News

People Can Give Cows Tuberculosis, But We Rarely Look For It

Health•5 min read

Feature

Amid fears of a potential pandemic, researchers are busy preparing for the worst.

Words by Dawn Attride

Michigan State University’s Veterinary Diagnostic Lab has seen it all when it comes to testing animals for avian flu. Kimberly Dodd, dean of MSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine, jokes the lab has tested “everything that’s not human.” The increased spread of the latest strains of H5N1 avian flu are in part due to new mutations decimating scores of poultry flocks and dairy cattle around the country. Dodd and other experts are hard at work tracking the outbreaks — work that will be essential if scientists need to develop a vaccine. The U.S. already has an existing stockpile of vaccines from previous outbreaks, and these might offer some protection, but given the unusual spread of this virus, the race is on for scientists to develop a new vaccine that will be even more effective.

The emergence of the virus in animals from bobcats to pigs has worried experts keeping an eye on the next pandemic. So far, avian flu has killed one person in Louisiana — infecting 70 humans in total — but has not developed the mutations necessary to reach human-to-human transmission. Part of the critical work for these scientists is staying on top of the many outbreaks in hopes of honing in on each mutation.

Accurately predicting viral changes in real-time requires strong surveillance on a national level. It’s particularly crucial for avian flu, which is mainly spread by wild birds that can carry the virus long distances in a short amount of time.

Dodd’s lab is the sole lab in Michigan that carries out avian flu testing for the U.S. Department of Agriculture — so on any given day the lab is testing samples collected by state officials or from local farms to track how the virus is changing.

When the virus spread to dairy cows in March 2024, Dodd and her lab were on the hunt for answers. “Now we’re sort of in the stage of trying to understand the cattle who are infected — how long are they going to be protected for? Can they become infected again? And that’s a bit of a big question mark,” she tells Sentient.

To remain on top of avian flu, outbreaks need to be assessed holistically, experts say, where teams of scientists from different disciplines work collaboratively to curb the spread.

Until April 21, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s milk testing program was a way to provide continuous snapshots of the virus in cow herds across the country. With more than 1,000 herds infected so far, the work was critical. Yet since Sentient spoke with Dodd for this story, the testing program has been suspended.

Federal milk testing is just one of many food safety schemes that has been dismantled due to cuts driven by Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency. “I’m super proud of what we’ve done during this outbreak, but we would not have been able to do this if it weren’t the National Animal Health Laboratory network, right? So a lot of these cuts coming through to federal funds is really scary from that perspective,” Dodd tells Sentient.

