companion animals can develop heat-related illnesses, so, too, can farmed animals. High temperatures can put them at risk of dehydration, which can lead to heat stroke, says Renee King-Sonnen, executive director and founder of Rowdy Girl Sanctuary in Waelder, Texas, and the Rancher Advocacy Program (RAP). The suffering they experience can ultimately result in premature death, especially true for animals raised and slaughtered in industrial facilities.

“We’re in an apocalyptic phase for animals in CAFOs,” says King-Sonnen. Rowdy Girl, for instance, has numerous drought and heat protocols for its animals, like placing fans in chicken coops, freezing jugs of water so animals can cozy up to them and placing ice in troughs to keep the water cool.

“You can guarantee nobody’s going to these lengths for the animals in CAFOs,” says King-Sonnen. In June, for instance, thousands of cows dropped dead from high temperatures and humidity in Kansas. According to the University of Minnesota Extension, cows have a moderate risk of heat stress when the temperature exceeds 80 degrees Fahrenheit and a high risk when the mercury surpasses 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

In the United Kingdom, around four million chickens in CAFOs died in August from heat exhaustion or other heat-related stressors during a record-breaking heatwave. The chickens were “left to die in the heat” when temperatures climbed as high as 113 degrees Fahrenheit, according to The Independent.

Farmed chickens are bred to be much larger than wild chickens. Their large bodies make them more vulnerable to heat stress. A 2011 study found commercial broilers to be more susceptible than the two other wild breeds included in the research. Heat stress causes numerous behavioral, physiological and neuroendocrine changes in these farmed birds, including oxidative stress, which can lead to premature death.

Live animal transport also results in high numbers of heat-related deaths. Every year in the U.S., tens of millions of farmed animals -— 20 million chickens, 330,000 pigs and 166,000 cows — die before they reach slaughterhouses, according to analysis by The Guardian. Heat stress is one of the causes, as temperatures in these transports can reach over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, which can trigger heart attacks. Most of these animals are never given food, water or respite during the journey.

Heat and drought can cause a number of other environmental emergencies that are also linked to animal suffering. Drought can cause mudslides, monsoons and flash floods, while heat can spark wildfires. All of these events can lead to premature death for farmed animals.

Lack of feed is also a problem, and Molidor is especially concerned about cattle grazing in increasingly arid lands in the western U.S. “Grass isn’t there for grazing, and supplemental feed is harder to find and produce,” she says. And in high heat, animals like dairy cows eat less, causing a decline in their milk production.

Cost of hay is another concern, putting a financial squeeze on farmers that often results in premature death for livestock. “Animals, especially cows, are going to slaughter in record numbers, largely because cattle ranchers can’t afford to keep them,” King-Sonnen says. “The lines at sell barns are unbelievable.”

Economic hardships mean farmed animals overall suffer even more. “When economically challenged producers are struggling in heat and drought, animal welfare becomes deprioritized further,” Molidor says.

At the same time, the massive acreage of properties where farmed animals are housed makes providing water to them harder. The upshot of all of this, says Molidor: “In some cases, mass deaths are occurring not only from heat stress but also from starving or thirsting to death, and all of these conditions are horrible ways to die.”

There are no easy answers for eradicating heat and drought conditions for farmed animals, especially with the future looking even hotter and drier.

From Molidor’s perspective, farming needs to change. “In its current state, farming is the leading driver of biodiversity loss,” she says, putting one million species at risk of extinction. She also says industrial agriculture is one of the leading drivers of the climate crisis, which in turn “makes drought worse.”

Farmers can deal with the heat by offering animals additional protection from the elements. One option is to install cooling systems in CAFOs to increase ventilation for animals confined indoors and plant trees to provide shelter for grazing animals. Yet the current food system doesn’t make it easy. “The infrastructure needed to bring relief from the heat to these animals doesn’t exist at the scale needed in a model that prioritizes profit above all else,” Molidor says.

And while heat certainly isn’t easy to combat, the water crisis might be even more difficult. “The sheer scale of animal agriculture is beyond anything feasible in the current and worsening water crisis,” Molidor says. “What’s needed is agriculture that’s shelf-stable, has a low carbon and methane footprint, is water-smart, does not expand land-use, and humane would be nice, too.”

One big-picture solution involves moving farmers away from animal agriculture, something that RAP was created to do. The project is working to transition an Arkansas farm that was once a mega chicken producer into a 100 percent state-of-the-art mushroom farm. There are similar efforts underway led by other animal protection groups, though there are challenges, primarily the steep cost of transition.

Individuals can help by shifting to a plant-based diet – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change promotes plant-based eating as an important strategy for climate action. Government investment in the plant-based sector is also critical, says King-Sonnen. “We need the government to give farmers money to grow plants, not animals like cows which is unsustainable.”

The conditions farmed animals endure during severe heat and drought should give consumers pause, says King-Sonnen. “When you drive by these CAFOs on days when the temperature is over 100,” she says, “you see thousands of cows in conditions that are forced by humans — no barns, no trees, no nothing but the hot Texas sun beating on their back — you have to wonder how humanity has allowed this to be okay.”

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.