Review

What Comes After Industrial Meat? A Future of Meat Without Livestock

Climate•4 min read

Explainer

It’s time to talk about the substantial pawprint of our pets’ food.

Words by Björn Ólafsson

At this point, it’s old news that meat is environmentally unsustainable and needs to be reduced if we have any chance of remaining below 1.5 degrees of global warming. Most of this discourse focuses on humans eating meat. But there’s another factor that’s critical to this conversation: our companion animals, and the environmental impact of pet food.

There are at least 78 million dogs and 58 million pet cats in the United States today, and between 60 to 70 percent of households have at least one pet. Worldwide, we’re talking about a pet population in the 10 digits. That’s a lot of animals, eating a whole lot of food. And because this food is disproportionately made of unsustainable meat, the carbon pawprint of our nation’s pets is a serious issue — especially for all the animals killed to feed our furry friends.

Pet food for dogs and cats is unsustainable, primarily because the content of kibble is disproportionately meat-based. While our companion animals only eat about a fifth of what us humans eat, they eat a third of the meat we consume.

Meat is harming the climate in two main ways: it needs a lot of land (often requiring deforestation of said land), and animals raised for food release methane and carbon in unsustainable ways. Animal agriculture is also contributing to pollution, biodiversity loss and soil degradation across the world. And pets are eating a lot of meat — which shares responsibility for this damage.

Pets themselves are also growing in number; the number of pet parents increased by 18 percent within the last three decades, and we’re seeing similar trends across the world.

According to a 2017 paper, pet food releases 64 million tons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere every single year in the United States alone (give or take 16 million tons). To put that into perspective, if all the pets in the world formed their own country, they would rank 60th in terms of annual emissions.

These findings were corroborated by a 2023 study, which found that a switch to vegan pet food would curb meat and dairy emissions by 15 percent. The researcher also found that a switch from a meat diet to a vegan diet for all pets would create a calorie boost equivalent enough to feed the combined populations of the UK and European Union.

A 2020 paper that investigated the global pawprint of pet food found that kibble is responsible for between 41 to 58 mega hectares of agricultural land worldwide — an area about double that of the UK.

The pet food industry likes to argue that pet food is “rendered” — a term meaning the meat used is inedible to humans and is taken indirectly from slaughterhouses as a byproduct — and would otherwise be wasted. With this marketing tactic, the pet food industry positions itself as a recycler, rather than a polluter.

Unfortunately, this talking point isn’t backed up by data. In 2020, a report from three pet food trade groups investigated the ingredient make-up of pet food and found that 61.5 percent of the meat in pet food was unrendered — meaning rendering comprises only a minority of ingredients. Pet food is also becoming less rendered over time, as pet parents are spending more money on higher-quality ingredients and less on highly-processed rendered meats.

Academics have also criticized this industry argument by saying that pet food requires direct competition with the traditional animal agriculture market, and thus isn’t really a byproduct. Rendering is its own business, with factories, companies, products, market reports, investments and profit margins just like any other industry. The pet food industry’s economic contribution to animal agriculture is unsustainable, not recyclable.