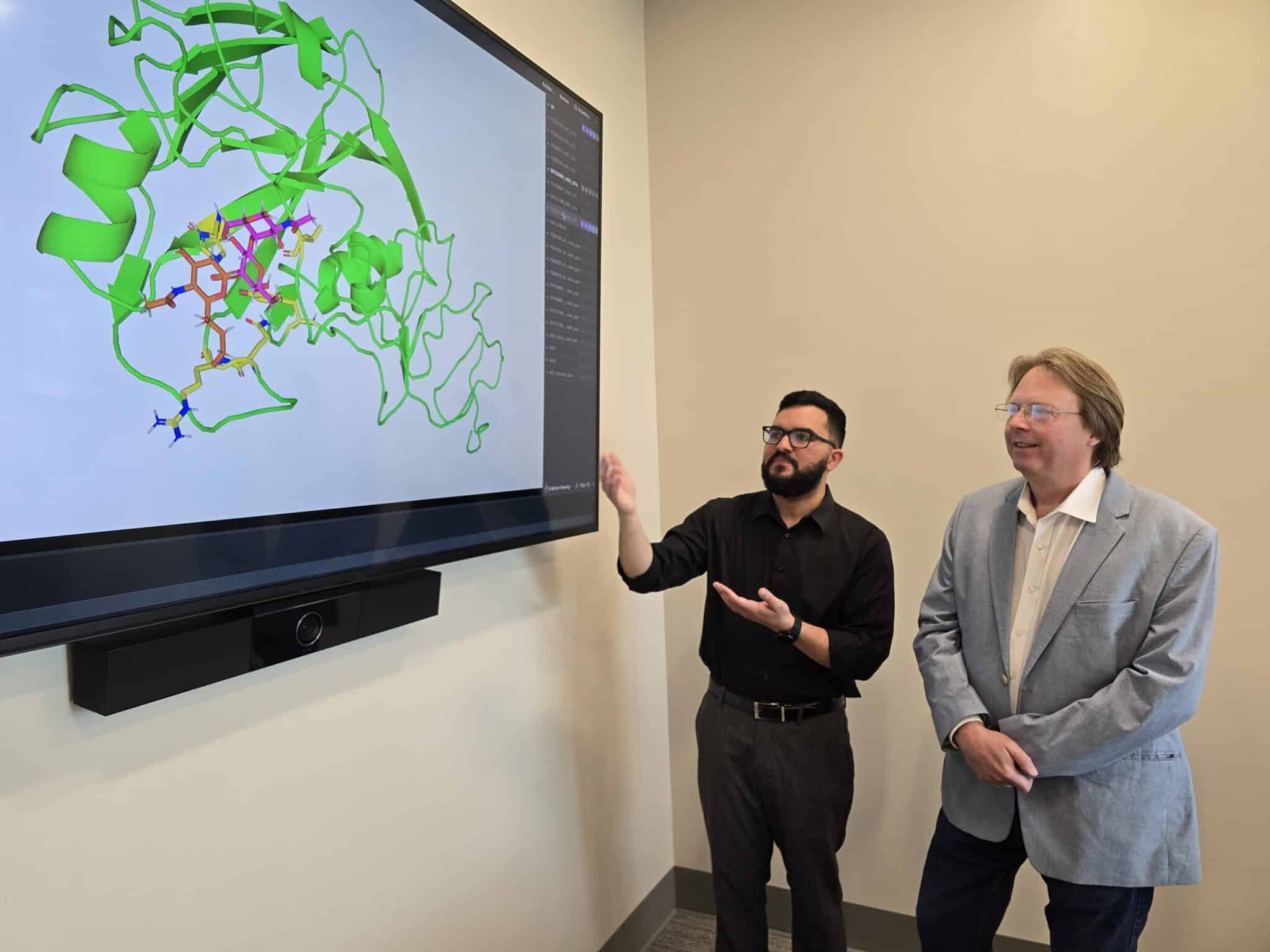

Image: Sayal Guirales Medrano and Daniel Janies of the CIPHER center at UNC Charlotte examine the structures and interactions of H5N1 viral proteins.

Down in North Carolina, Daniel Janies uses data from labs like Dodd’s to make predictions using computational modelling. On his screen, Janies compares potential viral mutations to existing immune defenses to see if there are any discrepancies that might signal alarm bells. The technology is rapid, too — “If you give me a new virus tomorrow, I could probably give you an answer in a day or two,” he says.

In a paper published last month, Janies, a distinguished professor of bioinformatics and genomics at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, found that current avian flu strains are evolving to escape mammalian immune responses. “These results indicate that the virus has potential to move from epidemic to pandemic status,” the researchers said.

Antibodies, which are immune proteins that fight infection, now have decreased binding ability for the more recent viral strains, which means a worrying possibility of spread among humans, according to the findings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Janies’ work was crucial to show that booster vaccines were indeed effective against new variants. With avian flu, Janies is looking at recent strains of H5N1 that have achieved promiscuity — a term that refers to the ability to infect all kinds of birds and mammals.

The researchers also zeroed in on a particular subunit of the virus called PB2 that hijacks the host’s cell when it infects. Mutations in this region of the virus, specifically in H5N1, bind mammalian and avian cells more effectively than this same part of the genetic material in previous viruses, Janies says.

“We see the virus evolving more efficiently once inside the cell,” he says, “and we even see its gains on those vaccine candidate strains from 2020 to 2024, in terms of this efficiency and promiscuity.” In short, this means that we need an updated vaccine, and fast.

If the situation escalates, there is a national reserve in the range of tens of millions of vaccines that might provide some effectiveness for bird flu. In a paper published in December, researchers at the U.S. National Institute on Allergy and Infectious Diseases found that existing vaccines neutralize the current circulating strains in lab tests. However, given Janie’s recent findings, these vaccines might not be enough.

So, what will the next vaccine need to be effective? It will likely be an mRNA vaccine, which as we’ve seen with the COVID-19 pandemic, can be tailored quickly to defend against new variants.

Drew Weissman at the University of Pennsylvania won the 2023 Nobel Prize for his work on the mRNA technology and has since been developing a similar vaccine against avian flu, which has so far shown to be protective in mice and ferrets. Moderna is also developing an mRNA vaccine, backed by a $766 million grant from the U.S. government, which will soon enter Phase 3 clinical trials.

There’s also the task of getting the public on board. A recent study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that nearly a third of people would be unwilling to take an avian flu vaccine if it were available.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., head of the Department of Health and Human Services, has a long history as a vaccine skeptic, which may play a role in amplifying vaccine hesitancy in the future. Public awareness of the virus’s impact also appears to be low — only around a quarter of people were aware the virus can spread from animals to humans, and over half were unaware that pasteurized milk is safer than raw milk.

Under the current administration, deep cuts to federal funding of science research and testing programs for avian flu could also hinder vaccine development. Despite these many challenges, the researchers tasked with testing and tracking avian flu are hoping their work is enough to stay one step ahead of the virus.