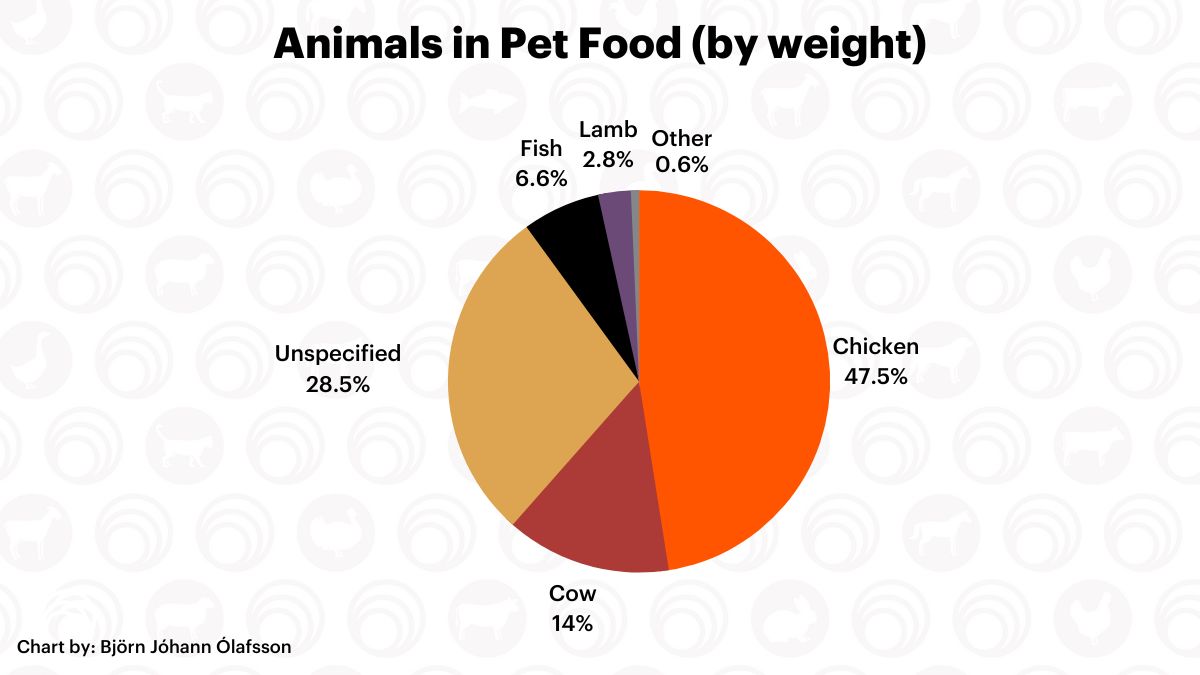

Pet food uses a lot of animals. By reviewing the ingredient labels of that 2020 pet food industry study, we can examine that, by weight, chicken is by far the most popular animal in pet food, with cow, fish and lamb as other animal ingredients. About 28 percent of the meat was not specified, and less than one percent involved a different animal, like pig or deer.

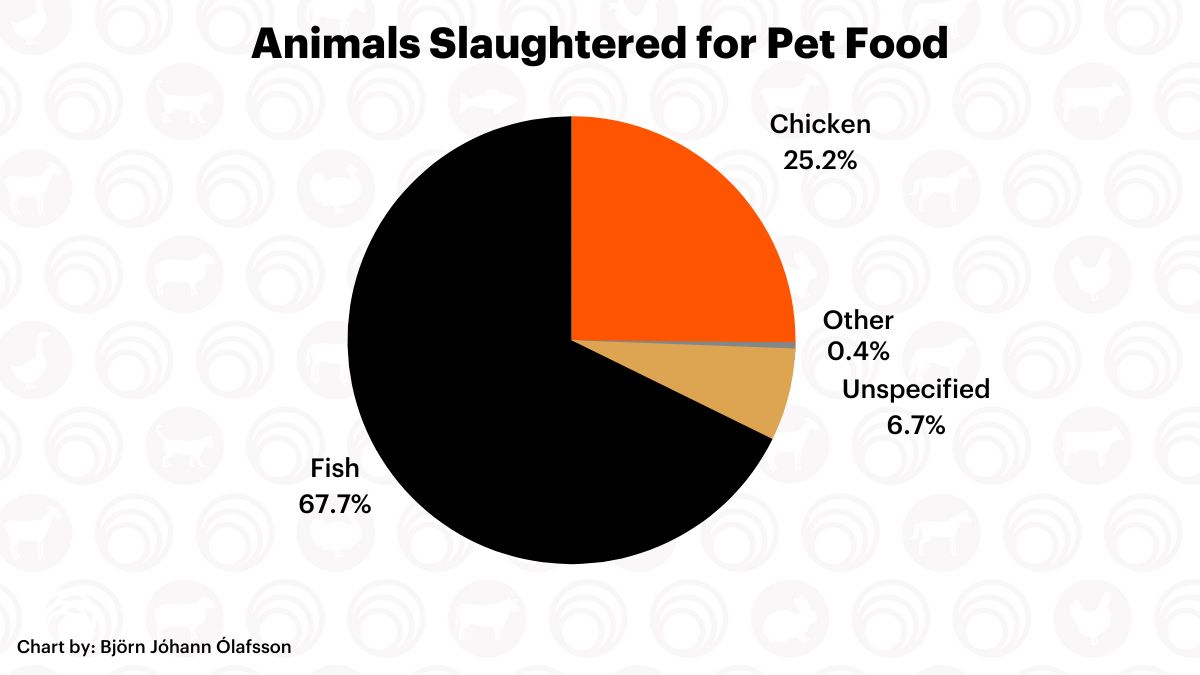

That’s quite a lot of animals, especially because pet food primarily uses chicken meat. Chickens are small animals who need to be killed in large amounts in order to meet demand. By using the 2020 Pet food analysis report and USDA slaughter statistics, we can approximate the numbers of animals killed to keep American pets alive.

Unsurprisingly, small animals like chicken and fish are killed in the largest amounts. While not every pet eats fish in their food, those who do require many animals to sustain them: over 2 billion for all U.S. pets. Nearly a billion chickens are slaughtered every year. A quarter-million unspecific species of animals are estimated killed every year as well. Larger animals, like cows, pigs, deer and turkeys contribute about 16 million lives collectively, too small a percentage to be visible on a graph.

Overall, each dog or cat fed an average diet will require the lives of just over 11 animal lives. If the animal eats fish, that number jumps to an average of 34.5 animals.

Right now, fish-based pet food is uncommon, but some pet owners may seek it out, especially for cats. However, fish is an unsustainable food for other reasons. The fishing industry is a massive plastic polluter and contributes to dangerous algae blooms that can harm biodiversity. In fact, nearly 90 percent of fish species are below their natural population sizes right now, largely because of industrial fishing. Fish-based pet food would contribute to these biodiversity crises.

Secondly, because fish and shellfish are so small, they need to be killed in extreme amounts to feed any animal. While fish make up only a small percentage of pets’ food now, they are slaughtered in the largest amounts by far.

Insect-based pet food has also emerged as an alternative, although it has yet to reach a substantial market in the USA. While there are some ecological benefits to insect-based food, such as the fact that insects can eat food scraps and require less land use, insect farming can lead to overharvesting and may offset natural biodiversity.

From a nutritional perspective, insect-based food can be suitable for dogs and cats, although researchers note that contamination and allergic reactions may be more likely with this diet.

Most evidence into dogs’ biology shows they do not need to eat meat to survive. Dogs are natural omnivores, meaning they can get their vital nutrients from either plant or animal sources.

Although the field is relatively new, nearly all research into vegan dogs shows they are as healthy as meat-eating dogs — sometimes healthier. One thesis from a Lithuanian veterinary academy shows that dogs eating a balanced vegan diet had fewer nutrient deficiencies than meat-eating dogs. Survey data in the UK shows that vegan dogs had fewer health conditions than omnivorous dogs. And a systematic review on the subject published in Veterinary Sciences argues that, while further research is needed, there is evidence of “benefits” on a vegan diet and “little evidence of adverse effects arising in dogs and cats on vegan diets.”

Some research actually indicates that dogs may live longer on a plant-based diet — although this research is correlational, it shows promise for extending pets’ lives with vegan products.

The idea of vegan diets for cats remains very controversial because cats are obligate carnivores, according to several veterinary associations and professionals. However, the research proving that cats need meat is thin, and these claims are often presented without evidence. While research on vegan diets in cats is nascent, the results are promising. One recent survey of over 1,000 cat parents (of both vegan and meat-eating cats) found that the vegan cats tended to need fewer vet visits, fewer medications, and suffered fewer illnesses overall. While the data are both correlational and self-reported, it does indicate the potential for meat-free and thriving cats. “Biologically, what cats need is not meat,” says the lead researcher, “but a specific set of nutrients.”

Some pet owners give their companion animals supplements to make sure they are getting every essential nutrient possible. While not strictly necessary (assuming the pet food is of high quality), pills containing Omega-3, vitamins E, C, Glucosamine and chondroitin can potentially benefit pets’ wellbeing.

Cultivated meat pet food — meat that is grown in bioreactors and has nearly the exact same composition as slaughtered meat — is generating waves as a possible successor to traditional pet food. Although it has yet to hit the market, multiple companies are developing sustainable cultivated products for our furry friends. These products may also end up being healthier, as the cultivation would be able to eliminate potential allergens and increase nutrient composition.

If we want to have a real conversation about climate impact and the ethics of agriculture, we need to also talk about kibble. The unsustainability of pet care is a growing problem, especially as the number of pets is increasing, and the meat sourced for pet food is increasingly less rendered.

This news might be hard to swallow for the hundreds of millions of pet parents out there, but there are a few ways to help. Only get a pet if you are fully committed to being a true care provider — something not everyone does. And there’s a lot of truth to that motto: adopt, don’t shop.

When considering your pet’s food, think about reducing or eliminating the meat in their diet. Make sure to use a trusted plant-based brand or follow a veterinarian guide to make sure your furry friend isn’t skipping out on any nutrients.